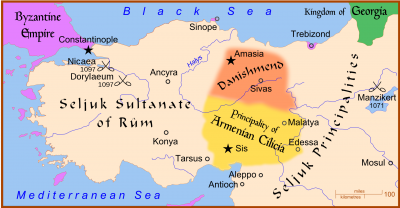

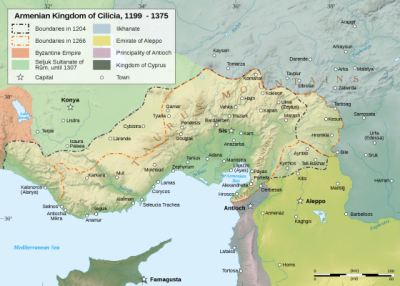

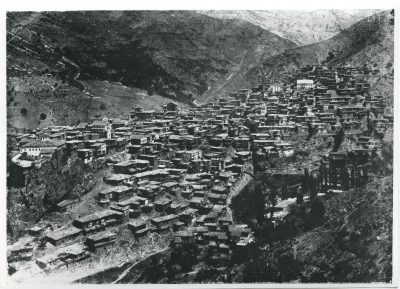

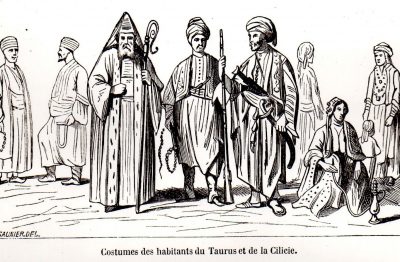

The Ottoman province of Adana corresponded roughly to the historical landscape of Cilicia (see also below). Cilicia or ‘New (Little) Armenia’ is a 50,000 square kilometer area between the Tauros, Anti-Tauros and Amanos Mountains. The region is divided into the mountainous Upper Cilicia in the west and the Lower Cilicia in the east, which lies only 150 to 200 meters above sea level and is the most fertile region of Asia Minor. In this climatically protected area, cotton, sesame and olive trees thrive in addition to citrus fruits.

The 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica described the province as rich in unexploited mineral wealth in the mountainous districts, and fertile in the coast-plain, which produced cotton, rice, cereals, sugar and fruit. The American Civil War that broke down in 1861, disturbed the cotton flow to Europe and directed European cotton traders to fertile Cilicia. The region became the centre of cotton trade and one of the most economically strong regions of the Empire within decades. Cilicia was noted for its agricultural production, including wheat, barley, oats, rice, seeds, opium, sugarcane and cotton. Cotton production became more popular before World War I. In 1912, the region produced 110,000 bales of cotton and 35,000 tons of cottonseed. Pyrite was mined in the region in the early 20th century.

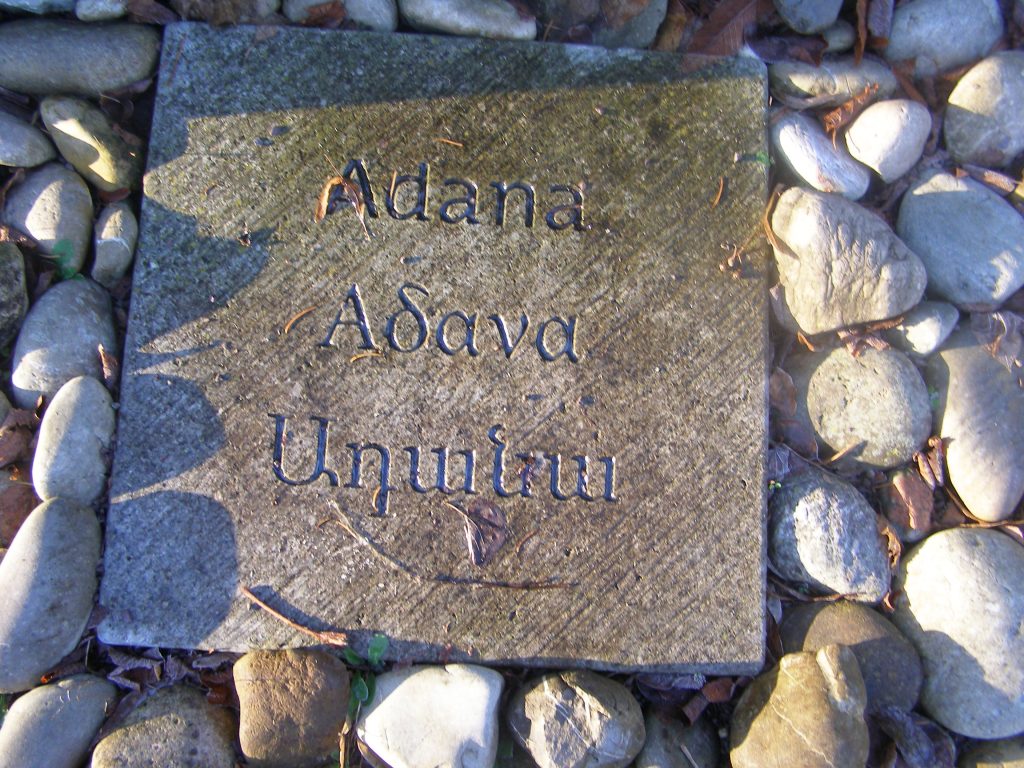

Toponym

With five millennia of settlement history, Adana is one of the oldest cities in the world. Its name, documented for four millennia, has remained unchanged since it was first mentioned in Hittite inscriptions. A possible derivation is from Adanyia, an area near Kizzuwatna in the Hittite Empire.

In Homer’s Illiad, the name of the city is mentioned as Adana. For a short while during the Hellenistic era, the city was known as Ἀντιόχεια τῆς Κιλικίας (Antiocheia in Cilicia) and as Ἀντιόχεια ἡ πρὸς Σάρον (Antiocheia on Saron). Under Armenian rule, the city was known as Ատանա (Atana) or Ադանա (Adana).

An ancient Greco-Roman legend mentions that the name of Adana originates from Adanus, the son of the Greek god Uranus, who founded the city next to the river with his brother. His brother’s name, Sarus, was given to the river (Seyhan today). An older legend, in Accadian, Sumerian, Babylonian, Assyrian and Hittite mythologies, originates the city’s name to the storm and rain god Adad who lived in the surrounding forests. There are Hittite manuscripts that were founded in the region regarding this legend. The legend had survived as the storm and rain god continued to create rain and abundance. The locals had great admiration towards the God and called the region Uru Adaniyya (Adana region) in his honor. The city inhabitants were called Danuna. It is also believed that this ethnonym is related to the Danaoi, the name for Greeks of the Trojan War in Homer and Thukydides.

Administration

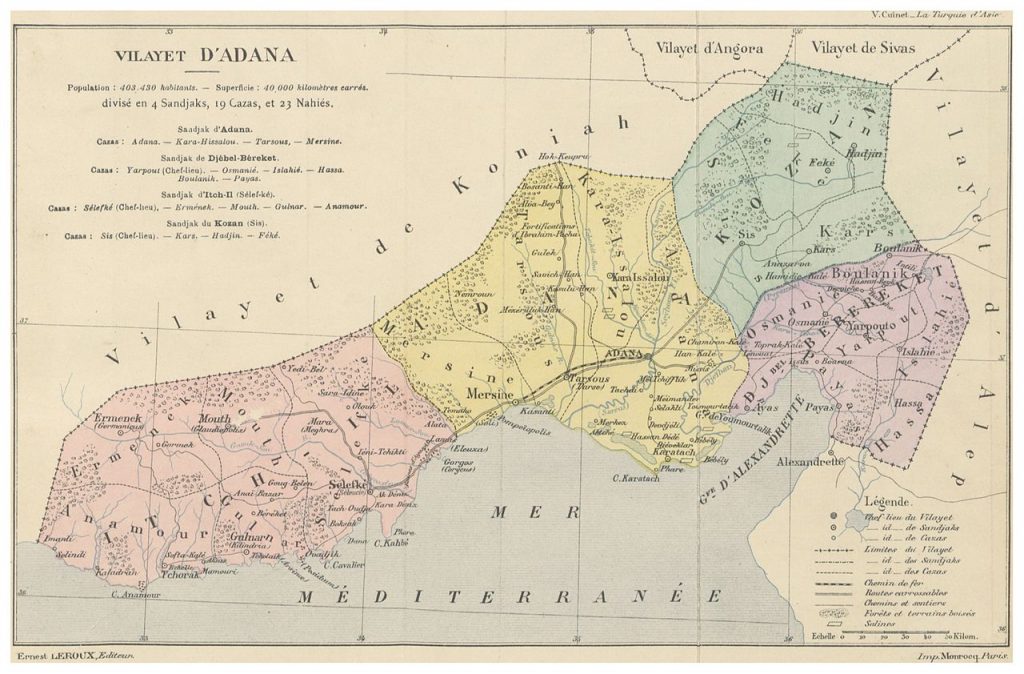

The Ottoman Adana Province was established in May 1869, succeeding the Adana Eyalet. At the beginning of the 20th century it reportedly covered an area of 37,540 square kilometers. The province comprised the five sancaks of Adana, Mersin, Cebel-i Bereket, Kozan (Sis), and Içil (mod. Içel), subdivided into 19 kazas.

Population

As a result of Byzantine and also Armenian population and settlement policies, the proportion of Armenians in the Cilician population grew from the 10th century onward. It was the goal of Byzantine policy to weaken the presence of Armenians in their original settlement area. For their resettlement, Armenian princes were rewarded with land ownership in non-Armenian regions. In particular T(h)oros I Rubenian (r. 1099-1129) encourged as ‘Lord of the Mountains’ immigration to Cilicia, driving out at the same time the Greeks from their strongholds of Anazarbos and Sis.

The preliminary results of the first Ottoman census of 1885 (published in 1908) gave the population of the province of Adana as 402,439.

Based on the official Ottoman data, the French geographer Vital Cuinet found that in the second half of the 19th century the total population of the province was 403,500, of which 169,089 were Christians (97,450 Armenians, 46,200 Greek Orthodox, 20,900 Syriac Orthodox, 4,539 Roman Catholics and Maronites).[1] Unlike most of the other provinces, the Armenian Apostolic Church data differed from the state census in that the Armenian data was lower than the state data in terms of the Armenian population: 79,600. Armenian clergyman Mesrob K. Krikorian explains this as follows: „The difference between the Turkish and Armenian statistics is caused, first, by the non-existence of an official or reliable census in the Ottoman Empire and second, in this particular case, by the fact that the Armenians did not intend to obtain any independence in Adana, and on the other hand the Turks were not concerned about any separatist movement.”[2]

The Armenian Apostolic Church in the Ottoman Empire was ecclesiastically and administratively divided into the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia (established 1062); the statistical data between the two institutions regarding the Armenian population in the province of Adana differed by almost 40,000: “According to the censuses, conducted by the Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia, more than 80,000 Armenians lived in the vilayet of Adana in 1913. They were settled in 70 towns and villages (…).”[3] The Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople gave the total Armenian population in the Adana vilayet in 1914 as 119,414; according to this source, they maintained 44 churches, 5 monasteries, and 63 schools with an enrolment of 5,834 students.[4]

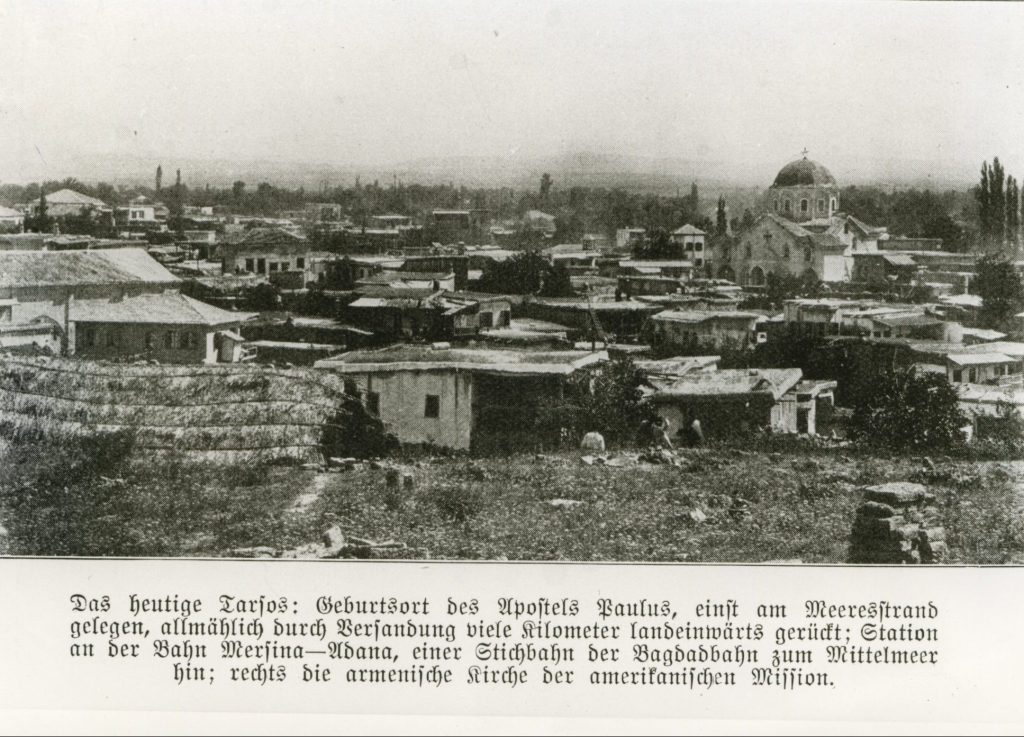

Today, and as a result of continuous persecution and destruction there reside Islamized Armenians in Zeytun, Maraş Tarsus and Adana.

