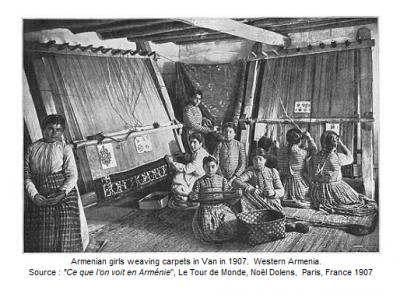

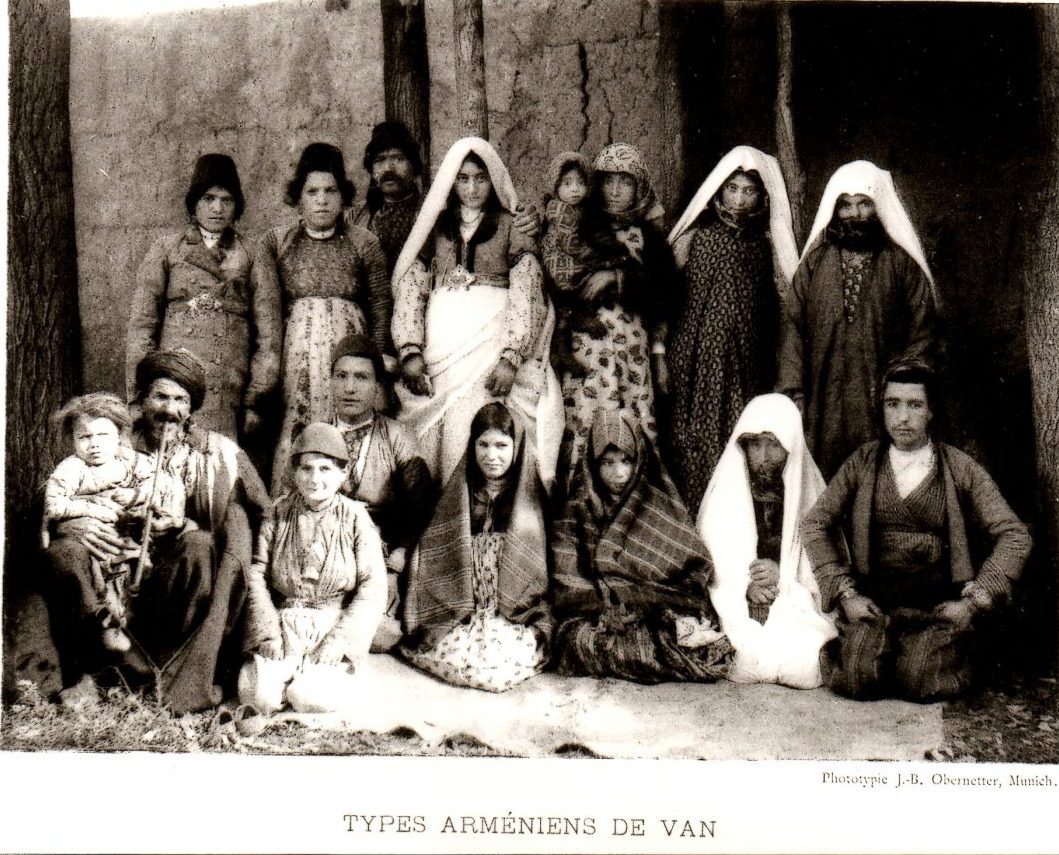

Population

“If we include the population of the caza or neighborhood of Van, we shall probably not err much in arriving at a total of at least 64,000, made up by 47,000 Armenians and 17,000 Mussulmans. Consul Taylor in 1868 reckoned the inhabitants of ‘Van and the neighborhood,’ by which he would appear to mean of the town and caza, at 17,000 Mussulmans and 42,000 Christians. For Christians one might almost write Armenians.”

Source: Lynch, H.F.B.: Armenia: Travels and Studies. Vol. II (The Turkish Provinces). London: Longmans, Green, and Co. (Reprint Beirut: Khayat, 1965; 1967; 1990, p. 79)

