Toponym

The Turkish form of the name is derived from the original ancient Greek name Irakleia (Ηράκλεια; Latin: Heracleia Kybistra).

History

Possibly Ereğli is identical with the Hittite Ḫupišna, which was a local cult center of the goddess Ḫuwaššanna. In the early Iron Age, Ḫupišna was a neo-Hittite small state in the land of Tabal.

In Hellenistic and especially in Roman times, the city was an important place under the name of Herakleia Kybistra, at the point from where the road to the Gülek Pass (Cilician Gates; Armenian: Kuklak) leads into the mountains. It was located on common military routes and was therefore plundered more than once (among others in 806 and 832) by the Arab invaders of Asia Minor. In 806, the Abbasid caliph Hārūn al-Rashīd occupied the city for a short time.

In Byzantine times, the city belonged to Cappadocia. For a short time, it belonged to the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia as Kybistra. In August 1097, the crusader army of the First Crusade, on its way to Antioch, defeated at Heraclea the combined forces of the Danishmendids and the Emir of Cappadocia. During the Crusade of 1101 it was the scene of a failed battle of 15,000 men led by William II, Count of Nevers, which left the Crusaders weak en route to Antioch.

It became Turkish (Seljuk) in the 11th century. Ereğli is also known for being the first capital of the Karaman Beylik founded by Nure Sufi Bey. The Karaman state was renowned for being a consistent nuisance to Ottoman dominance in Anatolia, being one of the few Anatolian beyliks to retain sovereignty well past Fatih Sultan Mehmet‘s conquest of Istanbul. Since 1466 it belonged to the Ottoman Empire. It was also the first political entity in Anatolia to proclaim Turkish as an official language.

Kybistra is a titular bishopric of the Catholic Church.

Destruction

The German missionary and reverend Hans Bauernfeind, who had left the Bethesda Mission Station for the Blind in Malatya and was on his way to Constantinople with his relatives, noted about the Ereğli train station crowded with Armenian deportees:

„Eregli train station, August 23, noon, 4 o’clock – So now we have really come so far; only we can hardly believe it because of tiredness. We left Bor yesterday (August 22, 1915, ed.) evening at 10 o’clock (…) But what a great moment it was when we reached the railroad line! We arrived here at 10:00, had a lot of work in the Han [caravanseray], food in the hotel, everything downright awful. Everything is teeming with Armenians, thousands of whom are camped outside, or, the rich, living in the city. There is little sense of misery here; (…). They have no idea of the impending dangers [they are in]. (…)”[1]

“The 1,000 Armenians of the Ereğli community had been dispatched toward Syria a few days earlier by the kaymakam Faik Bey, the police chief Izzet Effendi, Yusufzade Nadim, the head of the Office of Deportations, and Major Hasan Bey, the military commander of Ulukışla.”[2]

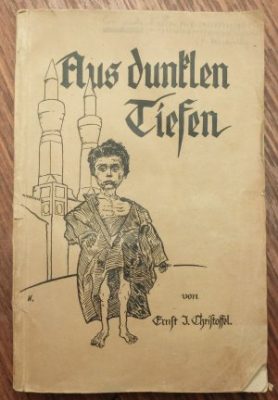

When Bauernfeind’s brother-in-law, the mission founder and leader Ernst Christoffel, returned to Malatya from Constantinople in early March 1916, he noted about Ereğli:

“In Ereğli I left the train, because from here I wanted to reach Malatia [Malatya] via Caesarea and Sivas. Hiring a travel carriage caused great difficulties. (…) The majority of the Arabajis (coachmen) were Armenians. Since they were the most reliable, one usually hired one. Naturally, the same were now completely absent. Furthermore, the military administration had confiscated the majority of both passenger cars and trucks (…) The governor, to whom I turned, promised help, but

Erlebnisse eines deutschen Missionars in türkisch Kurdistan während der Kriegsjahre 1916-1918. (From Dark Depths: Experiences of a German missionary in Turkish Kurdistan during the War Years 1916-1918). Berlin 1921 (Cover page)

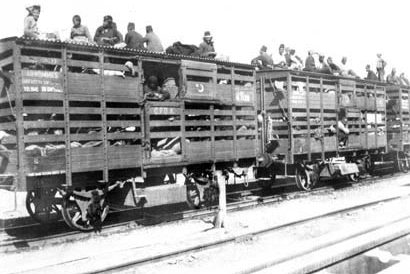

did nothing for several days. In those days I got to know some Armenian families who, because they were craftsmen, had been spared from deportation until that time. Frightened and intimidated, they hardly dared to go out on the streets, and even I visited them only in the evenings so as not to cause them any inconvenience. With great love they fed a number of infants whom they had picked up on the road behind the hedges and fences after the passage of the Christians going into exile. (…) They told horrible stories about the way the exiles were sent, how they were crammed into cattle cars. On the Baghdad railroad there are cattle cars for the transport of goats and sheep, which are divided in the middle in such a way that there is an upper and a lower space, so that animals can be loaded above and below. The exiles were loaded into these wagons like animals. Standing was not possible, at most squatting, and even that was hardly possible because the wagons were overcrowded. Men, women and children, the healthy and the sick, all mixed up, were transported in this way for days. Sick people died in the process, pregnant women gave birth. What I was told here in detail, I had heard before in Eski Shehir [Eskişehir] and Konia [Konya]. But however deep an impression what I heard made on me, it was blurred by the terrible things I heard and saw later.”[3]