The Trades and Professions of Armenians

“Some of the Armenian inhabitants of the province of Seyhan [Adana] were engaged in the cultivation of cereals and fruit and in cattle breeding. Their popular occupations, however, were the trades, crafts and professions. They were especially busy om commerce: in the manufacture of cloth, towels, handkerchiefs, bags, carpets, earthenware, and various silver adornments. They also laboured in tanning of leather, dye-works and painting., tinning, saddlery and stone-masonry. The Armenian traders and artisans were concentrated in the towns, and thus they presented the main industrial element. (…)

Many Armenians also specialized in different professions and arts, such as medicine, law, engineering, the postal and telegraphic service, and architecture. They were trained in the high schools and institutions of Tarsus, Antep, Istanbul, Beirut and Damascus.”[5]

Cilicia in Pre-Ottoman History

Bronze Age

From times immemorial, the two areas [of Upper and Lower Cilicia] belong together. In the second half of the the second millennium BCE, the entire region, known as Kizzuwatna, was part of the Hittite Empire. Contemporary sources mention the two main cities on the plains: the residence known as Tarša (Tarsus) and Adaniya (Adana). The most important language was Luwian. In those days, the region was ruled by a prince from the Hittite royal family, who was called “priest”.

Iron Age

After the fall of the Hittite Empire (after 1190 BCE), the two areas were included in a new, “Neo-Hittite” kingdom called Tarhuntassa, which had its capital somewhere in Pamphylia. It is not known how long this state existed. When the Assyrians discovered the region in the ninth century, they called the fertile eastern area Qu’e (with important towns in Karatepe and Adana), and the western area Hilakku (…).

The plains of Qu’e (also known as Awariku) were first conquered by the Assyrians. King Tiglath-pileser III (744-727) appointed a governor, whose residence was Adana. However, it was not a secure possession of the Assyrian empire: after the death of Sargon II in 705, it became independent again under the old dynasty, the house of Muksa. The ancestor of the Qu’ean royal family is known from Phoenician sources as Mpš, and can (according to an inscription from Karatepe) be identified with the Mopsus from Greek legend, who is said to have founded a town and an oracle in Cilicia. The Assyrian king Esarhaddon (680-669) reconquered the area.

Meanwhile, Hilakku remained independent. The Assyrians were not interested in the underdeveloped mountain area and its poor tribes. However, during the reign of Aššurbanipal (668-631 BCE), Hilakku was threatened by the Cimmerians, a nomadic tribe from the northeast that had already overrun Armenia. Therefore, Hilakku placed itself under Assyrian protection.

In 612 BCE, the Babylonians and Medes captured the Assyrian capital Nineveh (more). Hilakku survived the collapse of Assyria. A new kingdom came into being, in which both areas were united. Its capital was Tarsus. The Greeks rendered the title of its kings, suuannassai, as syennesis, and the name of the country as Cilicia.

The first syennesis we know about, is mentioned by the Greek researcher Herodotus of Halicarnassus (fifth century BCE). He tells that in 585, the syennesis and one Labynetus of Babylon (probably the future king Nabonidus) negotiated a peace treaty between king Alyattes of Lydia and Cyaxares, the leader of the Medes. The story confirms that Cilicia was at this time an independent power and did not belong to the Babylonian empire of king Nebuchadnezzar.

This syennesis was succeeded by one Appuašu, who withstood an invasion of the Babylonian army under king Neriglissar in 557/556 (ABC 6). It had been argued that Cilicia was invaded because it had become a protectorate of the Median empire, or may have appeared to have become a Median subject. We cannot know.

Persian period

It is certain that in 547/546, the Persian king Cyrus the Great campaigned in the countries west or north of the Tigris. Unfortunately, our source (the Chronicle of Nabonidus) contains a lacuna. It is not impossible (but unlikely) that Lydia is meant, where king Croesus was defeated. However, this may be, at some time in the 540s, Cyrus added Cilicia to the Achaemenid empire, making the syennesis (perhaps Appuwašu) a vassal king. Babylonian sources do not mention imported Cilician iron after 545, which strongly suggests that there were no trade contacts any more.

After the reign of a man named Oromedon, who is just a name, the next syennesis is better known. The Persian king Xerxes chose Cilicia to gather a large army to attack the Greek homeland (481 BCE). Next year, the syennesis served as one of the commanders in the Persian navy. He is known to have married his daughter to Pixodarus, a Carian leader.

At this stage, we begin to know a bit more about the way the Persians governed and used Cilicia. Its capital was Tarsus, where the loyal syennesis had its residence. We may assume that there was a Persian garrison. At several other places, we find military bases, mostly along the sea coast. The coastal plain often served to assemble armies. Although Cilicia had a native king, it had to pay tribute: 360 horses and 500 talents of silver, according to Herodotus.

During the Persian era, the fertile Cilician plains were the most important part of the satrapy. The relations between the inhabitants of the cities and those of the villages in the eastern mountains were sometimes less than friendly. After all, the people from the plains were sedentary agriculturalists and the mountain people were roaming herdsmen. It is certain that in the fourth century, the two groups sometimes came to blows, and we may assume that this was also true in the fifth century.

There were several important sanctuaries that remained more or less independent from Persian rule. One of the most important was that of a mother goddess that was called Artemis Perasia by the Greeks and Cybele by everybody else. Her shrine was at Castabala in the northeast. During the reign of king Artaxerxes II Mnemon, the Castabalans briefly revolted, but they were subdued by general Datames.

Another sanctuary was Mazaca, which must have been more to the Persians’ taste. Here, the sacred fire was worshipped. Another site of religious importance was the oracle at Mallus.

At the end of the fifth century, the third known and probably last syennesis was ruling Cilicia. He became involved in a civil war between Artaxerxes II and his brother Cyrus the Younger. When the latter approached the Cilician gate, the syennesis was forced to side with him. However, after the defeat of Cyrus at Cunaxa near Babylon, the syennesis’ position was difficult and he was dethroned. This marked the end of the independence of Cilicia. After 400, it became an ordinary satrapy.

One of its satraps was the Babylonian Mazaeus (361-336). His successor was expelled by the Macedonian king Alexander the Great, who conquered Cilicia in the summer of 333, and fell ill at Tarsus (text). After some time, he recovered and attacked the Cilicians of the Taurus mountains. This was probably a police action against the herdsmen. The new satrap of Cilicia, a man named Balacrus, was given special orders to attack the mountain people. Unfortunately, he was unable to overcome the herdsmen of Isaura, a tribal formation that now appear in history and was to play a role in the following centuries.

Hellenistic Period

After the death of Alexander in Babylon (11 June 323), Cilicia was first part of the kingdom of Antigonus Monophthalmus, who had been appointed as satrap of Phrygia. When he was defeated at Ipsus (301), Cilicia was divided by Ptolemy I Soter and Seleucus I Nicator, two former friends of Alexander. From now on, the coastal towns belonged to the Ptolemaic empire, and the interior became, after some confusion, part of the Seleucid empire. Twice, the region was contested: in the Second Syrian War (260-253), the Ptolemaeans gained ground, but in the Fifth Syrian War (202-195), king Antiochus III the Great captured several Cilician towns (e.g., Anemurium) and all of Cilicia became Seleucid. It remained so for a century, and was thoroughly hellenized. New cities were founded, and the old Luwian language was gradually superseded by Greek.

However, after c.110 B.C., the Seleucid power was waning, and the inhabitants of “rough Cilicia”, which had always retained some of their independence, started to behave as pirates. Although both the Seleucid and Roman authorities sometimes launched expeditions against the Cilician pirates, the two governments did not really care. After all, the pirates sold the slaves that the ancient economy could not do without.

It was only after 80 B.C., when it became clear to the Romans that the Seleucid empire was disintegrating and a power vacuum was growing, that the legions intervened. In 78-74, Publius Servilius Vatia subdued western Cilicia. To commemorate his victory, he received the surname Isauricus. Eastern Cilicia became part of the empire of Tigranes II the Great of Armenia. However, the Cilician pirates remained dangerous, until Pompey the Great attacked them. He settled them in towns and gave them land (67). This turned out to be an excellent settlement. The last Cilician war was conducted by Marcus Tullius Cicero (51-50), who defeated the last independent Cilicians.

Roman Period

During the next decade, the Romans were unable to establish their power, because they were involved in two civil wars, first between Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great (49-48) and then between on the one hand Caesar’s heirs Mark Antony and Octavian and on the other hand Caesar’s murderers Brutus and Cassius. When Octavian became sole ruler (after 30 BCE), Cilicia was finally pacified. Parts were given to vassal kings, and the remainder became an appendix to the province Syria. Although the governor of Syria sometimes had to fight against the mountain tribes (e.g., Lucius Vitellius in 36 CE), Cilicia was now a quiet part of the Roman world.

The emperor Vespasian reunited Cilicia in 72 CE. More than two centuries later, it was divided into two parts by Diocletian: the mountainous west became known as Isauria, and the plains retained the name Cilicia. In the late fourth or early fifth century, the remainder of Cilicia was again divided into two parts, simply called Cilicia I (Tarsus and environs) and Cilicia II (the eastern plains).

Late Antiquity

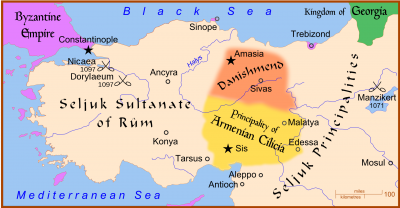

The fifth and sixth centuries saw great affluence, but in the seventh century, it became a border zone where the Byzantine Empire was defended against Arab incursions. About 700, the country became Muslim, but it became Byzantine again in 965. Many Armenians were settled in Cilicia, and the country became known as Lesser Armenia. During the Crusades, it became independent. In 1375, this last period of Cilician independence came to an end, when the country became part of the Ottoman empire.

