Population

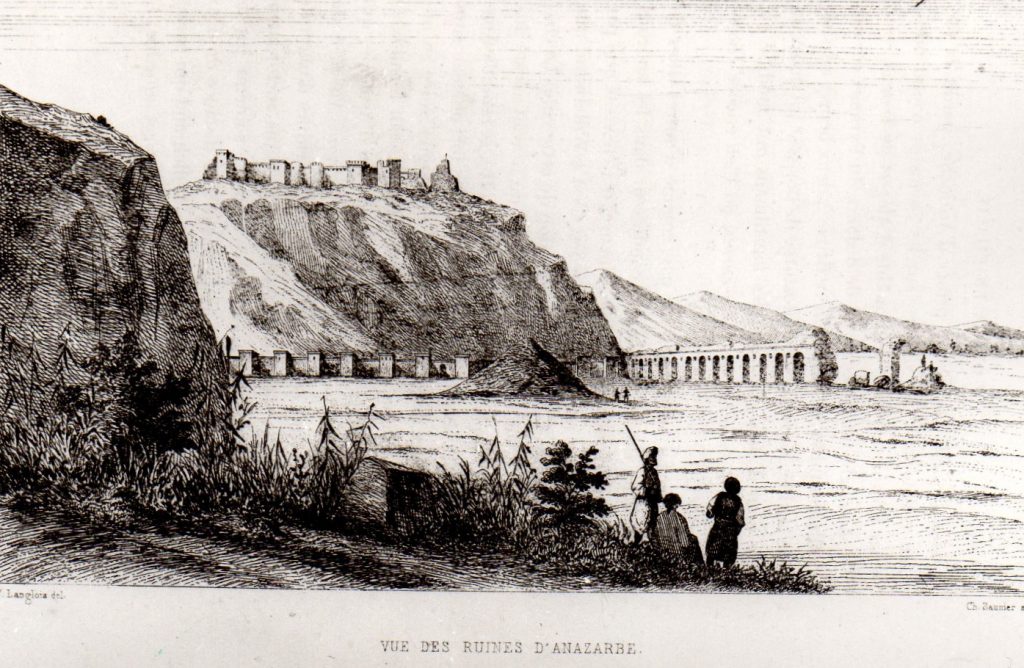

At the turn of the twentieth century, in the kaza’s seat, Sis, about 5,600 of the population of 8,000 were Armenians.[1] “In the rest of the kaza of Sis were a dozen Armenian villages, of which the most import were Karacalın and Gedik. In the ancient capital of the Rupinian [Rubinian] dynasty, Anavarza, which lay 30 kilometers further to the south, one could still see traces of the extraordinary fortress built on a rocky outcrop towering over the plain, which was covered with Greco-Roman ruins.”[2]