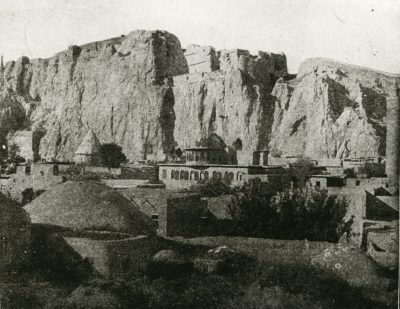

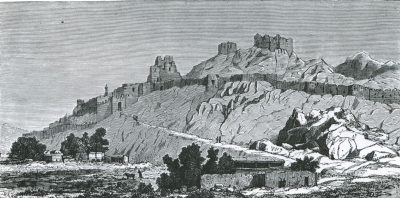

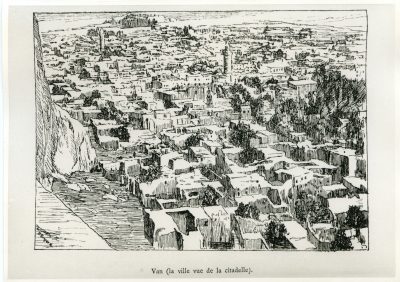

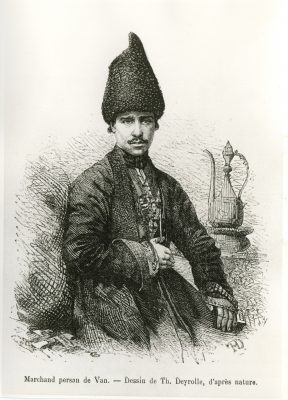

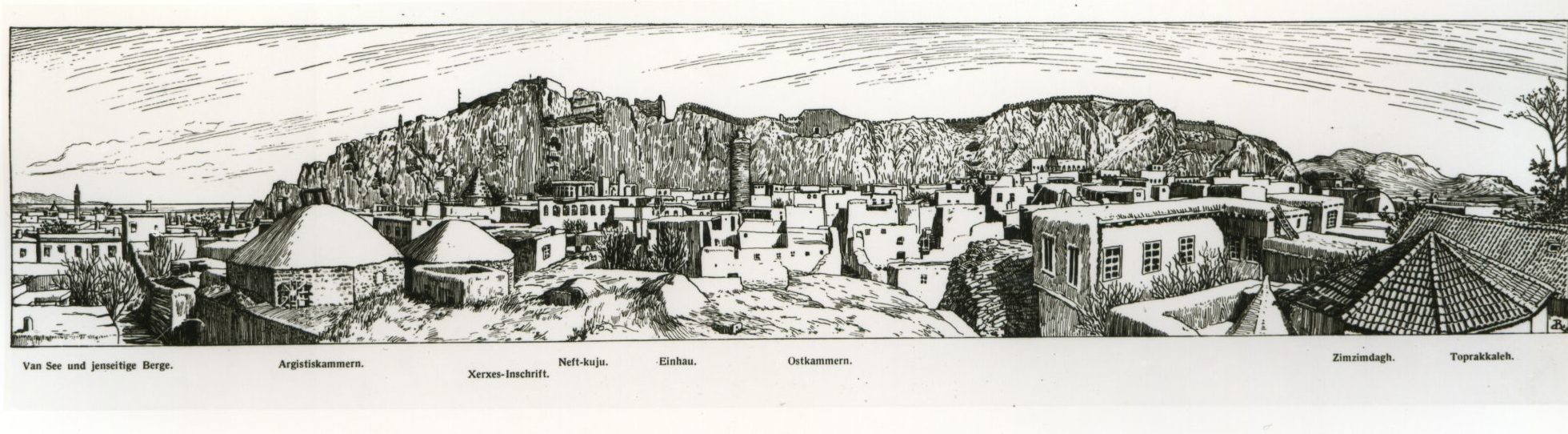

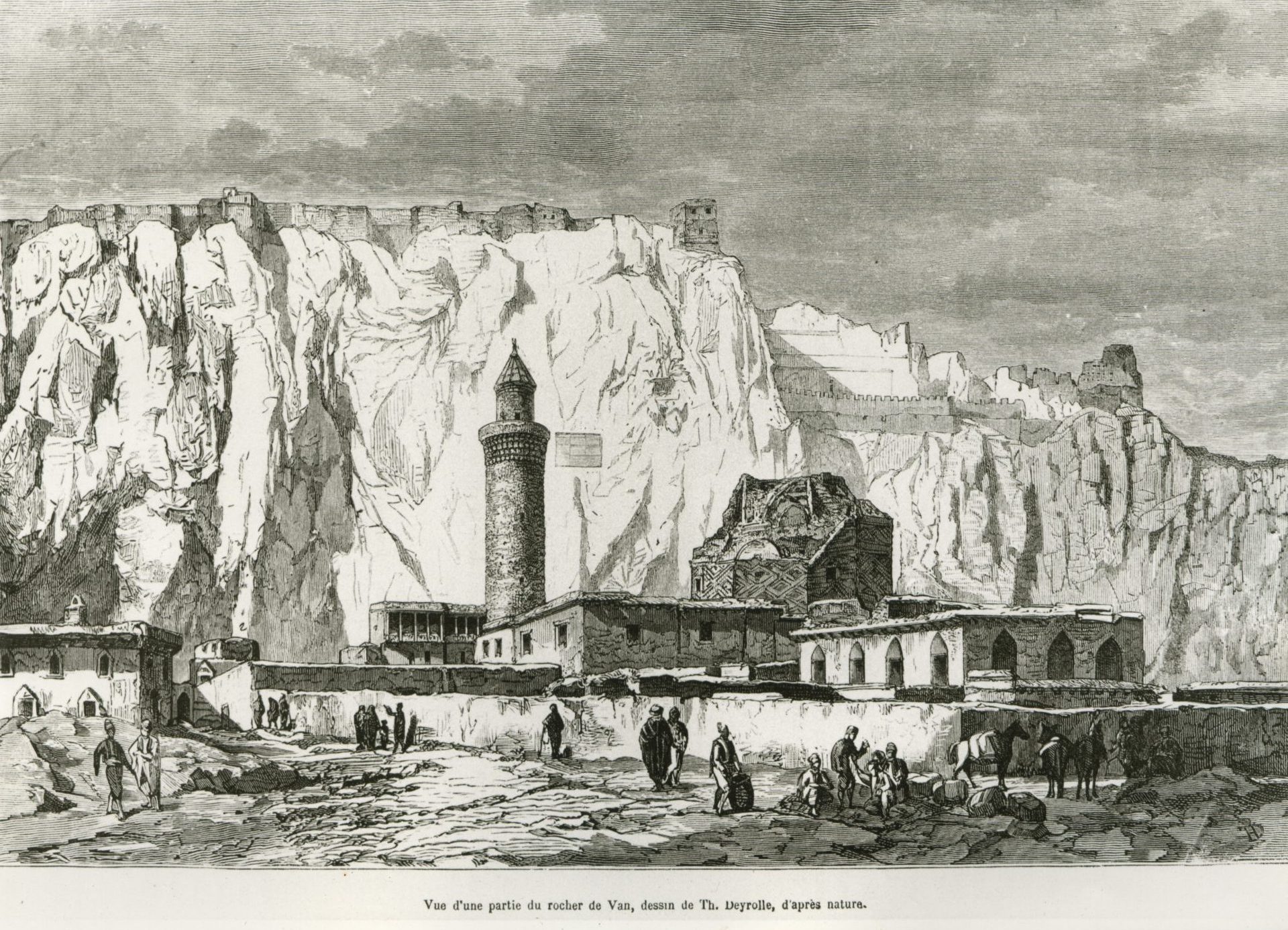

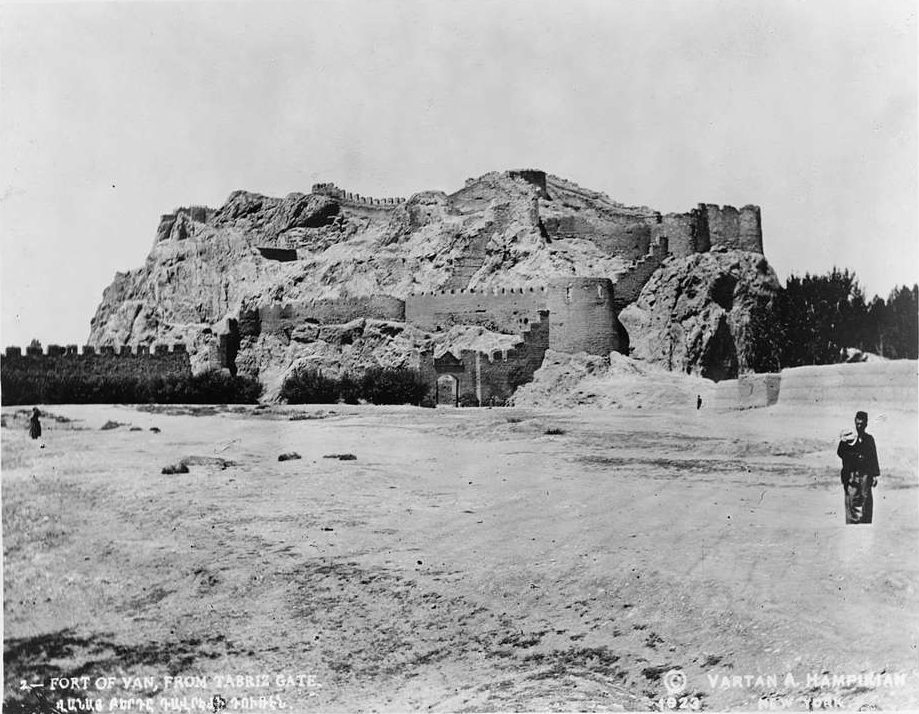

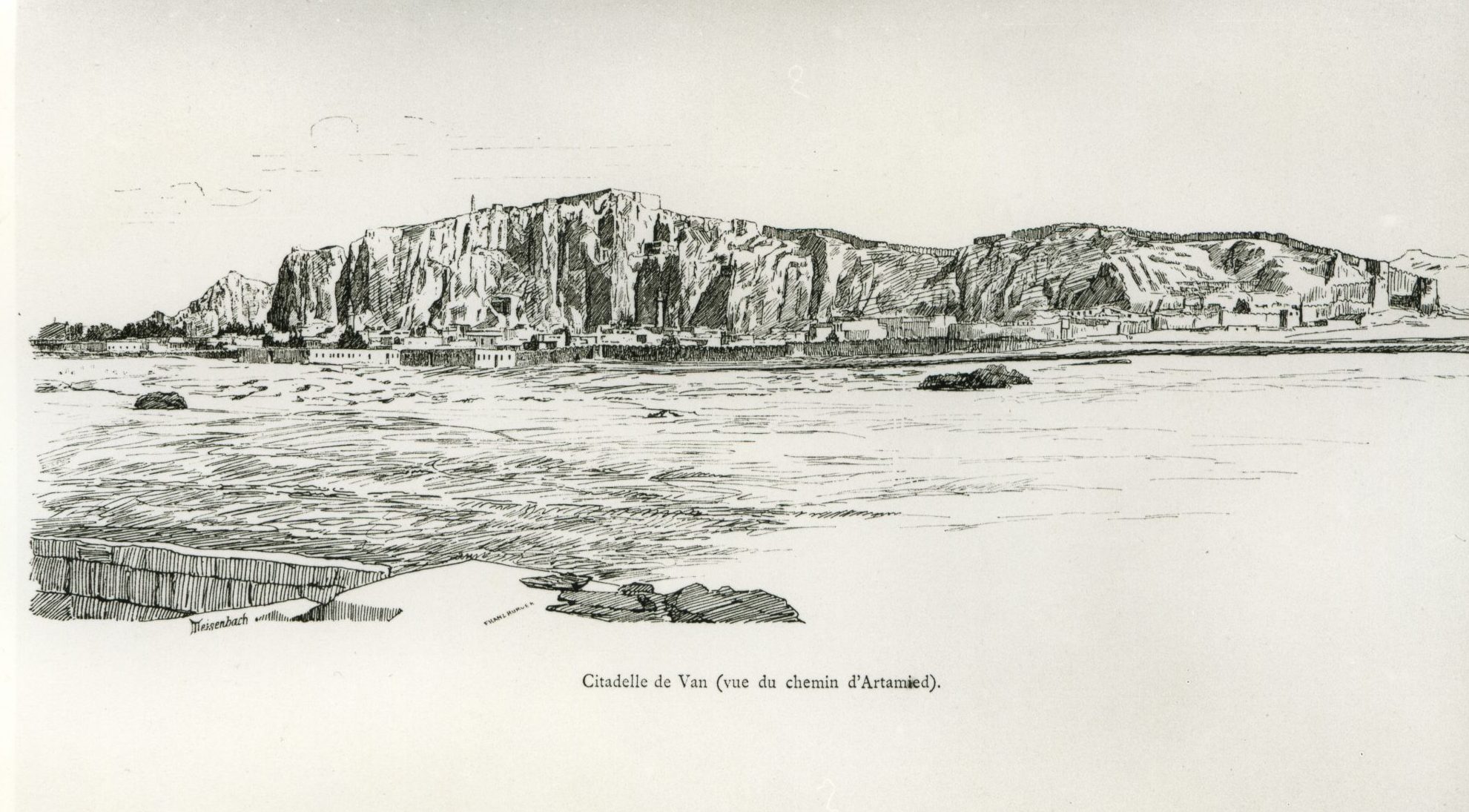

Van City

“Van was one of the most beautiful cities of Asiatic Turkey – a city of gardens and vineyards, situated on Lake Van in the centre of a plateau bordered by magnificent mountains. The walled city, containing the shops and most of the public buildings, was dominated by Castle Rock, a huge rock rising from the plain, crowned with ancient battlements and fortifications, and bearing on its lakeward face famous cuneiform inscriptions. The Gardens, so-called, because nearly every house had its garden or vineyard, extended over four miles eastward from the walled city and were about two miles in width.

The inhabitants numbered fifty thousand, three-fifths of whom were Armenians, two-fifths Turks. The Armenians were progressive and ambitious, and because of their numerical strength and the proximity to Russia the revolutionary party grew to be a force to be reckoned with.”

Source: Grace Higley Knapp from Van, in a letter of May 24, 1915, to Dr. Barton; reprinted in: The Treatment of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire 1915-16; Documents presented to Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, by Viscount Bryce. London: Sir Joseph Causton and Sons, Ltd., 1916; Reprint Beirut 1979, p. 32

Van City towards the close of the 19th century

“At the time of my visit they [the Armenian inhabitants of Van] numbered two-thirds of the population of the town and gardens of Van. This proportion has no doubt been reduced by recent events; but it is almost equally certain to be redressed. The fecundity of this people is not less remarkable than their persistency; and their presence is needed by the officials who exploit the land. It would seem that the Armenian inhabitants of Van have been increasing during the present century. There can be little doubt that the proportion which their numbers bear to those of the Mussulmans has been tending to become greater. Consul Brant records that in the year 1838 Van contained not less than 7000 families, of which only 2000 ascribed by him to the Armenians. This estimate presents a population of 35,000 souls, of whom 25,000 would be Mussulmans and 10,000 Armenians. The total agrees approximately with the most reliable statistics which I was able to obtain. At the time of my visit the town, including the gardens, was believed to be inhabited by 30,000 people; but the Mussulmans numbered only 10,000 to the 20,000 Armenians. (…)

Some quarters in the gardens are peopled exclusively by Armenians, some by Mussulmans, and some by both alike. (…)

The tall poplars and luxuriant undergrowth hide the houses of the suburbs as you approach Van from the plain in the south. (…) Extremely picturesque are some of these lofty houses, with verandahs disposed in various and fanciful manners (…). Here in the gardens are the private residence of the Vali or Governor of Van and of the principal officials. Most of the rich Armenian merchants have their dwellings among these quarters, where are also situated the various European Consulates. It is here that are housed the principal schools, and are located the most considerable of the churches. It is therefore scarcely correct to speak of the garden town as a suburb. (…)