Excerpted from: https://www.livius.org/articles/place/cilicia/

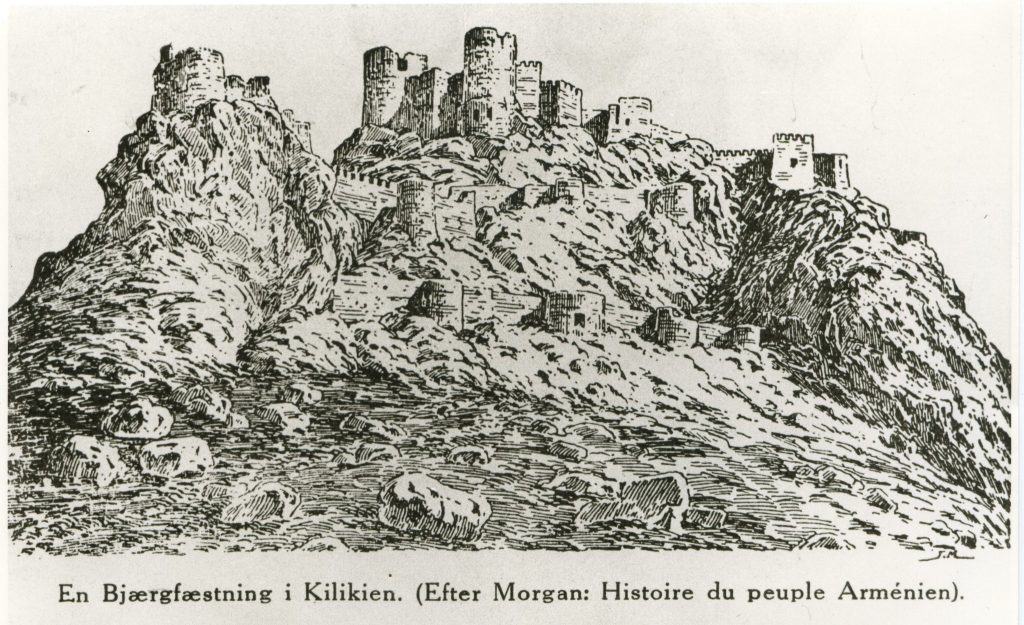

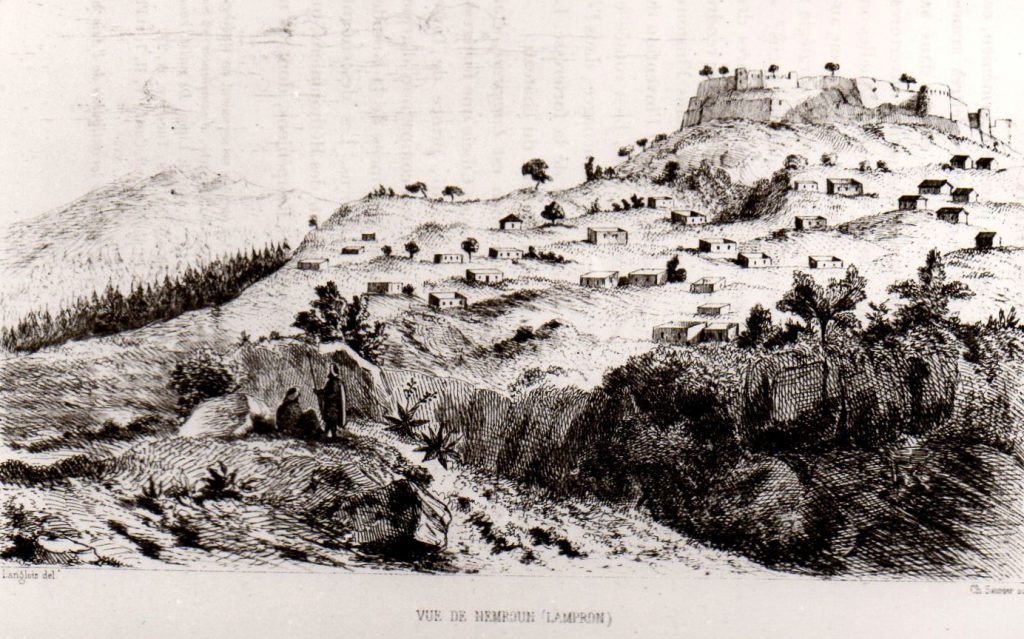

Under the protection of the Crusades: The Cilician Empire of the Rubenids

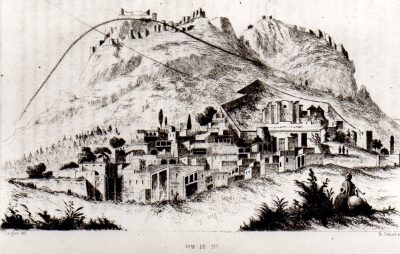

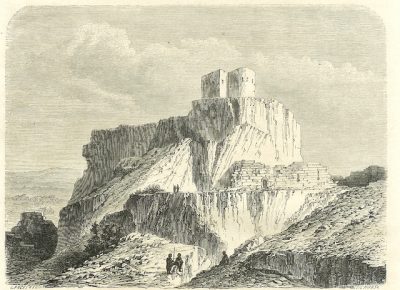

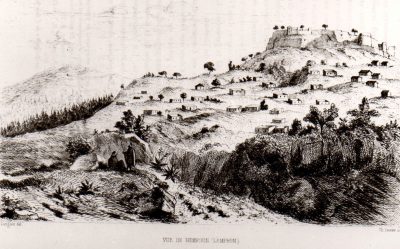

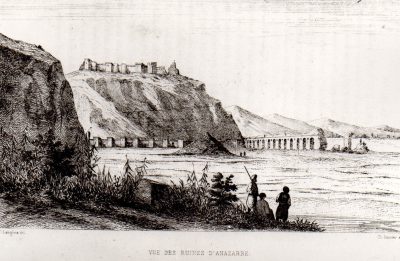

Since ancient times, especially since the reign of Tigran II in the first century B.C., Armenians lived in Cilicia alongside Jews, Syriacs and Greeks. Their number and importance must have been so great already in late antiquity that the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus (332 to c. 400) called the Bay of Alexandretta the “Armenian Gulf.” In the Middle Ages, the decline of the kingdoms in the Armenian Highlands massively increased Armenian immigration to Cilicia, where Filaret (Grk.: Philaretos), an Armenian vassal of the Byzantines and commander in their army, ruled from 1070 to 1090 but was unable to hold his own against the Seljuks. Prince Ruben, a relative of the last Bagratid king, Gagik II, who was assassinated by the Byzantines, took over Filaret’s short-lived state after establishing his own “barony” in 1080, which he and his descendants ruled from first from the originally Byzantine fortress of Vahka (Trk.: Feke), then from the Byzantine stronghold Anazarbos and the city of Sis. Traditionally anti-Byzantine, Rubenian (Rubenid) policy drew on the Crusader states that had emerged in the Middle East since the late 11th century, particularly the Flemish-ruled county of Edessa, the Norman princes of Antioch, and the Lusignans installed in Cyprus by Richard the Lionheart. Among the traditional enemies of the small Mediterranean state were the neighboring Asia Minor Seljuk Sultanate to the north (“Rum Seljuk”) and, to the south, the Ajubid state, against which a particularly dense network of fortresses, in which the rulers of Cilicia employed Knights Templar and Teutonic Knights, was supposed to protect.

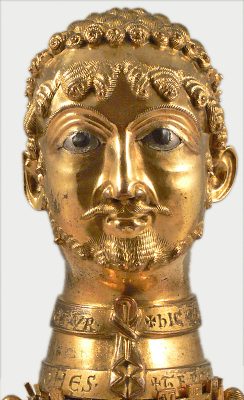

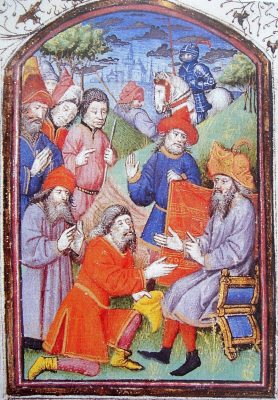

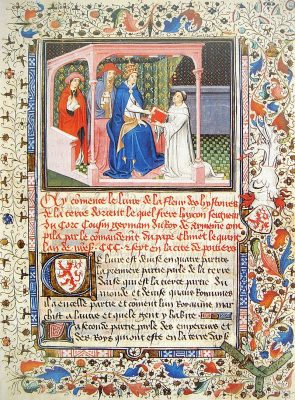

The Rubenid barons owed their rise to ‘kings of the Armenians’ to the Third Crusade (1189-1192) under the aged German and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (r. 1155-1190), who scored a brilliant victory over the Seljuks at Iconium (Konya) but drowned in the “Seleucid River,” the Kalykadnos, on 10 June 1190. For the services rendered by Prince Levon II Rubenian (as King Levon I, 1198-1219) rendered to the Crusaders in their passage through Cilicia, he was solemnly crowned on 6 January 1198 in the Cathedral of Tarsus by Archbishop Konrad Wittelsbach of Mainz, the legate of Pope Celestine III, on behalf of Emperor Henry VI; in return, of course, he had to recognize the German emperor as his overlord and the Roman pope as head of the Armenian Church. In his correspondence, the French king graciously referred to Levon as a “cousin from Armenia”. The Byzantine emperor did not miss the opportunity to send a crown, indirectly reminding him that Armenian rulers had been appointed by Roman emperors since the times of Trdat I. Contemporaries considered Levon’s rise as a rebirth of the Bagratid Empire, but the Cilician Empire surpassed its predecessor in pomp as well as pride and, unlike the Bagratid kings, minted its own coins. Even within the multi-ethnic Levant, which had always been a meeting place and a melting pot of cultures and religions, Cilicia was a cosmopolitan state where Armenian mixed with Byzantine and Arabic. Naturally, the “Frankish” or “Latin” crusader culture, from which most of the official titles at the Rubenian court were borrowed, became particularly influential. The crown council included the dzhansler (chancellor), who held the functions of secretary of state and foreign minister, the gundstabl-sparapet (connetable, lord of the crown), the maradshakht (marshal) as aide to the lord of the crown and royal treasurer, and the proximos (minister of finance). Following the Frankish model, the Rubenians had the lily in their coat of arms. Nobles now called themselves paron (baron), which in Modern Armenian became “lord”, chose Western European first names, and married members of the Crusader nobility, which in some cases led to conflictual dynastic claims to the Armenian throne. Latin and French became the court language, and the customs and ideals of Western European chivalry were followed. The willingness to adapt ended, however, when it came to questions of faith: Many of the paronayk, as always in contrast to the court, vehemently rejected the rapprochement with the Roman Catholic Church sought by the royal house. The Catholikoi, who had resided in the fortress of Hromkla since 1147 and in Sis since 1292, vacillated between harsh rejection and support for a union, to which Franciscan and Dominican friars also tried to urge the Oriental ‘schismatics’.