Town of Sis / Kozan

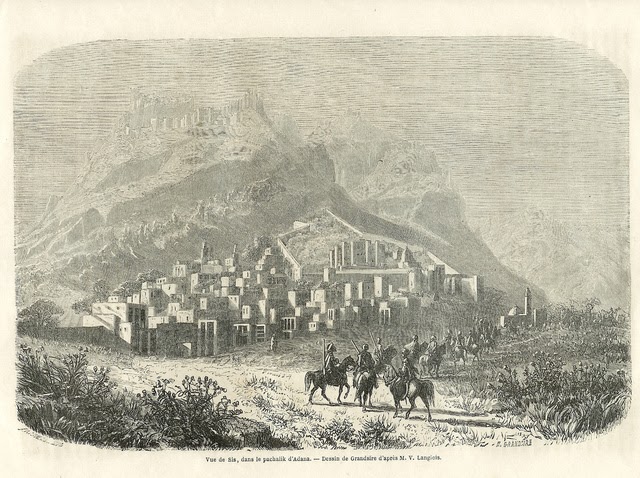

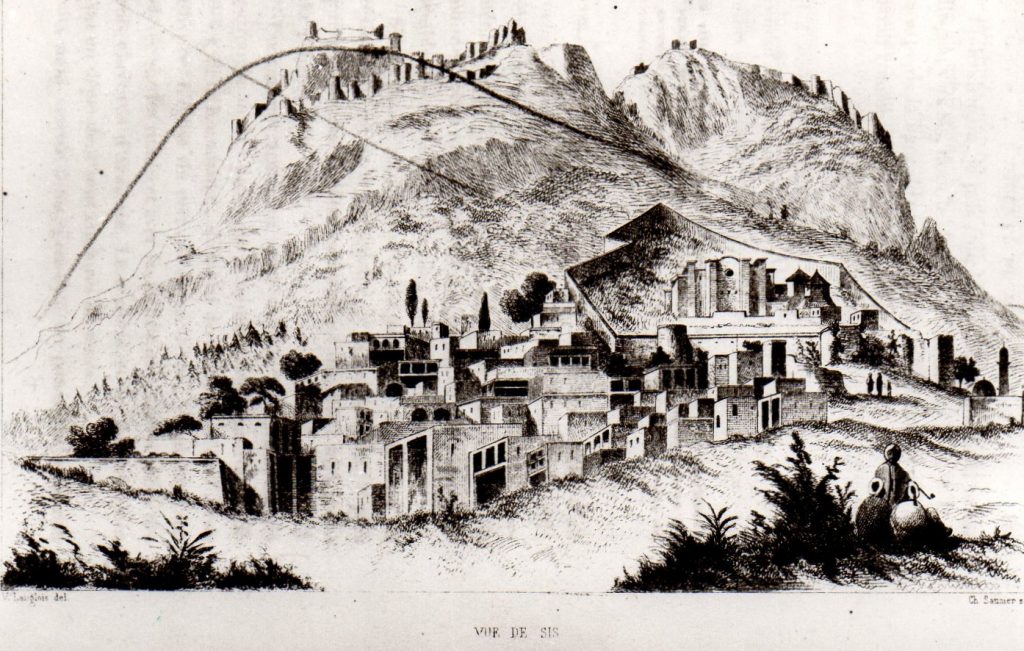

The historical capital and administrative seat Sis, now called Kozan, was built on a long rocky ridge in the center of the modern city. Situated in the northern section of the Çukurova plain, Sis (Kozan) was the capital of the Ottoman sancak of Kozan and of the kaza of Sis. The Kilgen River, a tributary of the Ceyhan, flows through the town and crosses the plain south into the Mediterranean. The Taurus Mountains rise up sharply behind the town.

For the first time Sis was mentioned in 964, when the Byzantine emperor Nikephoros’ II Phokas completed the conquest of Cilicia. From the mid-12th century to 1375 Sis was the capital of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and from 1293 the spiritual center of the Holy See of Cilicia (Great House of Cilicia), which since 1930 had to be resettled to the Lebanese town of Antelias near Beirut.

Toponym

The Armenian place name Sis derives from “mountain”. Under the Roman Empire, Sis was Flavias or Flaviopolis in the Roman province of Cilicia Secunda.

Population

“The ancient capital of the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia and the official residence of the catholicos, [Sis] formed a monumental architectural ensemble. Overlooking the town at the dawn of the twentieth century was the royal citadel, surrounded by a colossal wall with 44 towers. In 1914, Sis was still three-quarter Armenian, with an Armenian population of 5,600 out of a total population of nearly 8,000, and it still clearly preserved its medieval character.”[3]

History

In 704, Sis was besieged by the Arabs, but relieved by the Byzantines. The Abbasid caliph al-Mutawakkil took it and refortified it, but it soon returned to Byzantine hands.

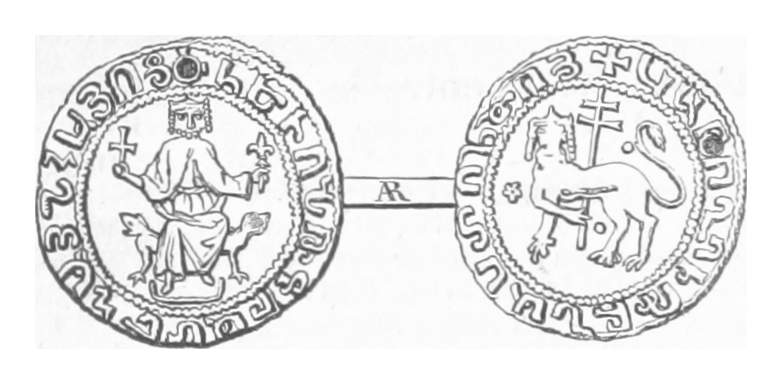

At the beginning of his reign, T(h)oros I Rubinian (r. 1100-1123), prince of Cilicia, with the support of local Armenians, liberated Sis from Byzantine rule and restored the Drazark monastery nearby, turning it into the Cilician mausoleum of the Rubenians’ dynasty and an eductional center. In Drazark was also a bishop’s residence of the capital Sis.