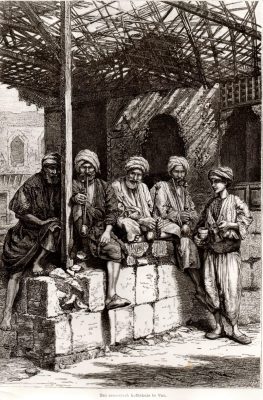

The Armenian subject majority spend lives which are certainly laborious and create whatever wealth the city possesses. The Mussulman dominant majority grow Chafunds. Over all resides an important official of little ability and no education; and a few troops, under the orders of an independent commander, who is a center for intrigue, redress the balance in favor of the least enlightened and most corrupt.

(…) Commerce and industry find in the Armenian population of Van a soil in which they would flourish to imposing proportions under better circumstances.

(…) There must exist a trace of light in every gloomy picture; and in Van the ray falls upon a little band of artisans and craftsmen as well as upon a few of tradesmen and merchants. These elect are without exception Armenians. Our money matters were adjusted with a promptitude and a spirit of honesty which revealed capacities that came as a surprise after my experience in Russian territory. Yet there is here no bank in the proper sense of the term. (…)

Some acquaintance with the outside world is derived by the citizens as a result of the immemorial custom among the male Armenian inhabitants of migrating for a number of years to Constantinople and returning home when they have amassed a certain competence.”

Source: Lynch, H.F.B.: Armenia: Travels and Studies. Vol. II (The Turkish Provinces). London: Longmans, Green, and Co. (Reprint Beirut: Khayat, 1965; 1967; 1990, p. 79ff; 83, 89ff.

Artamat – Արտամատ / Ardamad / Artemit(a) – Edremit / Sarmansuyu

Located just 18 kilometers from the provincial capital of Van, Artamat was once the summer resort for wealthy Van residents. The historian Tovma Artsruni (9th/10th century) traced local history back to a castle built by King Artashes (ruled 189-160 B.C.). Known in Greek and Latin as Artemita, or Adramyttion (Άδραμύττιον), the place name was attributed to the Greek goddess Artemis. From 1660 to 1928 it was officially called Edremid, since 1990, after various name changes, again Edremit.

In the 10th century Artamat was known as a feudal city with a population of 12,000. It was renowned for the best apples in all Armenia.

At the beginning of the 19th century Artamat had approximately 500 houses, 435 of which were Armenian, and 65 Turkish. After the massacres of 1894-1896 the number of Turkish houses increased to 400 Turkish families (against 200 Armenian families). In 1914, the number of Armenian households has further decreased to 130 (720 persons). At that time there lived also 2,500 Kurds in Artamat, a Greek and an Assyrian (Syriac) community. At that time, Artamat had 10 Armenian churches and one Greek-Orthodox church. After the legal owners were massacred, thousands of their historical monuments were annihilated as well.

While Armenians lived mainly in the central part of Artamat, Turks settled near peripheral gardens and fields.

Further Reading: The situation of Armenian sacral architectural heritage in Artamat / Sarmansuyu

http://www.virtualani.org/edremit/index.htm

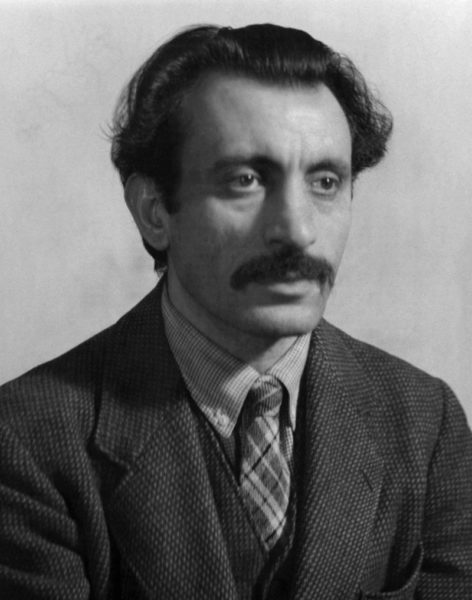

Fountain Memorial to Armenian Painter Gorky Damaged in Turkey

The prominent Armenian-American painter Arshile Gorky was born in Edremid. In 2015, Edremid district municipality built a fountain in commemoration of him, continuing a tradition of commemorating the departed by providing water for residents and passers-by.