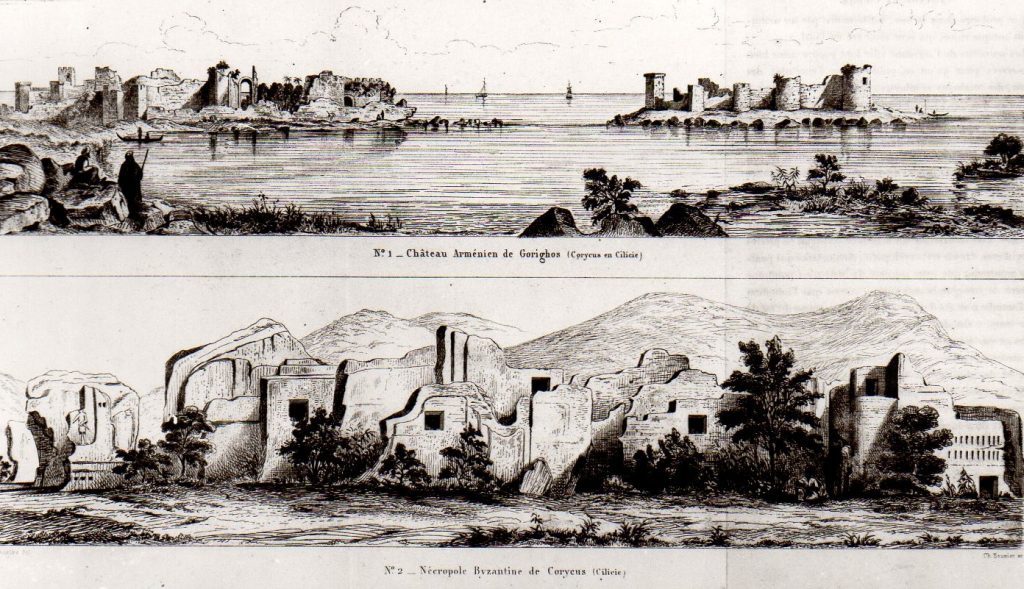

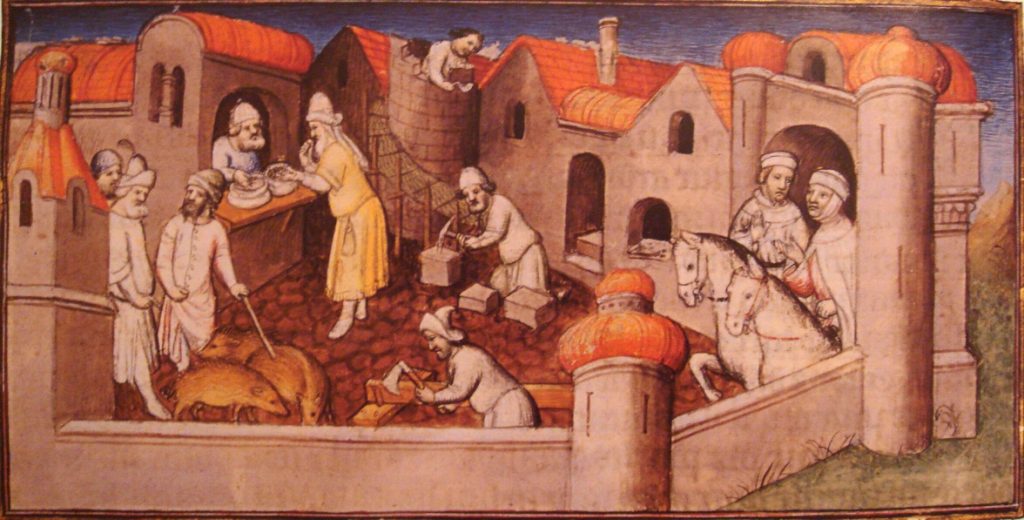

Cilicia’s wealth, which grew steadily until the 1360s, was based on trade, agriculture (cattle breeding, farming) and mineral resources: Gold, silver, copper, lead and, above all, iron were mined, smelted and processed, and the weapons produced in Cilicia were as much sought-after export items as the carpets. Cilicia formed an important link in the long-distance trade of the Near East with southern and western Europe as well as Persia, India and China. With almost Byzantine diplomatic skill, it opened its trading ports of Ayaş [Grk.: Aegeae; Italian: Laiazzo.; mod. Yumurtalık] and Korykos [ancient Grk.: Κώρυκος, Latin: Corycus; today: Kızkalesi] to the caravans of the neighboring Muslim emirates and at the same time secured transport contracts with the influential Italian city-states of Venice, Genoa and Pisa. FromAyaş in the west of the “Armenian Gulf”, Marco Polo traveled to the court of the Mongolian Grand Khan Möngke (Mangu) in Beijing in 1272, after William of Rubruk and Marco’s father Nicolò Polo had returned there from their long-distance journeys to Karakorum in 1255 and 1268, respectively.

Europe and was met with great interest because of its profound expertise, without, however, achieving the political goal of the author, a renewed Christian-Mongol alliance against Islam.

Such an alliance had only come about once before, in 1258, when a multinational force consisting of the Mongols who ruled Iran, Armenians from Cilicia and the South Caucasus, Georgians and the Normans from Antioch took Baghdad, then Aleppo and Damascus (1260), thus dealing a death blow to the Abbasid dynasty. But these were sham victories, for a new and stronger Muslim power had already emerged in the form of the Mam(e)lukes. These mercenaries, originally from the Black Sea region, had risen up against Saladin’s Kurdish dynasty in Egypt in 1257, conquered Frankish fortresses in Palestine, and in 1266 had driven the Mongols back as far as Tabris. One by one, the Levantine crusader states of Antioch (1268), Tripoli (1289), and Acre (1291) went down. Alone and isolated, Cilicia fell into increasing distress, especially when the Rum Seljuks also began attacking again from the 1320s. Appeals for help to the French king as well as to the pope merely aggravated the situation, as they were ineffective and only further irritated the Muslim opponents, and the union of the Armenian Apostolic Church with Rome, decided at the councils of Sis (1307) and Adana (1316), which was

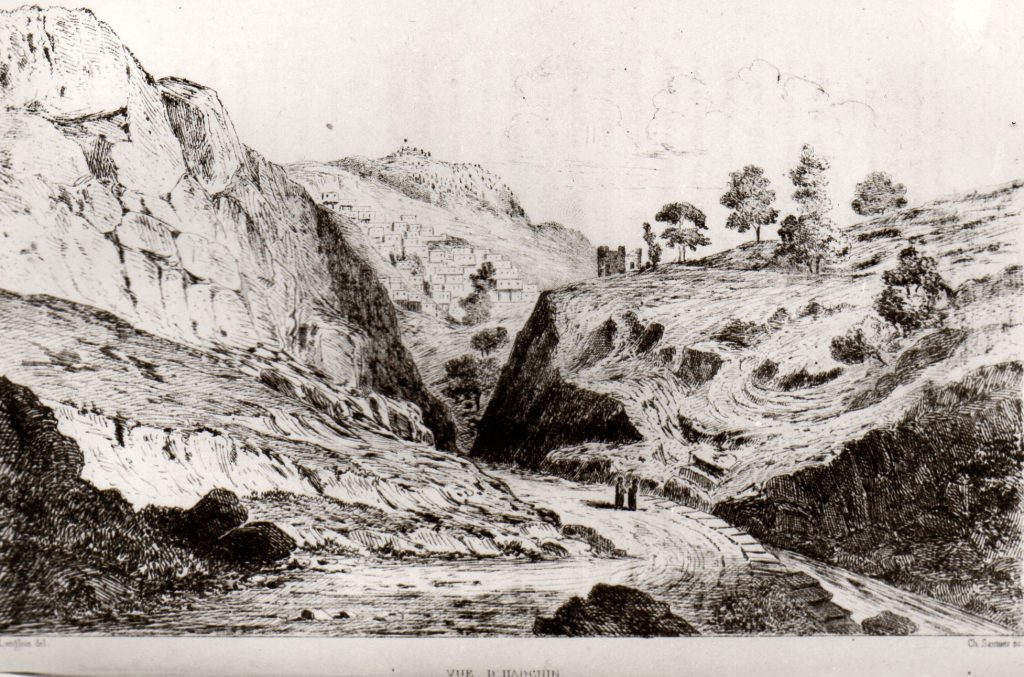

supposed to secure Cilicia the support of the “Latin” world, triggered an uprising of the nobility and the population and led to the internal division of society. In 1321, armies of Seljuks and Mam(e)lukes devastated the country, and King Levon V (1320-1341) had to conclude further, even more unfavorable agreements with the Mamelukes in 1323 and 1335, ceding to them the port of Ayaş and some coastal lands. With this ruler, the Hetumid dynasty ended in direct line, princes from the crusader dynasty of Lusignan took over the Armenian-Kilician throne from 1342. But already in 1359 the Mamelukes conquered Lower Cilicia. In 1375, after a three-month siege, the capital city of Sis fell, with King Levon VI going into captivity. When he was allowed to leave for France in 1382, he tried in vain to revive the crusading idea there. Meanwhile, Europe was preoccupied with the Hundred Years’ War. In 1383, Levon VI died in exile in Paris; his tomb, like all royal tombs, was desecrated during the French Revolution, and his mortal remains were scattered. Only his cenotaph, in the royal crypt of Saint Denis Cathedral, commemorates the last holder of the title ‘King of the Armenians,’ later claimed by the House of Savoy. In the rugged Upper Cilicia, the population and local rulers continued the partisan struggle against the Mamelukes for a long time. Settlements such as Zeytun (Armenian: Ulnia), Maraş and Hadjin (Armenian: Հաճն; mod. Saimbeyli) were able to maintain a de facto semi-autonomy as centers of resistance even during Ottoman rule from 1487 to 1920.

When in 1441 a synod decided to transfer the Catholicosate back from the Cilician capital of Sis, which had in the meantime been conquered by the Mamelukes, to the Eastern Armenian city of Echmiadzin, the incumbent at the time refused to move. This caused the ‘double-headedness’ of the Armenian Church, which continues to this day, with the Great House of Cilicia and the current incumbent Catholicos Aram I, whose seat has been in Antelias near Beirut since 1929, and the Catholicate of Echmiadzin with the Holy See at the place of origin of Armenian Christianity.

Excerpted and translated into English from: Hofmann, Tessa: Annäherung an Armenien: Geschichte und Kultur (Approach to Armenia: History and Culture). 2nd ed. Munich: Beck, 2006, pp. 48-53

Further Reading: https://armenian-history.com/cilician-armenia/

Under Mameluk and Ottoman Rule

“On the fall of the Armenian kingdom Adana with the surrounding country passed to the Mamelukes. In 1378 its governor was the Turkoman Yüregir-oglu Ramazan under the suzerainty of Egypt. The Ramazan-oglu dominated there for more than two centuries. In 1608 it became a directly governed Ottoman ‘eyalet’. From 1833 to 1840 Adana, together with Syria, was occupied by the Egyptians but was subsequently ceded again to the Ottomans.”(6)

Destruction

The Adana Massacres (April 1909)

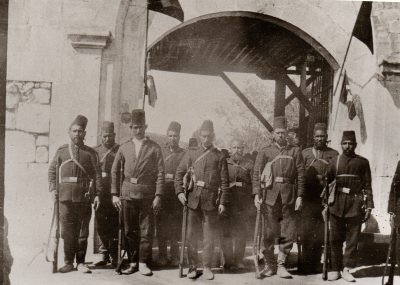

The massacres of the Christian population of the Adana and Aleppo provinces in the first half of April 1909 shattered the hopes of many Ottoman Christians, especially Armenians, that conditions would fundamentally improve under the new regime of the Committee for Unity and Progress (C.U.P.). Instead, the course of the massacres showed that the Ottoman forces that had been sent to settle the unrest in the province were soon involved in the massacres as well.

The first massacre in Adana had been decided in March 1909 at a consultation led by the provincial governor. Carried out with the help of the local authorities in early April 1909, 500 criminals had previously been recruited from the prisons to act as manslayers. The anti-Christian riots began in the city of Tarsus. Under the pretext of restoring order, the central Young Turk government moved Ottoman forces from the eastern Thracian province of Adrianople to Adana. But the appearance of the troops on 12 April 1909 ignited a second spurt of anti-Christian mass violence that surpassed in scope and brutality the previous massacres; the armed forces joined in the carnage.

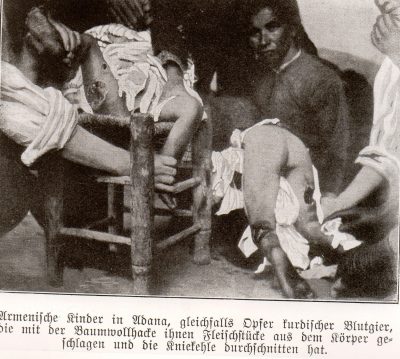

The traumatized survivors were predominantly women, children and the elderly. The highest casualty rate was among seasonal workers from Armenia, from where 40000-50000 people came to Cilicia annually at that time. The crimes found their echo in the Armenian and international press as the “Adana Massacres”. While from today’s perspective the continuity of the massacres under the rule of Sultan Abdülhamit II and the Young Turks is indisputable, for contemporaries this view still remained a matter of opinion. Many Armenians had hoped that the removal of the reactionary “Bloody Sultan” by the Young Turks would bring about an improvement in their situation and an end to despotism. However, a closer look revealed that both supporters of the Sultan’s regime and the Young Turks were equally involved in the Cilician massacres.