The earthquake of 13 November 1114 severely damaged Sis, killing many residents. Prince Mleh Rubinian (r. 1169-1174) rebuilt Sis in 1173 and declared it the capital of Cilician Armenia. The town was thoroughly rebuilt and fenced, with a royal palace, secular and religious buildings, gardens and flower gardens, enriched by Levon II the Great (as King Levon I).

Construction in Sis continued during the reign of King Het(h)um I and his successors. Armenian historians especially praise the new palace and its magnificent sculptures founded by Hetum I in the northern district of the city. The three-walled, three-gate fortress with strong towers is divided into three parts, which are connected by stone paths. On the southern side of the fort is the inner fortress or the castle itself, where the court was sheltered in times of danger.

Sis had several dozen churches and monasteries. The old episcopate and its three-altar Church of Surb Grigor Lusavorich (Gregory the Illuminator) was located on the southern outskirts of the city. After the conquest of Hromkla (‘Roman’, i.e. ‘Byzantine’ or ‘Greek Fortress; Trk.: Rumkale) in 1293 by the Mamluks, Sis became the seat of the All-Armenian General Catholicate, and later the seat of the regional Armenian Catholicate of Cilicia (Great House of Cilicia).

One of the charitable institutions of Sis was the hospital of Queen Zapel. Sis was the largest center of pan-Armenian culture, where by the choice of the court, the leading intellectuals collected, studied, copied, and saved thousands of old manuscripts, valuable scientific and literary works. The selected manuscripts of Sis were mainly kept in the royal Matenadaran (‘scriptory’). Sis was famous for its specialized high schools, the most famous of which was the secular university founded by the Armenian archbishop of Tarsus, Nerses Lambronatsi (1153-1198), who belonged to the royal Het(h)umid dynasty.

The Fall of Sis

In August 1266, Baibars, the Sultan of the Egyptian Mamluks invaded Cilicia with a great force, besieged Sis, but failing to capture the fortress, destroyed and burned the city, plundering the treasures. Near the city walls the Armenian army, led by the diplomat, judge and military commander Smbat Sparapet (Armenian: Սմբատ Սպարապետ, Սմբատ Գունդստաբլ, Smbat Sparapet, Smbat Gúndestabl; 1208–1276), defeated the invaders and threw them back. In the 1270s the city was rebuilt, the walls were fortified. In 1275, the troops of the Sultanate of Egypt again tried in vain to capture Sis. For about a century Sis lived a relatively peaceful life. During the Crusade the Holy See of the Armenian Apostolic Catholicate returned to Sis in 1294, and remained there for 150 years.

Then the army of 60,000 of the Sultanate of Egypt again besieged Sis again in 1369. Although burning down the city and looting it, the enemy was nevertheless forced to leave the fortress and retreat. Taking advantage of the weakening of state power and internal divisions in Cilician Armenia, the Ramadanids, under the flag of the Mamluke Sultan of Egypt, Malik al-Ashraf, in 1375 demolished the city, besieged for three months the fortress and captured it, arrested King Levon VI and a number of princes. Armenian historians assessed the fall of Sis as the final loss of Armenian statehood. As a reaction to escalating violence, many residents migrated to foreign countries.

The town never recovered its prosperity. In 1516, it passed into the power of the Ottomans.

Ecclesiastical history

Sis had an important place in ecclesiastical history both of the Armenian Apostolic Church and as a Roman Catholic titular see.

In the Middle Ages, Sis was the religious center of Christian Armenians since 1293 until 1441, when the Armenians moved the seat of Catholicos back to Vagharshapat (Echmiadzin), in Armenia.