Four sides of the fountain were embellished with details about Gorky’s life in Turkish, Armenian, Kurdish and English, with water pouring from each of them. The fountain’s architects used special stones from the region, and it was built close to Gorky’s former family home.

The monument had suffered several attacks in the past, especially after a government-appointed mayor let the fountain fall into ruin again.

Over time, spouts on all four sides were damaged and blocked, while Gorky’s name was scratched out. In the most recent incident, the signs depicting Gorky’s life story were scratched out.

When asked why the water had been shut off, the municipality under the appointed mayor told reporters it had been a measure due to insufficient water levels. Municipal officials denied any knowledge of damages.

Gorky, born Vostanik Manoug (Manuk) Adoian (Atoian) in 1904, fled to Russian-controlled territories to the east during the 1915 Genocide with his mother and three sisters. He lost his mother to starvation in Yerevan in 1919, and emigrated to the United States in 1920, where he died in 1948. He is considered one of the foremost modern American painters.

Excerpted from: “The Armenian Mirror-Spectator”, 3 February 2022, https://mirrorspectator.com/2022/02/03/fountain-memorial-to-armenian-painter-gorky-damaged-in-turkey/

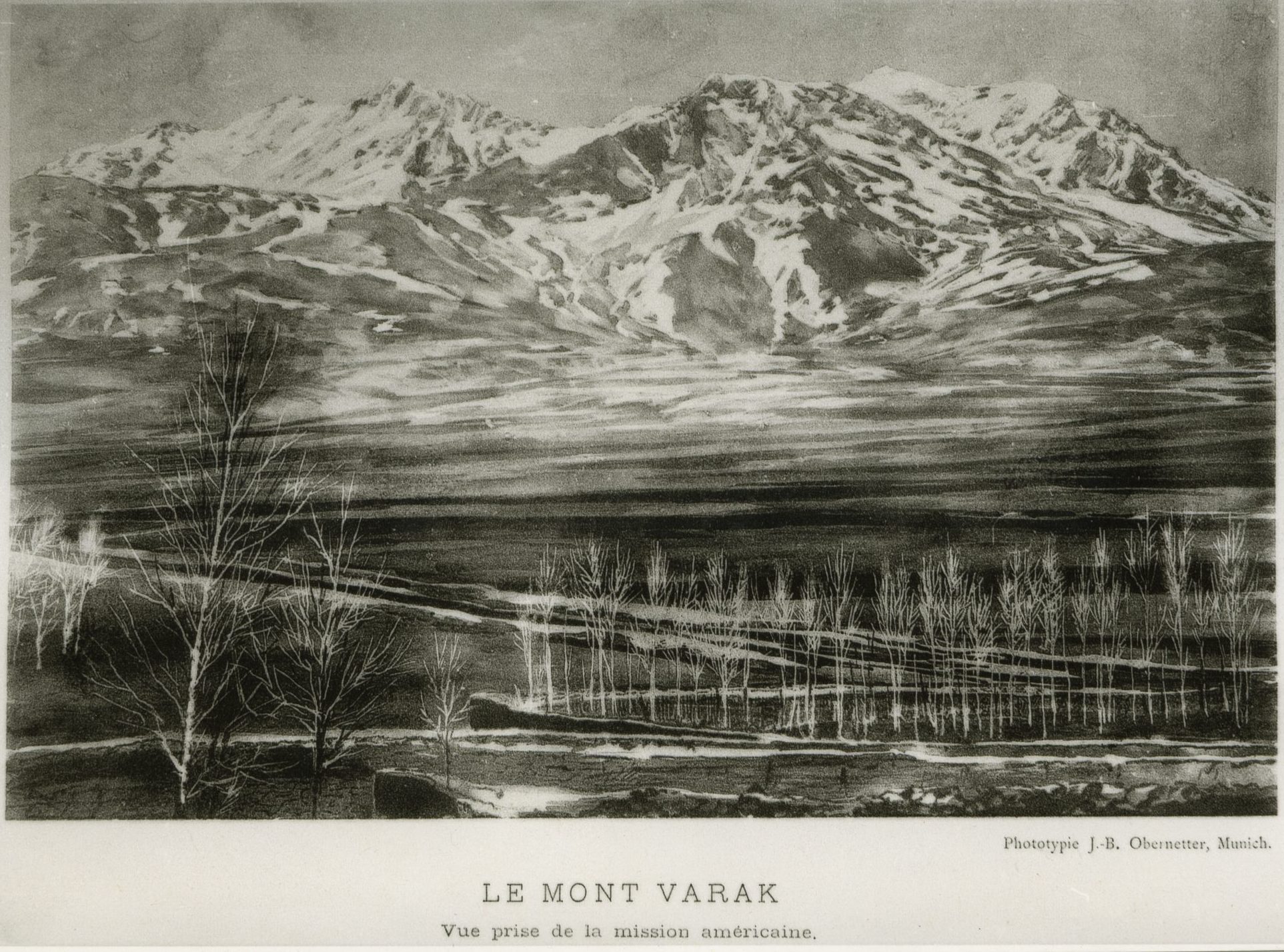

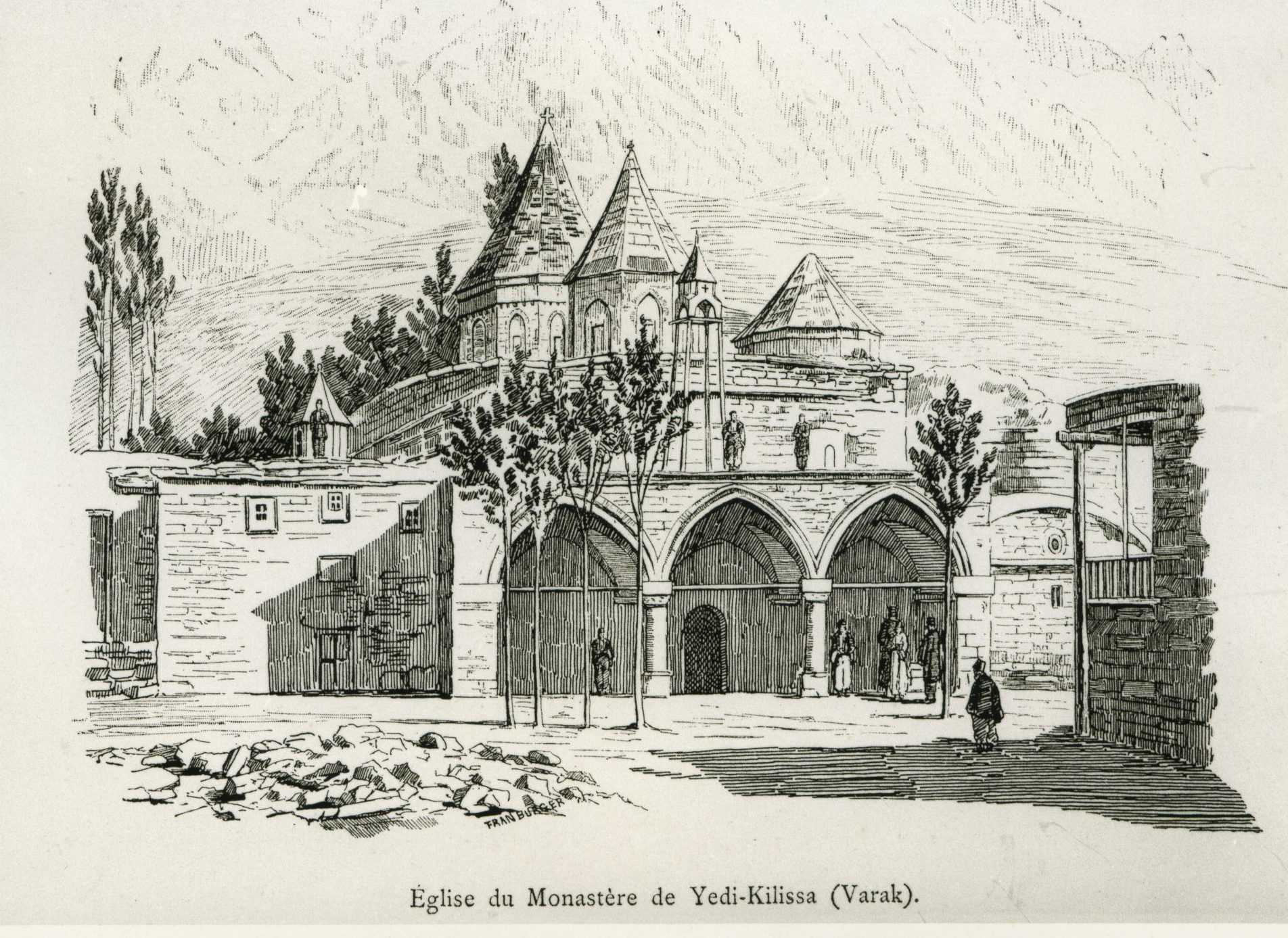

Varagavank – Վարագավանք / Varakavank / Yedi Kilise

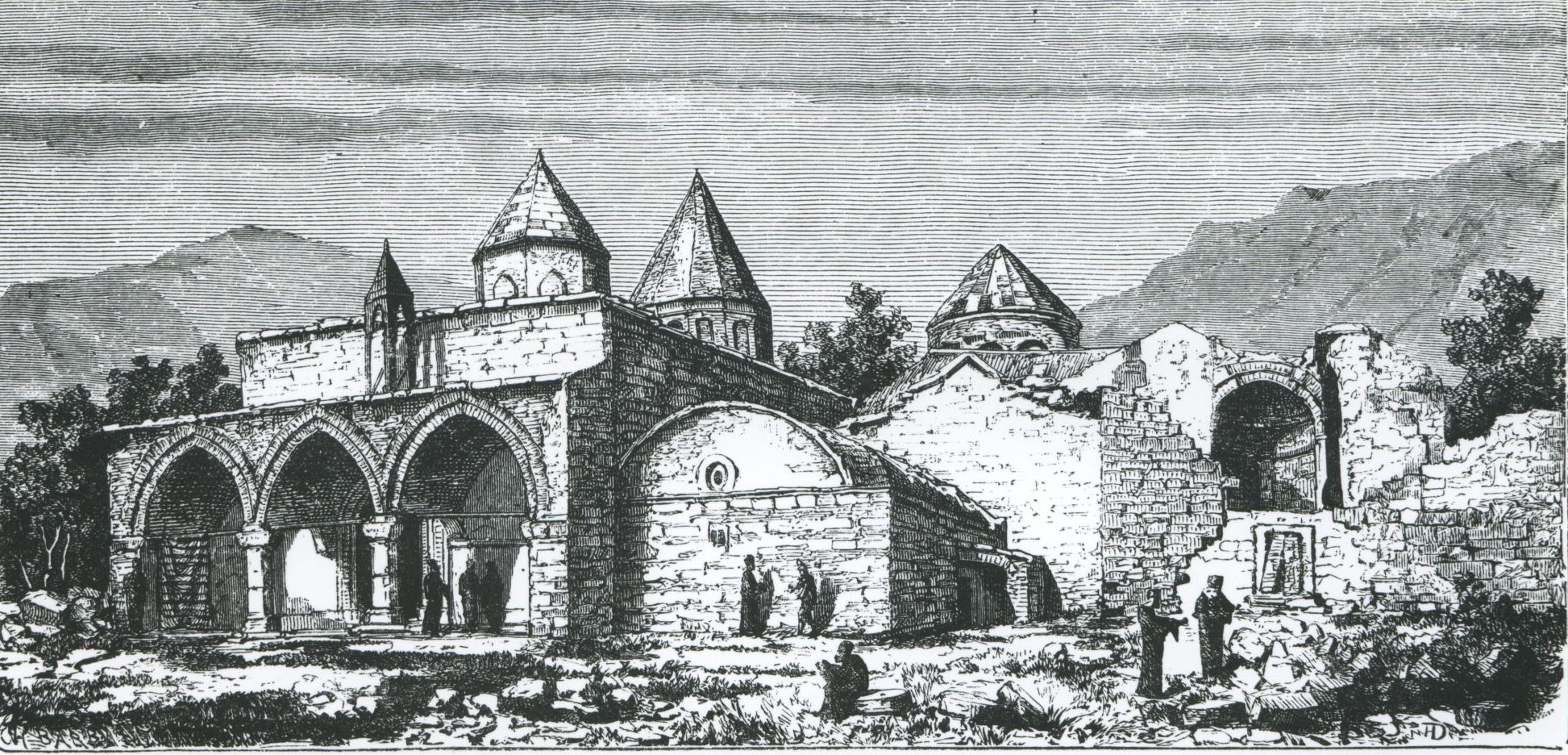

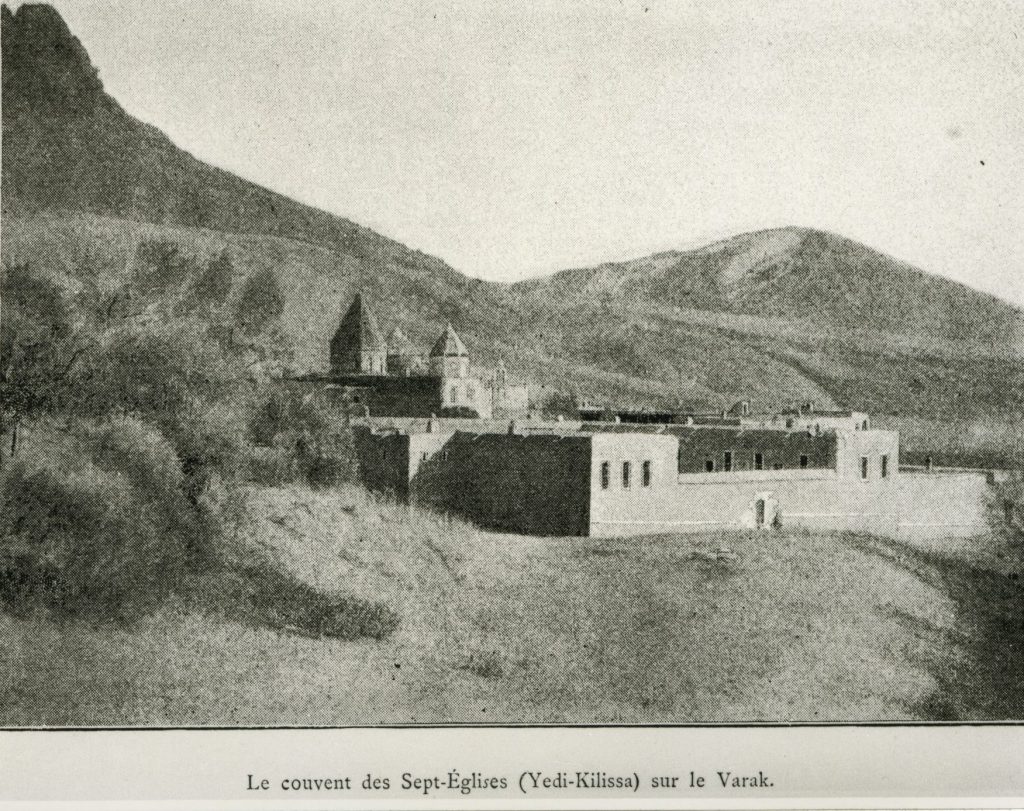

In the east of Lake Van and only nine kilometres northeast of the city of Van, at the foot of Mount Varag (Erek; 3,200 m), stood the fortified monastery named after the mountain. For over a thousand years, it has been one of Vaspurakan’s most important spiritual centres.

