Situated on the southern slopes of the Armenian Taurus and in the basin of the Koghbadzor (now Khulp or Pasursu) river, the mountainous region of Khulp formed a district in Western Armenia, with the village Khulp as administrative center. Khulp stretches from the Andok and Kerpin mountains, extending along the left bank of the Aradzan (Trk.: Murat) river to the Genç mountains. At its eastern border is Andok (2830 m), on the west is Kasan (2080 m), on the north are the Koghba (now Mir-Ismail) mountains.

The kaza Khulp had a warm climate, fertile soil and rich vegetation. Selected varieties of grapes and fruits were growing.

Toponym

According to the Armenian historian Nikolai Adonts (Նիկողայոս Ադոնց – Nikoghayos Adonts, 1871-1942), Khulp corresponds to the Urartian Ulluba or Khabkh country.

Variants of the Armenian placename Khulp were Կալաբ (Kalab), Կողպ (Koghp), Կուլաբ (Kulab), Կուլբ (Kulb), Կուլպ (Kulp), Կուլփ (Kulp’), Ղուլփ (Ghulp’), Քուլփ (K’ulp’).

History

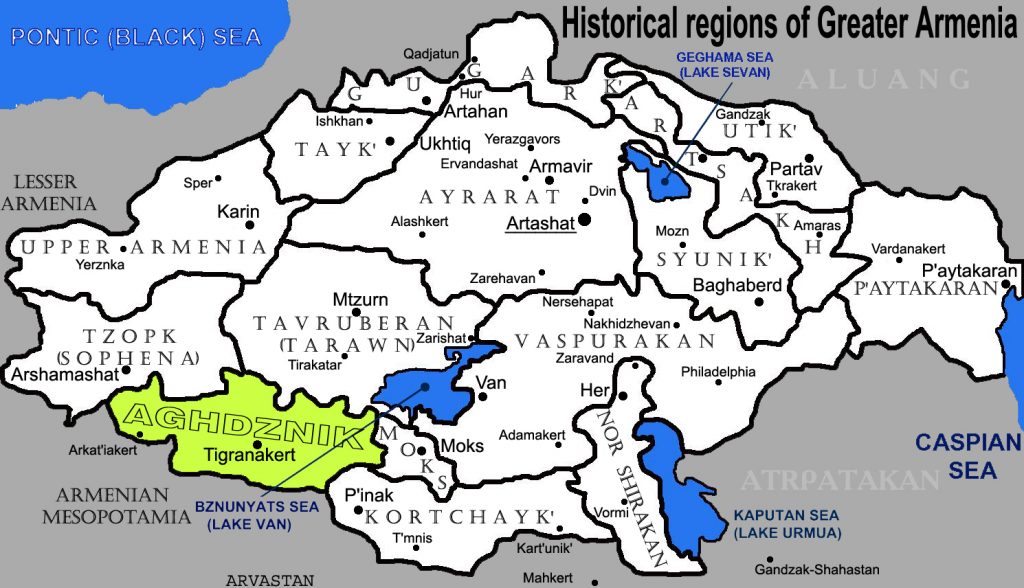

The territory of Khulp was part of the Sanasunk (Sasun) district of Aghdznik province of Greater Armenia, which formed one of its eight provinces. The Tigranakert-Artashat trade road passed through there. After falling under Ottoman rule in the 14th century, Khulp was incorporated into the province of Diyarbekir until 1864. It had a semi-independent government. In the 1880s it became part of the Bitlis vilayet. Until the 15th century Khulp was inhabited by Armenians only. Then nomadic Kurdish tribes started to immigrate to the territory of Khulp, later settling in the abandoned settlements of Armenians.

Population

In 1909, the kaza Khulp had 113 settlements.

At the beginning of the 20th century, more than 5,000 Armenians of the kaza lived mainly in the coastal villages of Koghbadzor. Large Armenian-populated villages were Endzakar (about 140 inhabitants, with Surb Gevorg monastery as a place of pilgrimage), Gazken (a medieval village of 2,000 houses, and in the early twentieth century 100 Armenians), Aharonk (the administrative center of the 1870s), Ehub (Eyub), Geghervank (Geghervan), Shughek, and Pasur, a rural town 23-24 km south-west of the village of Khulp, on the right bank of the Pasur River. It was the center of Khiank nahiye, or village group. At the end of the 19th century Pasur had 40 Armenian houses and 40 Kurdish houses (in 1909: 36 houses with 296 Armenian inhabitants).

The inhabitants of the kaza Khulp were engaged in gardening, silviculture, weaving, etc.