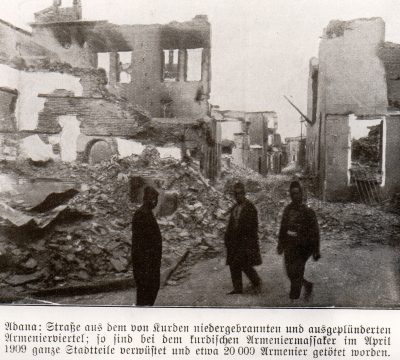

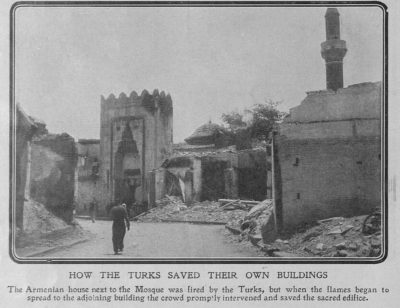

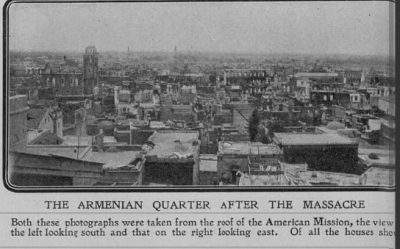

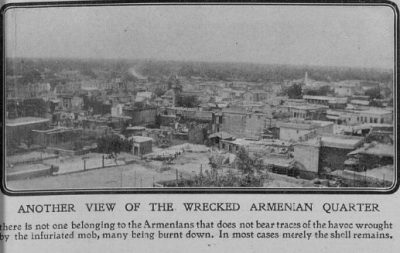

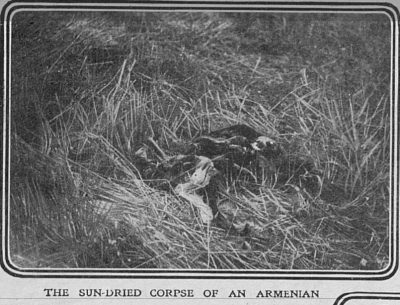

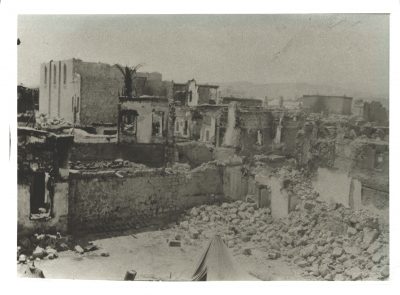

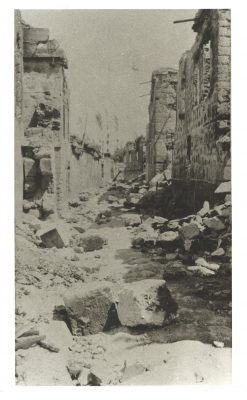

Massacres took place in all sancaks of the Adana and in the western part of Aleppo province, in several Armenian-populated areas in the north. About 30,000 unarmed Armenians were massacred, more than 20,000 of them in Adana province alone. Dozens of Armenian towns and villages were destroyed and set on fire.

According to an Ottoman government report, 2,093 Armenians, 133 Chaldeans, 418 Syrian Orthodox, and 63 Syriac Catholic people were killed in the Adana riots.[7] Estimates by foreign contemporaries were much higher. For example, U.S. Ambassador Henry Morgenthau Sr. estimated 35,000 victims: “A few months after the love feastings already described took place, one of the worst massacres took place at Adana, in which 35,000 people were destroyed.”[8] In addition to Armenians, the victims included Greek Orthodox, Syriac Orthodox and Syriac Uniate (Catholic) Christians.

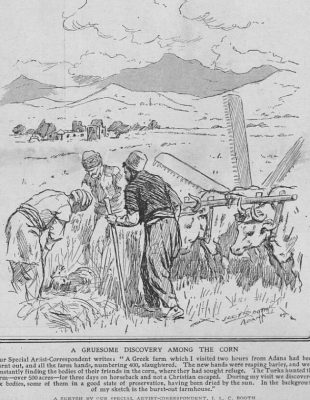

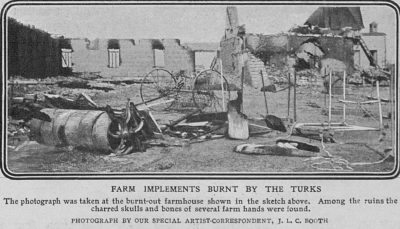

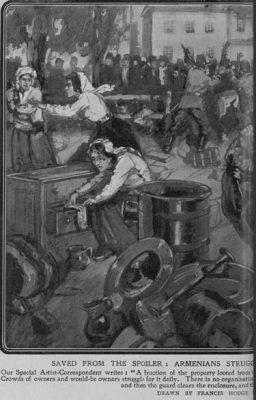

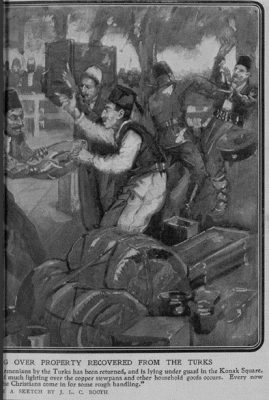

The ‘Adana Massacres’ were followed by a governmental inquiry, the findings of which were presented to the Ottoman Parliament and subsequently published in Armenian and French. The Ottoman government commissioned the Armenian deputy of Edirne, Hakob Papikian, to go to Adana, to investigate the situation on the spot and to prepare an official Turkish-language report for the Legislative Assembly. H. Papikian left for Adana, scrupulously investigated the events and noted in his detailed, posthumously published Report (1919) that “…not only did the number of victims exceed 30,000 Armenians, but it was an evident fact that the massacres had been organized with the knowledge and by order of the local authorities.” (Papikian 1919: p. 28; see also section ‘Anti-Christian Massacres’ below). In his account H. Papikian gave the number of non-Armenian victims as 850 Syriacs, 422 Chaldeans, and 250 Greeks.[9] However, and as evidenced by the report in the London journal The Graphic of 3 July 1909, the number of Greek Orthodox victims in the province of Adana turned out to be much higher (see the illustration of the massacre of 400 employees on a Greek farm in the right-hand column).

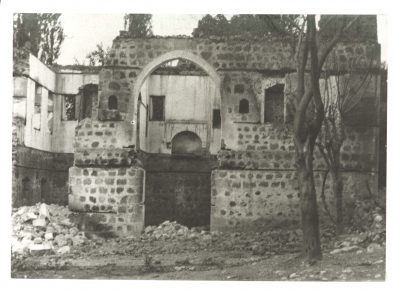

Adana: street from the Armenian quarter burned and plundered by Kurds; thus, in the Kurdish Armenian massacre in April 1909, entire neighborhoods were devastated and about 20,000 Armenians were killed.” (Source: Jäckh, Ernst: Der aufsteigende Halbmond. Berlin-Schöneberg, 1911; Archives: Center for Information and Documentation on Armenia / IDZA, Berlin)Even the German publicist and university professor Ernst Jäckh, who was an outspoken supporter of the C.U.P. regime, mentioned 20,000 victims in his work Der Aufsteigende Halbmond (‘The Rising Crescent’, 1911). However, he adopted the official version of the C.U.P., according to which Kurds were responsible for the “unrest” in Adana. In public executions, appropriately convicted Kurds were hanged:

Zapel Yesaian: In the Ruins (1909).

Yesaian’s reportage In the Ruins, published in 1911, contains the personal impressions, research, and

eyewitness accounts the author gathered in 1909 as a member of a delegation sent by the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate to Constantinople into the province of Adana. After massacres of the Christian population, Armenian orphans were to be located and arranged for help. However, since the possibilities of the delegation were extremely limited, this succeeded only for 500 orphans. Overwhelmed by the overall misery and her own impotence, Yesaian broke off her stay after two and a half months and returned to Constantinople to write – as a ‘means of survival’ to escape mental disruption and an over-identification with the victims.

The contemporary Armenian elite reacted differently to the mass murder of 1909: while the poets Siamanto and Daniel Varujan, for example, completely lost faith in the Young Turkish ‘revolutionaries’ and called on their readers to fight and resist, Yesaian, despite the mass extermination she documented, clung to the hope that the murdered would remain the last ‘victims for freedom’; however, she did not broach the issue of the Young Turks’ complicity in the crimes. As a truthful reporter, however, she did not conceal the doubts that her interlocutors in Cilicia harbored. She quotes a surviving widow as saying: “As long as we are in this country, we will remain their prisoners. Who can guarantee us that such things will not happen again?” Just five years later, the extermination of the Armenian and Syriac populations began almost nationwide.

The reprinting of Yesaian’s account by a Turkish publishing house in Istanbul, almost 100 years after its first publication, not only forms a belated tribute in the author’s hometown, but also testifies to current journalistic attempts to come to terms with modern Turkish history. The Armenian literary scholar Marc Nichanian regarded Yesaian’s reportage as one of the most important works in the Western Armenian language.

In the ruins (1911, excerpt)

When it had become very late, we declared the distribution of clothes and other relief supplies finished for the day. The stricken people gathered in the churchyard left in groups, according to their village communities, lamenting their hardships. Silently, we packed the relief supplies for the coming day, when a sharp, piercing voice startled us. Involuntarily, we stepped outside the door. A woman dressed in black and in tears stood before us, surrounded by other women who had suffered the same thing. Silently, they watched her. Not far away, leaning against the wall, a blind woman sang a lullaby. Who knows for which of her missing loved ones?

“His voice still echoes in my ears,” said the weeper. Overwhelmed by memories, she sank to the floor. For a while she could neither speak nor cry. She slapped her hands on her knees, and when her breath ran out, she bent her head back. Her neck stretched, and in a hoarse voice she cried, “O woe, o woe…”

One cannot imagine the extent of human misfortune. As she fixed her black eyes, filled with tears and pain, on us, we felt uneasy, seized by dizziness. One of our staff went to take her to the Prelacy’s reception room. When he took her hand to help her walk, the sad-filled woman trembled like a child with every step: “O woe, o woe…”

For a long time we heard nothing, because every time she tried to speak, her voice failed her with sobs. At times her eyes took on the confusion of a madwoman. We had her placed in an armchair, in a resting position, and we tried to soothe her pain. To calm the nervous twitches that her desire to speak had triggered, we left her alone for a while. A little later, stunned by her suffering, she fell asleep leaning on her arm. In her unusually pale face the half-lowered eyelids had turned blue, and through the opening the whites of the eye could be seen, and sometimes the pupil, motionless and pale as in a blind person.

Meanwhile night had fallen, and the light of a candle illuminated the room, though incompletely. The woman had awakened, and as her crisis had subsided, we now learned her horrible story:

Three days after Easter, my husband left the village. To buy wood, he went to Ziyamet with a Turk, Kel Musruh.[10] He was a farmer from our village. Towards evening, we learned from other farmers that my husband had been murdered by his companion. We cried, unaware of what else was written on our black foreheads. The next day, news of the riots reached us, but a friend of our family came and defended us, not allowing anyone to touch a hair on our heads until the evening. My daughters and my son, 18 years old, sat with me and reminded each other all the things their father had planned for the winter. O woe, how did he die? From what weapon? We didn’t know. We were as pale as the wall. And when my daughter rose, she looked like a banshee.

In a distance we could hear the thunder of firearms. Outside, the dogs were howling, and when they came near an entrance door, their muzzles were open, and they howled for hours. The Turk who was supporting us got confused. Some came from outside, they talked to each other, whispered and soon went on their way, with dirty hands, twisted eyes and foaming at the mouth. Shortly before daybreak, the befriended Turk left us, whether out of fear or on someone else’s orders I don’t know exactly.

A little later they came. Oh horror… everything was looted. When the house and the store were completely empty, the owner appeared, locked the store door, sealed it and took all the documents with him.

We were left alone and in an inconsolable state, but soon realized that our suffering was not yet over.