The Turkish place name Yedi Kilise refers to the six churches and one narthex that made up the monastery in modern times. Its history reflects the eventful fate of Vaspurakan, which was marked by numerous and devastating wars, conquests, looting and natural disasters. It is also closely linked with the cult of the Holy Cross that developed early in Vaspurakan. According to tradition, the saints Gayane and Hripsime travelled the area in the late third century A.D. during their flight from the Roman realms, bringing a fragment of the True Cross to Van.

The expansion into a grand monastery took place after the liberation from Arab rule or under the rule of the Artsruni as kings over Vaspurakan.

Queen Khushush (also Khoshush), the daughter of King Gagik I of Armenia and spouse of Senekerim-Hovhannes Artsruni, the future and last King of Vaspurakan, donated a church at the site in 981 dedicated to the Holy Wisdom (Sophia; in Armenian: Surb Sopia). The monastery itself was founded by Senekerim-Hovhannes early in his reign (1003–24) to house the relic of the True Cross that had been kept on the site since Hripsime. The Church of Surb Hovhannes (Saint John) was built to the north in the 10th century.

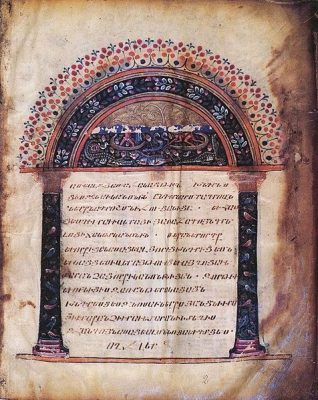

Armenian noble women played a special role as generous donors not only in the history of Varagavank Monastery. As early as 862, Queen Mlk’e, the wife of King Gagik I, donated a richly illuminated gospel to this convent, which is one of the earliest and most valuable examples of medieval Armenian book illumination. Other treasures from the monastery’s former collection, which survive in the Yerevan Matenadaran manuscript collection, date from the High and Late Middle Ages (15th-17th centuries) and document the regional characteristics of the Vaspurakan painting school. However, most of the irreplaceable monastery collection of Varagavank went up in flames in 1915.

In 1021, when Vaspurakan fell to Byzantine rule, King Senekerim-Hovhannes took the relic to Sebastia (Sivas), where the following year his son Atom founded the Monastery of the Holy Sign (Surb Nshan). In 1025, following his death, Senekerim-Hovhannes was buried at Varagavank and the True Cross was returned to the monastery. Fearing an attack by Muslims, Varagavank Father Ghukas took the True Cross in 1237 to the Tavush region of northeastern Armenia. There he settled in the Anapat monastery, which was renamed Nor Varagavank (New Varagavank). In 1313, the Mongols invaded the region and ransacked the monastery. All the churches were destroyed except St. Hovhannes, which had an iron door, behind which the monks hid. Between 1320 and the 1350s, the monastery was completely restored.

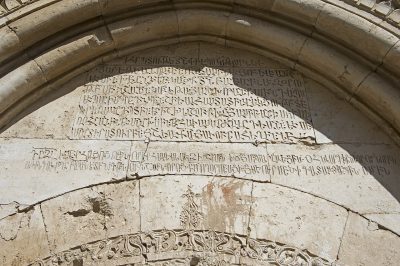

However, the Safavid emperor Tahmasp I (1524-1576) ransacked the monastery again in 1534. In 1648, along with other buildings in the region, an earthquake destroyed Varagavank. Its restoration began immediately thereafter by monastery father Kirakos who found financial support among the wealthy merchants of Van. According to the 17th-century historian Arakel of Tabriz, four churches were restored and renovated. During this period of extensive conservations and extensions, the architect Tiratur built a square-planned gavit (narthex) west of Church of Surb Astvatsatsin (Holy Mother of God) in 1648. It functioned as a church during the 19th century, dedicated to Saint George (Surb Gevorg). To the west of the narthex was a 17th-century three-arched open-air porch; to the north was the Church of the Holy Cross (Surb Khach), while to the south was the 17th-century Church of Surb Sion. Urartian cuneiform inscriptions were used as lintels on the western entrances of these churches.

Only a few years later Süleyman, the prince of Hoşap Fort, invaded the monastery in 1651, looting it of its Holy Cross, manuscripts, and treasures. The theft of relics, including manuscripts revered as relics, and the blackmailing of Christian communities to buy the return at high prices was common practice among Ottoman Muslims. The True Cross of Varagavank was later repurchased and it was added to the Tiramayr Church of Van in 1655 (according to ‘Virtual Ani’ the cross relic was preserved in the Surb Nshan Church inside the walled Old City of Van), but lost during the siege and massacres of 1915.

The monastery declined in the late 17th century and, in 1679, many of its treasures were sold due to economic hardship. Archbishop Bardughimeos Shushanetsi (Bartolomew of Shushan) renovated the monastery in 1724. In 1779, the archimandrite (vardapet) Baghdasar decorated the narthex walls with frescoes of King Abgar V, Theodosios I, Saint Gayane, Hripsime, Khosrovidukht, and Gabriel that blend the styles of Armenian, Persian, and Western European art.

The 19th century brought further decline, intermitted by survival.

A wall was built around the monastery in 1803. In 1817, the completely renovated Church of Surb Khach (Holy Cross) was converted into a depository of manuscripts (matenadaran) by archbishop Galust. However, despite the convent’s fortification, Tamur, the ruler of Van robbed the monastery’s treasures and strangled the archimandrite Mkrtich Gaghatatsi to death in 1832.

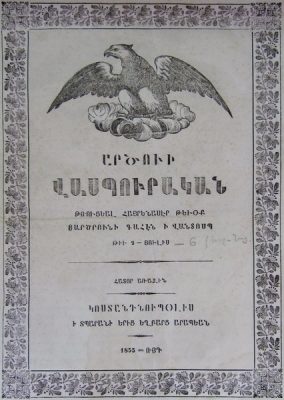

Mkrtich Khrimian (1820-1907), the future Catholicos Mkrtich I (Vanetsi) of the Armenian Church, became abbot of Varagavank in 1856 (until 1862) and made the monastery effectively independent from the Catholicate of Vaspurakan and subordinate only to the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople. He founded a printing house and began publishing the weekly journal Artsvi Vaspurakan (“The Eagle of Vaspurakan”; 1855-1874), the first newspaper in historical Armenia. He also established a modern boarding school where theology, music, grammar, geography, Armenian studies and history was taught. The Iran born novelist Raffi (1835–1888, i.e. Hakob Melik-Hakobian) was briefly one of the teachers (cf. contribution by Ashot Hayruni: – Author of the Armenian National Revival); the author mentioned Varagavank in the two volumes of his novel Sparks («Կայծեր», 1883-87). But such revivalist activities also increased the existing suspicions of the regional and central Ottoman authorities. During the Hamidian massacres of 1896, the monastery was sacked again and robbed, its school destroyed. Some teachers and students were killed. According to a contemporary report by an American at Van, “Varag, the most famous and historic monastery in all this [Van] region, which has weathered the storms of centuries is almost certain to go [on fire].”

The school, however, was re-established and had over a hundred resident pupils in 1913.

On 20 April 1915, some 30 gendarmes arrived at the monastery and murdered its last two monks, the Fathers Aristakes and Vrtanes, together with four of their servants. The monastery remained under the gendarmes’ occupation until 30 April, when, for unknown reasons, they withdrew to Van city. This coincided with the arrival on Varag Mountain of some 3,000 Armenian refugees from the Hayots Dzor valley who had escaped the massacres that had taken place there several days earlier. Some 3,000 survivors of massacres elsewhere soon joined them, and together they found a temporary refuge in the Armenian villages and monasteries on Mount Varag, including Varagavank. Self-defense units were also set up in an attempt to protect the villages – about 250 men, almost half the force, was stationed at Varagavank, with most of the remainder based at nearby Shushants monastery and village (pop. 559). On the order of vali Cevdet, Ottoman forces returned in strength, with a force of 300 cavalrymen, 1,000 militia, and 3 batteries of artillery. Shushants quickly fell after putting up a feeble defense and was burnt down. Varagavank fell shortly afterwards. The majority of the villagers and the refugees managed to escape to Van at night. The Ottoman forces did not attempt to stop them entering the Armenian-controlled sectors of the suburbs of Van, obviously with the intent that the refugees would use up the limited food supplies of the defenders.