During the 1915 genocide and even before that, among the forcibly Islamized Armenians of Khulp there were those who preserved their Armenian identity through inter-community marriages or became linguistically completely Kurdified. Many of them later became active members of the Kurdish movement. The Armenians of Khulp were completely Islamized during the Genocide and in the following years, but preserved some cultural features of their original identity, such as some Armenian national dances and Armenian cuisine. “There are close to 6000-7000 Islamized Armenians in the western region of historic Sassoun, Khulp, which now comprises the modern province of Diyarbekir.”[1]

Destruction

Armenian-populated villages of Khulp were looted and destroyed in 1895 and 1896. Survivors of the 1915 genocide took refuge in Eastern (Russian, since 1920 Soviet) Armenia or were assimilated to the Kurdish majority population and Islamized. The Kurdish tribes that had most actively participated in the genocide were established in the region. The remaining Armenians of the previous Khulp kaza belong to these tribes as slaves and in feudal dependency.[2]

Sophia Hakobian: A hundred years after the genocide: The Islamized and Crypto-Armenians of Khulp (2015)

“(…) The Armenian villages of Khulp are: Aharonk, Pasur, Khuruj, Parka, Shirnas, Artunk, Garik, Tiaha, Jikse.

The Armenian villages of Khiank are: Arkhount (also Արխոնք – Arkhonk’, Արքոտ – Arkot’), Berm, and Bade.

The Armenians of Khulp and Khiank suffered a gloomy fate after some of the most deadly Kurdish tribes who participated in the genocide of Armenians settled in these regions. The surviving Armenians, besides being looted, were then forced to serve these tribes as slaves.

There were some among those who were Islamized before and during the genocide who managed to preserve their identity thanks to repeated inter-communal marriages, though they gradually began speaking only in Kurdish. Later on, many of them would even go on to play important roles in the Kurdish movement.

During the genocide and in the years that followed, the entirety of the Armenian population of Khulp converted to Islam.

They’ve retained some Armenian national dances as well as certain Armenian cuisine specialties. The Armenian families of the Khuruj, Pasur, and Parka villages are very large and active. These days, a national awakening of sorts seems to be brewing among them, reflected especially in the willingness to assign Armenian names to the children, in the increasing interest in the Armenian language and Armenian culture, in the gradually flourishing links with relatives in Armenia and in the Diaspora, and so on. While there are some exceptions, most of them only marry other converted Armenians.

The Kurdified Armenians of the Bade village now live in Silvan, are active participants in the Kurdish national movement and had already broken their links with other Armenians long ago. The same can be said of some descendants of the sole surviving family of the Berm village, who now live in the center of Batman; they’ve similarly forgotten about their Armenian roots a long time ago. Nevertheless, some of their relatives have gone the opposite direction, preserving their national and religious identity and, later, settling in Istanbul. The inhabitants of the rest of the villages in Khulp, however, have all abandoned their Armenian identity.

The Armenians in the Arkhount village also merit particular attention, as some of them have remained Christians to this day. Within the Khiank region, they’re the ones who have been most successful in preserving their national identity and religion.

The number of this village’s population has periodically fluctuated; at one point, there were 42 homes. Some of those Armenians who had been forcefully converted to Islam had covertly managed to preserve certain national and religious traditions, habits, and rituals for quite a long time, and in some cases, if conditions were to allow, they would be open about their Christian lifestyle. And even though there were no fluent Armenian speakers left among them, anyhow, many of the parents would later settle in Istanbul where they would convert their children and send them to Armenian schools.

Some of the Armenians of the Arkhount village abandoned their homes as the Kurdish PKK began directing military campaigns against the government; this was when villagers would be required to cover for the pro-government village troops and fight against the Kurdish rebels. A significant portion of the Kurdified Armenians of Arkhount refused to fight against the PKK and moved to Western Turkey, primarily Istanbul. Today, the Armenians of Arkhount have their own Union of Expatriates in Istanbul, the Herendi (Kurdish for Arkhount) Armenian Union.

Another reason for the exodus of the Arkhount Armenians was the periodic repression carried out by their Muslim neighbors, which prompted some of the Armenians to convert to Islam while others preserved their faith and left the village. Many of those who converted did so purely on a formal basis so as to avoid persecution. After accepting Islam, they maintained the tradition of inter-communal marriages, separating themselves from the Kurds.(…)”

Excerpted from: Hakobian, Sophia: Sassoun and the Armenians of Sassoun after the Genocide and up to this day – part II. “Horizon”, 27 July 2016, https://horizonweekly.ca/en/sassoun-and-the-armenians-of-sassoun-after-the-genocide-and-up-to-this-day-part-ii/