My main concern was not the loss of goods, but the children. I did not know for whom I should weep more. Towards evening, the village chief, Aghze Ganle Mehmet Ağa, came and tried to convince us to seek refuge in his house. My home now lay in ruins, my heart burned as if by fire… My husband had been murdered, I was left all alone in this world… here I had lived, here I was happy: “I will not leave the threshold of my house, I am ready to die here. Leave us here!”

For a while he remained silent. He was hesitant, soon taking in my son, soon my daughters. He had experienced how my children, playing with his children and grandchildren, had grown up. I could tell he was moved inside. His breath came in gasps, and sweat broke out on his forehead. “Alas, alas,” he said at last, “the day we were born must have been cursed. Pain is written on our foreheads. And we burn, you with one pain, and we with the other pain…”

Then he approached me and whispered in my ear, “From the gatherings out there, I know for sure: they will slaughter you all! I want to take you to my home! You can come or stay here. The choice is yours!”

I threw myself at his feet screaming, “I have lived my life, my hair has turned white. It is not for my sake that I beg you, but for the sake of the children. You are my brother, my supporter. Since there is no other way out, let your will be done!”

So, together with my children, I went to the house of the village chief.

We were led into a room from which the chief’s family was retreating: the women were frightened and fled screaming when they saw us, as if we were dead men risen from the dead. There we sat side by side and wept. My hand was on my son’s head, I was stroking my children, one by one. I held my son, my Karapet, close to me. I could only see him in a blur because of my tears. My longing parched my throat like thirst, my mouth, my love… At that moment I had almost forgotten my husband. When my children asked: “Mother, we are safe here, why are you crying?”, I replied: “Because of your father”. Then my children raised their voices, and together we looked at my Karapet. Pale as death, with trembling hands and legs, he walked up and down the room, came and sat down opposite us.

Shortly after we entered the village chief’s house, our Turkish neighbor appeared and reported, “Bad, very bad, the news is bad… Burning everywhere, destruction, no more Armenians, no more churches… the Armenian people have been destroyed, their roots uprooted.”

He stayed a little longer, moving his head back and forth, and spoke, “If you convert to Islam, you will be saved. Otherwise, you will be killed, that much is clear!”

My elder daughter and I replied in one voice, “Let it be so… since everyone is dead, we too will die. We have been destined for a short life, more of which would not be allowed!”

The Turk cradled his head and repeated, “It is clear that you will be slaughtered!” Karapet, who had been leaning against the wall, turned yellow as wax, even the flesh on his face trembled. Slowly he came toward us, and with each step his whole body shook. As if he had forgotten how to walk and talk, he opened and closed his mouth a few times, but no voice came out.

When he came to us, he embraced my knees, looked at me, then at his sisters, and pleaded: “I am not yet eighteen years old and have not yet lived! Have mercy on me! I want to live, live I want… Let us embrace Islam, what harm if we convert to Islam to live! Mother, I don’t want to die!”

At first my daughters and I refused and rebuked him, “Living this way is worse than death. Shame on you! The way your father went, we will continue. Our blood is not redder!”

“Mother, I want to live! Live! Live!”

The Turk was still standing beside us, and every now and then he repeated, “It has been decided to slaughter you!”

Finally, I could no longer bear my son’s pleading, and to save his life, we embraced Islam.

Shortly after that, the chief arrived. His eyes slid indecisively over my daughters and son. He acted as if he had pity, making an effort to appear cheerful: “It has filled my heart with joy that we are now fraternized in the same religion. This makes you holy to us… May the cloud of pain and sorrow be passed over your heads!”

For a while he looked at the Karapet, frozen and pained, then suddenly he reflected and directed his gaze to the ground. For a while we were all silent.

“Bad, bad,” he then raised his voice like the other Turk. “You have converted to Islam and saved your necks from the noose. But it could happen that you are not believed and the authenticity of your faith is doubted… the coming hours are full of sorrow and suffering… I saw the mob like a sea stirred by the storm. They ran through fire and blood, and their bodies and clothes were smeared with blood.”

“Who? What?” I asked, startled.

The village chief looked me in the eye and said mysteriously, “The mob!”

Then he suggested that I marry my two daughters to Turks in order to inspire confidence among former enemies.

Maral jumped up and cried like a wolf: “Such a thing shall never happen and will not happen! Have you no heart? Are you not human? Have you experienced no suffering, no pain in your lives? Your heart has never had compassion for your children? How dare you make such a proposal to me on such a day of pain?”

They reassured me and said that the marriage was a mere formality, and that my daughters – the younger one was just twelve years old – would stay with me for another two or three months, and then we would see what happened next. On this assurance, my daughters were married.

We spent the night, that black night, crying and in mourning, with doubt in our hearts and full of fear. The next day, Mustafa the barber, who had been a professional rival of my husband Karapet, had notified a worker of Khadir Efendi that the village chief had taken in Armenians in his house. Shortly thereafter, unrest arose in the village. We did not know anything for sure, but listened for the noise outside. Was it the noise before the storm? Was it dogs howling or human noise? Or all of them together? Suddenly we heard gunshots, then silence, then storm again. People screaming like wild animals, more rifle shots, then a little silence.

I rose, opened the door of the room and waited. A Turkish woman who was part of the household came over. “For the love of God, what’s going on out there?” I asked her. She covered her face with a dark red headscarf and I could not recognize her. At first she didn’t want to answer and walked past, but then stopped, looked at me and was silent for a while. There were flashes from her eyes, although the opening for the face was in semi-darkness. From the red headscarf I saw her eyes flashing:

“Pigs, Gavurs[11],” she finally said. “Because of you, the peace of our house is violated. Our food and sleep have been desecrated. Like dogs, you have become rabid. Who told you to revolt? With flags in your hands and armed, you stormed into the village to trample it… Where are your fidayins[12] now ? Where are your supporters from the ‘Freedom’ Party Hürriyet ve İtilaf[13]? May the Freedom Party go blind in both eyes, since it has driven you out of your minds!”

Breathing heavily for a while, and still incensed, she continued, “What then was the fault of our Sultan Abdülhamit? What bad thing did he do that they expelled him and put the Freedom Party Hürriyet in his place? Your Gavur-Hürriyet!”

I tried to answer her, but that upset her even more. Almost shouting, she added, “Because Hürriyet is not Islam, can never be Islam!”

An indescribable noise interrupted our conversation. I couldn’t tell if she was laughing or continuing to rant, but her eyes sparkled under her headscarf, “Damn people! Wherever you appear, you bring sorrow and suffering. They have come to burn down our house just because of you! Your evil existence, when will you leave us? Go away from here, seek refuge elsewhere, and don’t put more people in danger!”

Weary and weak, silent and silenced I cried. Finally, the Turkish woman left, complaining and scolding. In the meantime, Aghze Ganli had sent word for me and my Karapet to come to the Turkish house next door, to the man who had asked us to accept Islam. I was to leave my two small “married” daughters with their families.

The mob had reached the threshold of the house where we had taken refuge. Through the fanlight we could sometimes see black arms and barrels of firearms. The mob roared like rabid animals.

Crawling through the back door, I went with my son to the Turkish house next door. My daughters, hiding under a mat, stayed behind. Later I learned that the murderers had discovered them there and dragged them outside to kill them. But all at once one of the mob shouted, “We should not kill the women. Also the old, the blind, the severely handicapped, let them live! The rest take with you!” And because they had heard that my two daughters were “married,” they were taken back to the house of the village chief.

Then the crowd flooded toward the house where we were hiding and besieged it, threatening the inhabitants that they would burn the house down if they did not hand over the gavurs.

After that, the Turkish women of the house came to us angrily, with angry eyes, and dragged us out. On the doorstep I stood between two swords. My Karapet was as pale as a dead man and unable to hold himself upright. I covered him with my body and shouted, “First you must kill me!”

A black, scrawny face almost touched mine and laughingly said, “There is no order to kill the women! Get lost!”

Then I heard a sound like snoring, as if someone was suffocating. I turned around as… how did I get over that moment… Someone grabbed Karapet’s arm and pulled him. And he resisted. He was pushed to the ground, but managed to free himself from the murderer. In a voice that was strange to me, he shouted, “I am a Muslim! In honor of the Prophet, let me live!”

My son looked at me without recognizing me. He looked at the crowd, looked at the one who had dragged him to the ground, and moved his mouth to say something else. His breathing was so heavy that it could be heard from far away.

“Well, well,” many answered him, “let’s get you circumcised!”

A few people attacked him at the same time and dragged him away. My son sat down again. His clothes were torn, his knees cracked as they dragged him across the ground. On the ground were the traces of his blood.

Screaming, he tried to turn back: “Mother, they want to kill me! Mother, I don’t want to die! I don’t want to die!”

Oh my God! Since then there is not a moment when I do not hear this voice and Karapet’s pale face does not appear before my eyes, because his voice is caught in my ears. His death throes have been imprinted on my eyes.

I ran after him, but did not reach him. I ran back and forth… It seemed to me that everywhere I heard my son’s voice, and so I lost my way, lost my way. After a while, Mrs. Safiye came to me, the sister of Aghze Ganli, grabbed my hand and led me to her home.

“It behooves you to stay with your daughters!”

“And my Karapet?” I asked, almost choked by my tears.

“God’s mercy is great,” she answered, “he did not suffer much!”

I had been expecting the news of my son’s death, but I didn’t want to believe what I was hearing. Petrified with pain, I stopped in front of Mrs. Safiye.

“Sit down,” she said in a saddened voice, taking my hand and forcing me to sit down on the grass where she told me everything. “I was there, I saw everything with my eyes and heard everything. People were like drunk, insane, the son ready to kill his father and the brother to kill the brother. God has ordained such evil moments for us. And to such a moment your son fell a victim!”

“My boy, my boy!” I exclaim. “Your sun went out! Life was so sweet to you. With which weapon did they kill thee? Where were you hit? Where did your wounded body go? Would that I could give you life for the second time! Take light from the light of my eyes, breath from my breath and look around you! Get your fill of life, my boy! How did they kill you?”

“He was taken to the riverside,” Safiye answered, “and there Habib met Karapet: ‘Born on the same earth, lived under the same sky – Habib, between us there is the law of salt and bread! From the same vessel we ate, from the same cup we drank! Spare my youth! ‘ But they did not listen to him and tied his hands. Habib pulled the knife from his belt and stepped closer… ‘I am afraid of the knife! Throw me into the river! ‘ Karapet said for the last time. But Habib approached smiling and plunged the knife to the hilt into his friend’s neck. Then they threw him into the river… The crowd watched as twice the bloody body floated to the surface and then was carried away by the water current. Resulunoğlu Khedir shouted that the river water reddened where the body of the gavur floated along. ‘Perhaps he is still alive?’ The third time Karapet’s body floated to the surface, he shot at him.”

“The world went black for me, Safiye,” I told the Turkish woman, weeping. “All the flashes of God’s wrath are not able to punish your crimes. What day will bring your repentance? You will drown in the tears of mothers, widows and orphans!”

The more I talked, the paler Safiye became. Trembling, she took my hand and tried to comfort me, “Don’t cry, don’t cry! He was not tormented much! Thank you Allah, he proved to be merciful to you, because how many killed there are who were tortured! What is not told… There is Armenian blood under everyone’s nail!”

She took me to her brother’s house, where my two daughters were also. Reunited, we cried, but they would not leave us alone. The women of the house and the neighbors were around us. Some mocked our suffering, “Where is Hürriyet now?” Some showed compassion, but the rest reproached us, “You are not crying because of your father or son, but your tears are for your millet, your nation of faith! In each of your tears there is curse and poison for us…”

Half an hour later the Turkish women came and declared that they had to take the brides away.

“Leave us alone!” I exclaimed, “I have no more strength to argue with you! Let us weep for our losses!”

Realizing that no one was listening to me, I turned to the village chief and reminded him of his promise. But he replied that there was nothing he could do. Together with the Turkish women, gunmen had come to take my daughters away by force, so I was compelled to comply.