Varagavank was destroyed by Ottoman forces sometime between 30 April and 8 May 1915 during the siege of Van. A Kurdish village, called Bakraçlı, later grew up around the ruins of the surviving churches.

The exact date of the burning of the monastery is not known. While Elizabeth Barrows Ussher noted in her diary that Varagavank was attacked by 200 cavalry and foot soldiers on 30 April 1915, but repulsed, her husband Clarence Douglas Ussher and the American missionaries Ernest Alfred Yarrow and Grace H. Knapp mentioned 27 April and 4 May 1915, respectively, as the day when Shushants and Varagavank were set ablaze.

Most of the surviving structures were destroyed in the 1960s. In 1998, the stones of the monastery served as building material for the construction of a mosque in the same place. Today, the best-preserved section is the Church of St. George (Surb Gevorg) with its partly collapsed dome, whereas the dome of the Surb Nshan Church is entirely gone. In February 2010, following the renovation of the Cathedral Surb Nshan at Aghtamar in Lake Van, Halil Berk, the Deputy Governor of Van Province, announced that the Governor’s Office sought to restore Varagavank and the Ktuts monastery (dating back to the 5th century) at Çarpanak Island. In June of that year, the governor also stated that the two monasteries would be renovated “in the near future.” However, nothing happened. In 2011 an earthquake did further damage to the surviving ruins. In August 2017, Ali Kalchek, the Head of the Van Monuments Protection Union, told the mass media: «The church is being regularly destroyed to use its stones to build a mosque, houses in neighboring villages and other constructions. The temple is on the verge of destruction.»(1)

Raffi – Author of the Armenian National Revival

The popular literature that Raffi had been advocating since the 1860s and that appealed to the widest possible strata of society and was generally comprehensible should not only reflect real life, but also contain proposals for solutions to the social and national problems presented. Raffi demanded that an author, as a “representative of his time”, should lead and form opinions.

As a writer, Raffi has realized this program, which was initially propagated by the media. Under the immediate impression of the Russian victory over Turkey in 1878, which fed many Armenians the hope of their liberation from the extremely oppressed situation in Turkey, Raffi wrote the time novels Čalaleddin (1878), Xentẹ (The Madman, 1881) and Kaycer (Sparks, vol. 1-2, 1883-7) as well as the historical novels Davit’ Bek (1882), Parowyr Haykazn (1884) and Samvel (1886). The time novels, based on Raffi’s personal view of rural life in Turkish Armenia, describe the double oppression of the peasantry by Turks and Kurds and their paralyzing spiritual, social and psychological consequences. As in the contemporary Russian prose of the narodniki, numerous conflicts result from the fact that the Armenian national revolutionaries, struggling for emancipation, liberation, spiritual and political renewal, remain alien to their compatriots. Dudukč’yan is the misunderstood and therefore by the villagers declared crazy title hero from Raffi’s best-known novel Xentẹ (1880). The army commander Davit’ Bek, title hero of Raffi’s first historical novel, led the anti-Persian resistance in the Armenian region of Syunik until his death in 1728. In the following two novels Raffi turns to protagonists in transitional periods or extreme situations: The poor sophist Parowyr Haykazn (276-368), known to the Greeks as Proairesios, taught rhetorics in Athens and Rome, including the church father Basileios, and was also appreciated by Emperor Constantine. The plot of Samvel takes place in the late 4th century during the liberation struggle against the Sasanids. The patriotic protagonist, Prince Samvel Mamikonean, fights against his own relatives and in the end kills father and mother because they collaborate with the Persians or have converted to Zoroastrianism. Raffi’s contemporaries read the novel as an encoded message about the escalating conflict between the Armenian national independence movement and the Russian tsarist empire, whose censorship authority suppressed a dramatization of the novel; a stage version in French (‘Samuel’) was published in 2005.

According to Raffi, the writer should resemble a doctor who not only diagnoses the diseases correctly, but also prescribes the appropriate therapy. Diagnosis and therapy, however, require knowledge of the origin and course of diseases. A writer must therefore familiarize himself with the history of a people in order to fulfil the role mentioned above: “Our present is the continuation of the past. The causes and roots of current diseases must be sought in the past”. History appeared to Raffi as a school in which future generations should educate themselves to avoid the mistakes of their ancestors and follow their good deeds. In order to fulfil this educational task, a historical novel does not focus on the “factual” truth, but on the “ideal” truth. In contrast to a historian, a novelist should therefore be a creator and not a mere copyist.

Raffi’s six contemporary and historical novels contain a mixture of romantic and realistic elements, depending on their purpose and subject matter. They make up the most important contribution to Armenia’s national revival literature, whose role models and guiding principles inspired generations of Armenians. The vision of the future of the main hero Vardan, with which the best-known novel, Xentẹ, ends, was laid down in the programs of the social revolutionary parties founded shortly after its publication: a united, free and independent Armenia with representative government and associated key industries, populated by educated, self-confident citizens. The popular literature that Raffi had been advocating since the 1860s and that appealed to the widest possible strata of society and was generally comprehensible should not only reflect real life, but also contain proposals for solutions to the social and national problems presented.

©Ashot Hayruni (Yerevan)

The Churches of Varagavank

The main church, the church of the Holy Mother of God, (3), was perhaps built by Senekerim, although if that is the case then it was substantially rebuild during later periods (especially after an earthquake in 1648).

The main church, the church of the Holy Mother of God, (3), was perhaps built by Senekerim, although if that is the case then it was substantially rebuild during later periods (especially after an earthquake in 1648).

It has a plan that is sometimes called a “St. Hrip’sime type”, named after the 7th century church of St. Hrip’sime at Echmiadzin, the first dated example of this sort of plan. It is also known as a “four-apse, four-niche” plan. Its characteristic feature are the four, nearly circular, “niches” that are set into the masonry between the apses and the corner rooms.

The walls are surprisingly crudely built: rubble masonry behind a thick layer of plaster. The vaults, with pointed arches, and upper part of the walls are of brick. There was a dome over the central space. This was also built of brick and was supported by a brick drum, cylindrical inside and dodecagonal outside.

Adjoining the north wall of the main church was a smaller building known as the Church of the Holy Seal, (5). Nothing of it now survives.

West of the Church of the Holy Mother of God is a large hall, (4), called a zhamatun in Armenian. An inscription over its door records that it was built in 1648 by the architect Tiratur. It probably replaced an older structure destroyed in the earthquake of that year. It is a square structure, 14 by 14 metres, built of well cut stone, and divided into 9 bays. The roof over the centre bay had a dome over a tall, octagonal drum. The roofs over the other eight bays have domed vaults resting on pendentives. The doorway from the zhamatun into the church is particularly ornately decorated, using a mixture of Armenian, Turkish, and Persian motifs.

The free-standing and engaged pillars inside the zhamatun have frescoes depicting, amongst others, St. Hrip’sime, St. Gayane, the archangels Michael  and Gabriel, various other saints, clerical figures, and the patron of the zhamatun, Kirakos. These frescoes, today in very bad condition, were once garishly coloured. The British traveller and diplomat A. H. Layard, after a visit in 1850, wrote “Its walls are covered with pictures as primitive in design as execution. There is a victorious St. George blowing out the brains of a formidable dragon with a bright brass blunderbuss, and saints, attired in the traditionary garments of Europe, performing extravagant miracles”. The frescoes are thought, on stylistic grounds, to have been painted by an Armenian from Persia.

and Gabriel, various other saints, clerical figures, and the patron of the zhamatun, Kirakos. These frescoes, today in very bad condition, were once garishly coloured. The British traveller and diplomat A. H. Layard, after a visit in 1850, wrote “Its walls are covered with pictures as primitive in design as execution. There is a victorious St. George blowing out the brains of a formidable dragon with a bright brass blunderbuss, and saints, attired in the traditionary garments of Europe, performing extravagant miracles”. The frescoes are thought, on stylistic grounds, to have been painted by an Armenian from Persia.