A month passed. My husband and son had been murdered, my two daughters kidnapped, my house looted empty. I no longer possessed any hope in this world, when one day a policeman came by and announced that he would accompany me to the military tribunal if I wished to file a complaint.

The first time, in the face of threats, I told him verbally that I had no complaint, but after a while I did see some hope of punishing the criminals and freeing my daughters. So I found ways and means to send a message about my situation to the delegation of the Armenian Patriarchate based in Adana. Two weeks later, a policeman came to see me again. There was talk that some Turkish criminals had been hanged and many more were full of fear of prosecution. I was allowed to come to Adana under police escort.

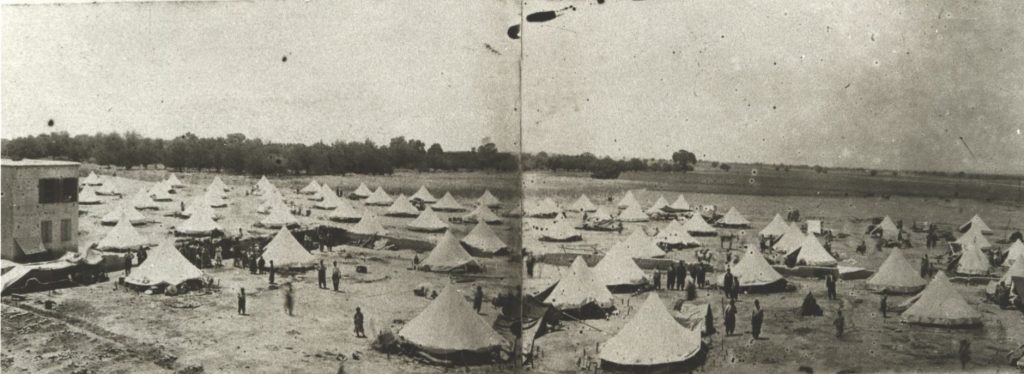

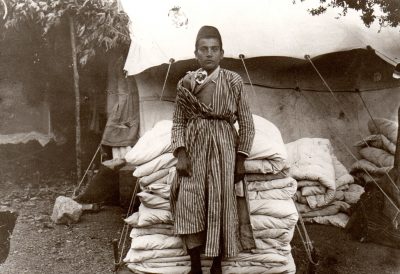

It had until then appeared to me that there was no woman more unfortunate than me, but when I was in Adana I heard thousands of similar stories. I suppressed the sorrow in my heart and submitted a request to the military court three times. But my three petitions remained unanswered. Today I was at the place where the tents for homeless Armenians are set up, and there I also met a Turk from our town.

“I have been looking for you,” he explained courteously, “the husband of your youngest daughter sends word that your accusation is useless. He has heard that you have brought charges against him, as well as against the murderers of Karapet and your husband. But all this is in vain. Look, we are all still on the loose and moving freely.”

I felt sick. Immediately I ran to the military court. My anger was such that none of the bailiffs at the court entrance could restrain me. When I entered the courtroom, everyone was busy and wanted to turn me away, but I spoke loudly about all my sufferings, about everything I had experienced. I suffered a dizzy spell in between, but they didn’t notice because I kept telling.

I told them how my son was dragged back and forth on the floor and how they plunged the knife into his neck, I told them how cruel the women were, how hard-hearted the men were. And further I said how my mother’s heart was stabbed, and how they laugh at me today, sending me the message that I should not hope for my petition and the military tribunal, because all this is a hoax and irrelevant. And behold, the perpetrators move freely, and so it will be until the end.

When I had finished, it had become quiet in the hall. I thought no one was there anymore, I was alone. But when I woke up, I found that the staff members who had been sitting there behind the table listening to me were petrified with excitement.

Finally, one began to speak, “The dead do not come back to life. You, woman, find comfort in your children who are still alive… Calamity passes like an evil storm after causing destruction… You must be able to forget the past…”

“The past? The past is my son killed, is my husband slaughtered, my daughters stolen! The past is inscribed in my heart with letters of fire!” One of the military men looked at me intently and wiped the tear track from the corner of his eye with a small pencil. His lips were white, and as his excitement increased, he looked into the notebook opened before him as if he were reading.

“You are young and on the threshold of life! Consider, after all, why I was deprived of my son. Living in this world has become a great burden for me. I hope to find my peace with death. What I have seen and heard is enough to poison the lives of a hundred mothers. I no longer possess any hope. But I have come here to tell you: be just and punish the criminals!”

“What is done is done! Whom shall we punish? Enough blood has been shed. Forget the past!”

They whispered among themselves, and one of them asked me, “Who looted the goods from your store? Who took the inventory of goods? What amount of money do you still have to get in the village? The military court will do everything necessary to make up for the material damage!”

“I did not come here to get back the looted household items and the inventory of the store. I came here so that the guilty parties would be punished!”

“Before the disaster, we were siblings! Forget about the incident. From now on, we will live like siblings again. Retaliation causes enmity, and peace in this country will not be restored. Also, it will be a good example if you love your enemies as your religion dictates!”

Realizing that they had already forgotten the meaning of my narration and were becoming impatient, I took out my veil and said, “Since you do not want our lawsuit to be litigated, may God judge you. You and your future generations shall be cursed!”

The hall spun around me, the sound of chairs being moved made me fall silent. They rose, and then they sat down again. And at that moment it seemed to me that the whole world heard my voice:

Hakob Papikian: Anti-Christian Massacres

The Ottoman Armenian Member of Parliament for Edirne (Adrianople), as a member of the Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry, wrote a report on the results of his investigation in Adana. However, one day before he could publish it, H. Papikian passed away in rather suspicious circumstances on 1 August 1909. It was not until ten years later that his report could be published posthumously in Constantinople. His report was more critical than that of Zapel Yesaian. About the non-Armenian victims of the Adana massacres he wrote:

“I have proved that there are significant differences between official and non-official data regarding the number of victims. Armenian and foreign journalists agree that the number of victims varies between 25,000 and 30,000. Official figures put the number of non-Muslim victims at 1,500 and the number of Muslim victims at 1,900, but recent investigations by the authorities put the total number of victims at 6,000. The official figures are based on information provided by the municipality as well as by headmen and clergymen of some villages. Needless to say, the city authorities are not known to be credible sources and are known to be inaccurate. Thus, the authorities in Adana did everything to minimize the number of Christian casualties. In addition, in many places the clergy and village leaders were among those killed, such as in Hamidiye, where seven people were hiding. Seven to eight persons also found refuge in the French factory of M. Sabatier, but the remaining 2,000 people were murdered, including the priest and village chief.

One must also take into account that at that time of year there were numerous [seasonal] workers inside this kaza. Since they were not registered, it is difficult to determine their precise number. God grant that the consulates and journalists exaggerated their numbers!

But if we take into account the economic importance of Adana and the fact that the massacres took place just in the working and trading season, with laborers coming from many places in Anatolia and even from distant Mosul, the number of seasonal workers should not be less than 40-50,000. Of this number, Armenians made up half, and the majority of them were murdered.

Sihni Paşa, who was appointed vali of Adana after the massacres, told me during a meeting that it was impossible that the number of Armenian victims amounted to 15,000, since according to official data the number of Armenians in the city of Adana only amounted to 13,000. But His Excellency had forgotten that 10,000 Armenians had come to his administrative district and were living in tents near the railroad station. When I spoke about this fact, he remained speechless. Let us assume that these poor people, who were here and there, outside the city and without weapons, nevertheless survived, but unquestionably the other half was lost without leaving a trace in the official statistics.

In Hadjin, where Armenians were besieged for 15 days, no massacres are said to have taken place. To this day, however, there is no news of those 3,000 Armenians from Hadjin who were in the rest of Adana province. In Hadjin, a mountain town with no economic income, the inhabitants are forced to earn their daily bread elsewhere.

Now about the non-Armenian victims. (…) Two American missionaries burned to death in the Armenian church in Osmaniye during service. In the times of Sultan Abdülhamit, women and children were spared as well as Christians of other ethnicity were spared. Even Armenian Catholics and protesters were not attacked. However, during the massacres in Adana, the perpetrators made little difference.

The Arabic-speaking Orthodox and Catholic Syriacs, who had nothing in common linguistically or otherwise with the Armenians, suffered the first 400 and the last 65 victims. The Chaldeans suffered 200 victims and the Greeks 100 victims in Adana and another 100 in the province. The Armenian Protestants counted 655 victims and the Armenian Catholics 200 victims.

It was confirmed that before the massacre, the recommendation was made to spare the Greeks. However, the Christian element was nowhere spared. A protocol confirmed that in Erzni, the most important town of the sancak Cebelbereket, there were two Greeks among the inmates when the prison there was cleared. They were also murdered, even in the presence of the local authorities.

All these facts together sufficiently testify that the Adana massacres were not merely anti-Armenian in character, but were directed against Christians as a whole and against the constitution.

Previous massacres and lootings, especially the destruction of property and houses, were not carried out with such fanaticism and without any reason as here and now.

In short, all this horror proves that a furious spectre fell upon this province. The result of the barbarism lies in the fact that the souls of the people who lived through this horror were broken and they lost their capacity for judgment.”

Excerpted from: Yesaian, Zapel: In the Ruins. Artashes Markosian (ed.), 2nd ed. Istanbul: Aras Yayincilik, 2012, pp. 319-322)

According to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, by 1918, 774,235 Ottoman Greeks were deported throughout the Ottoman Empire; of these, 3,650 were from the cities Adana and Tarsus.[14] At the same time, Adana and Tarsus served as destination for the Greek Orthodox population of Mersin:

“Tarsos and Adana (dependent on the Patriarchate of Antioch) also suffered from deportations. At the beginning of the European war the Christian population of Mersina was deported to Adana and Tarsus for military reasons, as if the military reasons did not apply equally to all the population of a town in general. At the same time the inhabitants of the neighbouring agglomerations were also deported. About seventy notables of Tarsus were exiled to the district of Aleppo in April, 1918.”[15]

Most of the Greek deportees were never seen again after the war.

“Since the April 1909 Cilician massacres, which took an especially heavy toll in Adana, tensions in this coastal region, exposed to the maneuvers of the French and British navies, had never really subsided. (…) The first harbinger of the future persecutions was the arrest, at the end of April, of 400 members of the elite in Adana, especially teachers and entrepreneurs such as Samuel Avedisian, Yesayi Bezdigian, Garabed Chalian, Mihran Boyajian, and the Bedrosian brothers. (…) Contrary to what happened

in other regions, however, these men were freed after one week in detention. The vali, Ismail Hakki Bey, an Albanian with the reputation as a moderate, probably had something to do with this.”[16]

Ismail Hakki ordered the deportation of 4,000 non-resident Armenians in Pozantı (also: Bozantı) in May 1915, but managed to get them back after a few weeks.[17] At the same time, however, the province of Adana was the one where, starting with the city of Dörtyol, the massacres began earliest in a nationwide comparison, as early as the beginning of March 1915 (February according to the Julian calendar). Indirect support for the Armenian deportees from Adana also came from Minister Ahmet Cemal, who brought about a temporary halt to the deportation from the city of Adana at the end of May 1915 and also worked to ensure that a not insignificant number of Armenians from Adana were deported to Damascus instead of the Syrian desert, where their chances for survival were far higher. [18]

Chronology of Destruction (1915)

2 March 1915: The Minister of the Interior, Mehmet Talat, ordered the arrest of the notables of Dörtyol (sancak Cebelbereket in the province of Adana), who were then hanged in public. On 12 March 1915, Dörtyol was besieged by a unit of the 4th Army Corps and 1,600 men were arrested and remanded to labor battalion (amele taburları) in Aleppo. [19]

End of April 1915: 20,000 Armenians from the kazas of Payas, Yumurtalık, and Hassa were deported to the Syrian Desert. Around 3,500 of them—essentially those individuals deported to the Damascus region—were still alive when the armistice was signed.[20]

18 May 1915: The deportation to Syria of the Armenian population of the provincial cantons of the Adana province started. Thousands of men were interned and some executed in public.[21]

20 May 1915, city of Adana: The first convoy of deportees, comprising thousands of Armenians, was sent to Syria.[22]

23 May 1915: The Minister of Post and Telegraphs decreeded that all Armenian employees of the Post and Telegraph Services in the provinces of Erzerum, Ankara, Adana, Sıvas, Diyarbekir, and Van be removed from their offices.[23]

23-27 May 1915, Hadjin (Trk.: Hacın, province of Adana): Cavalry and infantry troops invaded the city. On 27 May they proceeded with the arrest of 250 Armenian notables who were interned at the konak and at the monastery, which have been requisitioned. There, they were tortured and executed.[24]

10 June 1915, Hadjin: The deportation of 5,000 Armenians started under the supervision of Colonel Hüseyin Avni. The first convoy was made up of 150 families who were marched on foot towards Osmaniye and Aleppo via the Kiraz mountain road. The 5,000 Armenians of the neighboring kaza of Feke were deported a bit later.[25]

17 June 1915, Sis (kaza of Kozan, province of Adana): The official order to deport the Armenians, personally confirmed by the Minister of the Interior, reached the prefecture of Sis. Sixteen thousand Armenians from the town and its surrounding kazas, especially Karsbazar, were deported to Osmaniye and Aleppo under the supervision of Colonel Hüseyin Avni.[26]

7-8 July 1915, kazas of Yarpuz, Islahiye, Bahçe, and Osmaniye (sancak of Cebelbereket, province of Adana): Around 20,000 Armenians from these cantons are were deported to the Syrian Desert.[27]

Mid-August to 1 September 1915, city of Adana: 5,000 families (20,000 individuals) were deported in eight convoys to Syria under the supervision of Ali Münif, Deputy of Adana and assistant to the Minister of the Interior, Talat, and the Director of police, Adıl Bey.[28]

End of August and September 1915, Tarsus and Mersin (province of Adana): Six hundred Armenian families from these kazas were progressively deported to Syria.[29]

19 March 1916, Adana: Cevdet Bey, former Governor of Van and commander of the notorious ‘butcher battalions’ (kasab taburları), is appointed head of the province of Adana.[30]

At the end of 1919 150,000 Armenian escapees are found in the province of Adana, which remains under French administration until November 1921.[31]

Raymond Kévorkian concluded that “it seems more than probable that the fact that part of the Armenian population of Cilicia was allowed to stay home, and that another part of it was deported to the least deadly zones, resulted from buying off local government officials on a broad scale.”[32]

Adana as Destination for Christian Deportees

The Ecumenical Patriarchate mentioned that Greek Orthodox residents of Mersin were deported to Adana in 1914.[33]

Cilicia under the French Mandate (1919-1921) and its Reconquest by the Kemalists

The Sykes-Picot Agreement 1916

“During the (…) period of French mandate rule over Cilicia, the mandate area included, in addition to the province of Adana, the sancak of Maraş, the sancak of Urfa, and parts of the sancak of Aleppo [see the relevant sections on these three sancaks].

As early as May 1916, Great Britain and France had divided their spheres of interest in the Middle East in the agreement negotiated between Sir Mark Sykes and Francois Georges-Picot. According to this agreement, the Christian-populated coastal region of Syria was to be placed under direct French mandate, France was to be allowed to exert influence over the four cities of Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo in the interior of Syria, and was to receive a mandate over Lebanon, the province of Adana, and a piece of the non-Russian part of Kurdistan. Britain, on the other hand, received Transjordan and a part of Mesopotamia. Russia was granted the European part of Turkey with the capital Constantinople as well as the Straits. The Asian part of Turkey was also divided between Russia, Britain and France into a Turkish-Greek region on the coast of the Archipelago, a Turkish one in the interior and a Kurdish-Armenian one in the east. Two-thirds of the Kurdish Armenian territories-namely the provinces of Van, Bitlis, Erzurum, and Trebizond, which had already been conquered by Russia in 1916-were to fall to tsarist Russia, but these provisions lapsed after the October Revolution of 1917. France, on the other hand, claimed the provinces of Sivas, Diyarbekir, Kharput and Mosul in addition to Cilicia. It demanded the evacuation of Cilicia from British troops in 1919 as it sought to assume its mandate according to the Sykes-Picot agreement. The change in the military occupation of Cilicia took place on 1 November 1919.

The Repatriation of Armenian Refugees to Cilicia

While the Entente opposed the return of Armenian refugees to Western Armenia even after it first became apparent that the majority of refugees in Transcaucasian Armenia were doomed to certain starvation, the repatriation of Armenian refugees or their resettlement in the French Mandate territory was desired.

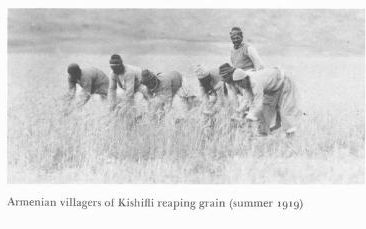

At the time of the Mudros Armistice (1918), the Allies counted 200,000 Armenian refugees in Syria, most of whom were languishing on the brink of starvation. It was decided to resettle them in Cilicia under the protection of the Allies. Thus, in 1919, 120,000 Armenians arrived in Cilicia, and 50,000 more were repatriated to the western part of Asia Minor[34]; according to Paul du Véou, 60,000 deported Armenians went to Adana, where before the war ca. 50,000 Armenians had resided out of a total population of 80,000, 24,000 to Maraş, where the pre-war Armenian population in the entire sancak Maraş had been 86,000, 8, 000 to Hadjin with a pre-war Armenian population of 30,000, 1,000 to Hasanbeyli, 12,000 to Dörtyol, 1,000 to Osmaniye, 1,500 to Misis, 1,200 to Incirlik, 4,000 to Tarsus, 2,000-3,000 to Mersin, and 1,000 to Zeytun.[35]

Among the 120,000 repatriates, there were 50,000 Armenians from Constantinople and various cities in Asian Turkey.[36]At the same time, 8,000 Muslims from Erzurum, Van and Kharberd [Elazığ], who had been settled on Armenian lands by the Young Turks in 1915, were sent back to Western Armenia from Cilicia.[37] Thus, in 1920, the ethnic picture in Cilicia was as follows: the Armenians constituted the largest population group in the French mandate territory with 120,000, followed by 100,000 Arabs, 30,000 Kurds and Kizilbash, 28,000 Greeks (mostly of Ottoman nationality), less than 20,000 Turks, 15,000 Circassians, and 5,000 Chaldeans and Syriacs. [38]

The repatriates, or new Armenian settlers, found a country plundered and devastated by the Turks, where churches, schools and the fields had been largely destroyed and Armenian property looted or distributed to the Muslim population. Repatriates and members of the Armenian Legion searched in vain for surviving relatives and friends who had perished between 1915 and 1918. The number of Armenian victims in Adana was 40,000, in Dörtyol 24,000 and in Hadjin 20,000 (…).

The French had left the administration to the local Ottoman authorities, although they reserved the right to appoint officials.

The Reconquest of Cilicia by the Kemalists

(…) France’s true motives for occupying Cilicia and returning Armenian refugees there, however, were less humanitarian than economic. France hoped, as General Édouard Brémond wrote in a preface in 1937, for the rich cotton yields of the Cilician plain. Armenians, known for their industriousness and loyalty to France, were to play an important role in the colonization of this land. However, out of the same economic-political speculations, Cilicia was dropped by the French as early as 1921, when its possession threatened to strain Franco-Turkish trade relations. At that time, France owned 61 percent of the Ottoman tobacco monopoly (Régie des tabacs), as well as significant concessions for Turkish railroad construction, mining, ports, and so on.[39] (…) In the interest of preserving these economic advantages, France was also the first European power to enter into negotiations with the Kemalist rebels in Ankara, who had been boycotted internationally until then, and thus to pursue a de facto recognition of the Turkish nationalist regime. (…)

The Kemalist nationalist resistance movement in Cilicia had been forming since June 1919. In the second half of that year, Mustafa Kemal rose to become the recognized nationalist leader, and in November 1919 he succeeded in dissolving the cabinet of the government in Constantinople and holding new elections. Shortly after the military occupation of Cilicia by the French, High Commissioner Georges-Picot visited Mustafa Kemal in Ankara in December 1919.

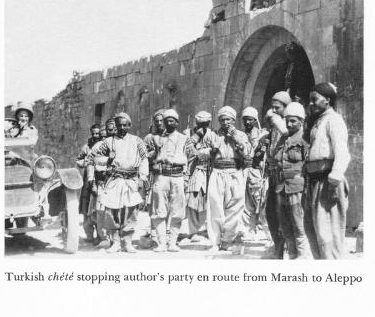

Mustafa Kemal, who had taken over command of the Second and Seventh Ottoman Armies from the German General Otto Liman von Sanders, had already laid the groundwork for active resistance by Turkish and Kurdish nationalists against the Mandate forces before the Ottoman military was evacuated from Cilicia.[40]He had the çeteler, the notorious Turkish irregulars or guerrillas, supplied with weapons and ammunition in various Cilician towns such as Ayntap and Maraş, while the local sections of the Young Turk ‘Unity and Progress’ Committee organized the armed resistance. At the end of 1919, the Kemalist resisters in Maraş began to test the determination of the French to defend Cilicia militarily. (…)

During the nationalist struggles in the French mandate territory of Cilicia, the rest of the Armenian urban population that had defied the Ottomans for centuries was also wiped out. These were the towns of Hadjin (Trk.: Saimbeyli) and Zejtun (Trk.: Süleymaniye), both fortress-like situated in the Taurus and known for their freedom-loving and battle-hardened population. [For details, see kaza Hadjin.] (…)

Despite the acute danger that threatened the Armenians as a population group that was particularly hated by the Turks and, moreover, had been allied with the Turkish war enemy France, the commander of the French troops in the Middle East, General Henri Gouraud, did not order the evacuation of the Armenians, but on the contrary ordered on 12 November 1921 that the Christians should remain in their places of residence. At the same time, Britain, angered by the Kemalist-French separatist negotiations, refused to accept refugees in Palestine and Egypt and issued visas for Cyprus only to those who were able to pay for passage in first or second class. Only French-influenced Lebanon and Syria guaranteed asylum to the refugees. An Italian ship took on board 3,000 orphans in Mersin, and Greek ships carried thousands of refugees. [41]

The Kemalist rulers also denied the Armenians departure from Cilicia at first and enriched themselves with their labor and their last belongings. (…) Four months after the withdrawal of the French from Cilicia, on 20 April 1922, the confiscation of “abandoned property” in all areas “liberated from the enemy” was decreed by law. This meant, in effect, not only the expropriation of Armenians who had perished during the genocide or were refugees outside Turkey, but also affected those Armenians who had left Cilicia after the French withdrew. The law clearly violated the Franco-Turkish Ankara Agreement ( 20 October 1921), which was supposed to ensure the protection of Armenian property in Cilicia a few months earlier. [42]

The final evacuation of Cilicia took place between 1 December 1921 and 4 January 1922. In this short period of time, the French evacuated by train and ship 54,451 Christians, including more than 40,000 Armenians. About 60,000 other Christians left Cilicia by land without official permission to leave.[43] Of the total of about 100,000 to 105,000 Armenian refugees, 30,000 made their way to Cyprus and Egypt and 75,000 to Syria.[44] According to official French figures, 8,760 Christians remained in Cilicia after 4 January 1922, 5,000 of whom lived in the Killis-Ayntap region alone, including only 637 Armenians. [45] (…)

France’s colonial adventure in Cilicia thus cost the lives of 20,000-30,000 Armenians and turned about 100,000 more into refugees again after barely two years.”

Excerpted and translated into English from: Koutcharian, Gerayer: Der Siedlungsraum der Armenier unter dem Einfluss der historisch-politischen Ereignisse seit dem Berliner Kongress 1878: eine politisch-geographische Analyse und Dokumentation [The Armenian settlement area under the influence of the historical-political events since the Congress of Berlin in 1878: a political-geographical analysis and documentation]. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1989, pp. 157-164