Against the north wall of the zhamatun is another chapel, (6), the church of the Holy Cross. It was built (or rebuilt) in 1817, and served for a while as the monastery library. Built against the south wall of the zhamatun is a barrel vaulted room, (7), built in 1849. Although it is not particularly church-like, it was known as the church of St. Sion.

An arched porch stands in front of the west wall of the zhamatun. Above its central bay was a two-storey belltower. This entrance porch once looked out onto a courtyard that was surrounded by ancillary buildings belonging to the monastery.

To the south of the main monastery complex were two churches. At least one was older than the date of Senekerim’s foundation of the monastery. The southernmost church, (1), St. Sophia, was commissioned by Khoshush, the daughter of King Gagik I of Ani and the wife of Senekerim, future king of Vaspurakan, and built in the year 981. Its plan was a domed-hall type. It collapsed in an earthquake in 1648 and was not rebuilt. Only the apse now survives, used as a shelter for hay. The church of St. John, (2), was built against the north wall of St. Sophia. Both churches were very similar in their style of construction and so were probably from the same period. St. John was a three apsed church, with a dome supported by a cylindrical drum that res

ted on squinches. It was intact before 1915 but is now entirely destroyed.

“Virtual Ani”:http://www.virtualani.org/varagavank/

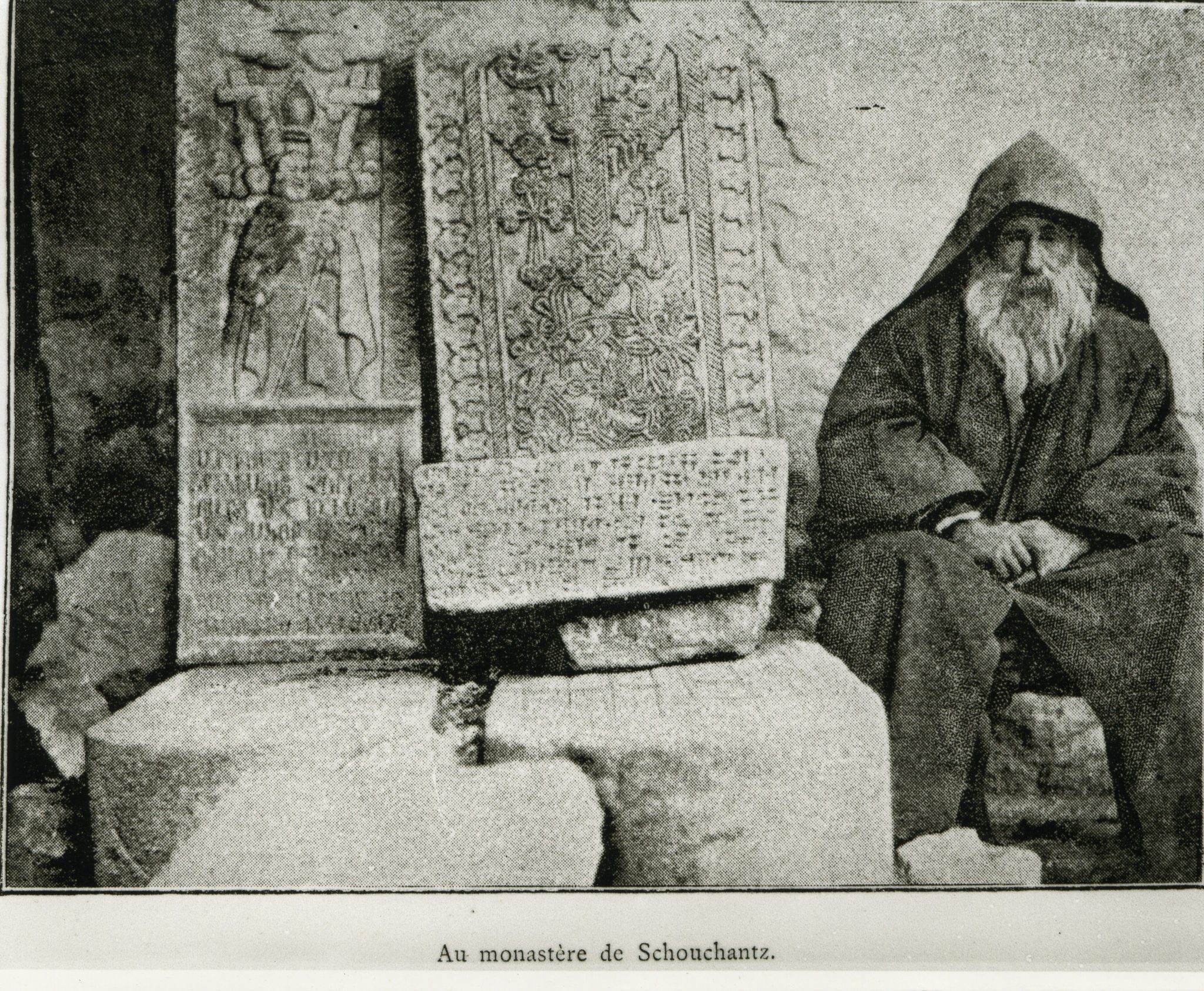

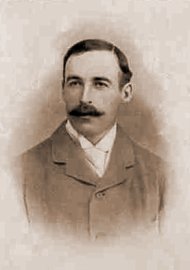

Lynch, H.F.B.: Visit to Varagavank (Yedi Kilise) Monastery in 1893

Lynch, H.F.B.: Visit to Varagavank (Yedi Kilise) Monastery in 1893

“A cloud of unusual gloom enveloped the destinies of the ancient place; and one might doubt whether the gentle Daniel had ever experienced so many calamities during the thirty-five years which he had passed within these walls. The most severely felt of all the blows which the Turkish Government had been raining upon them was the loss of their printing press. Some short while back the officials appeared and walked off with the precious instrument, of which the voice had been mute for many years. They erected it in Van, and, having kidnapped an Armenian compositor, used it to publish an official gazette. In company with the Mudir I had happened to pass the building where it was lodged; and my companion remarked to me that he was looking forward to obtaining some money for his schools with the proceeds of the sale of the paper.

The site of the monastery is a dip or pass upon the outline of gentle hills which stretch from the more southerly slopes of the mountain to confine the plain upon the south. From its windows only a vista of the lake is obtained. The church consists of a larger pronaos with the usual conical dome, communicating on the east by a richly moulded and spacious doorway with a chapel or sanctuary. The interior of this chapel recalls features in St. Ripsime at Edgmiatsin. It has four apses or recesses, one on each wall, separated from one another by deep niches. The whole is surmounted by a conical dome (Fig 137). In the floor of the pronaos are seen three stone slabs with inscriptions. They cover the remains of King Senekerim, of the Armenian medieval dynasty, his queen Khoshkhosh and the Catholicos Petros. The frame of an altar erected upon the site of these slabs has been stripped of all its ornaments. This act appears to have been committed by the Hayrik, and out of anger against Senekerim. The mild features of Daniel Vardapet contracted as we spoke of that monarch; and he assured me with some vehemence that he would dig out his bones and cast them on the rocks were it not for his title of king of Armenia. The chapel of Yedi Kilisa is most interesting to the student of architecture, and is no doubt a work of considerable antiquity. A ruined chapel on the south of the building contains a much-effaced inscription to the effect that it was constructed by the lady Khoshkhosh, daughter of Gagik and queen of Senekerim.“

Source: Lynch, H.F.B.: Armenia: Travels and Studies. Vol. II: The Turkish Provinces. (Reprint). Beirut: Hayats, (1990), p. 114f.