Even prior to the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, Sis was an episcopal see and several names of bishops and patriarchs can be found in the literature:

- Alexander, later Bishop of Jerusalem and founder of the famous library of the Holy Sepulchre in the third century

- Nicetas, present at the First Council of Nicaea in 325

- John, who lived in 451;

- Andrew in the sixth century

- George (681)

- Eustratus, Patriarch of Antioch about 868

When in 1441 a synod decided to transfer the Catholicate back from the Cilician capital of Sis, by then conquered by the Mamelukes, to the Eastern Armenian town of Echmiadzin (Vagharshapat), the then incumbent catholicos Grigor IX refused to move. On Grigor’s refusal the Armenian clergy installed a rival, namely Kirakos I Virapetsi (Kirakos of Armenia) at Echmiadzin, who, as soon as the Ottoman sultan Selim I had conquered Greater Armenia, became the more widely accepted of the two by the Armenian church in the Ottoman Empire.

The Catholicos of the Holy See of Cilicia maintained himself nevertheless, with under his jurisdiction several bishops, numerous villages and convents, and was supported in his views by the Roman Catholic Pope up to the middle of the 19th century, when the patriarch Nerses V Ashtaraketsi, declaring finally for Echmiadzin, carried the government with him. In 1885, Sis tried to declare the catholicate at Echmiadzin schismatic, and in 1895 the clergy of Sis took it on themselves to elect a Catholicos; but the Ottoman government annulled the election, and only allowed it six years later upon Sis renouncing its pretensions to independence. The Catholicos of Sis had the right to prepare the sacred myron (oil) and to preside over a synod, but was in fact not more than a metropolitan, and regarded by many Armenians as schismatic.

The “double-headedness” of the Armenian Apostolic church and the struggle between Echmiadzin and Sis or Antelias (Lebanon), where the seat of the High House of Cilicia has been located since 1930, was settled in April 1995 with the election of the previous “Cilician” church leader Garegin II as “Catholicos of all Armenians,” who, together with his predecessor Vazgen I, had been striving since 1963 to reconcile the two particular churches. About half of the Armenian Apostolic dioceses, prelacies and churches in the USA, the complete Middle Eastern dioceses of Beirut, Aleppo, Damascus and Nicosia, the dioceses of Iran and parts of the diocese of Athens continue to be under the “Holy See of Cilicia”.

Destruction

During the Adana massacres of April 1909, the Armenian population of the towns of Sis and Hadjin had successfully defended themselves.

„After overseeing the task of disarming and deporting the Armenians of Hacın, Colonel Hüseyin Avni attacked the Armenians of Sis and the kaza of Kozan. On 2 May 1915, the mutesarif, Safvat Bey (who had assumed office on 2 December 1914) was dismissed, probably because he was judged unreliable, and replaced the same day by Salih Bey. In Sis, the Bosnian colonel also secured the support of local state officials and notables, particularly that of Hüseyin Bey, the head of the municipality, (…) and çetes [irregulars], recruited in the area on Avni’s initiative.

The official order to deport the Armenians of sis, confirmed by the interior minister [Mehmet Talat] in person, did not reach the prefecture until 17 June 1915. As in Hacın, the inhabitants of the city and the surrounding villages were gradually expelled in the direction of Osmaniye and Aleppo. From these towns they were dispersed over the different deportation routes.”[4]

Դրազարկ / Թրազարկ – Drazark / T’razark / Աւագ վանք – Avag Vank’ / Senior Monastery

“Of all Cilician Armenian monasteries, cloisters and hermitages, Drazark (Դրազարկ, Թրազարկ) was perhaps the most important, the most famous and the most associated with the history of the Rubenian princely, later royal house, from its dawn to extinction. According to Armenian medieval sources, Drazark was founded or renewed by great ińxan (great prince) T῾oros I Rubenian (about 1100 – 29) in the first half of his reign. The earliest mention of Drazark dates back to 1113.”[5]

The monastery’s founding date is unknown (…). After the earthquake of 1114, Prince Toros I (~1100-1129) of the Rubenid Dynasty restored the monastery and added to it a mausoleum for the leadership of the Armenian Church in Cilicia and for the princely families of Armenian Cilicia, as well as an educational center. It also served as the bishop’s residence for the Cilician capital of Sis. Prince Toros I invited people to head the construction, including Gevorg Meghrik Vaspurakantsi (Armenian: Գևորգ Մեղրիկ Վասպուրականցի, George Meghrik from Vaspurakan) and Kirakos Gitnakan (Armenian: Կիրակոս Գիտնական, Kirakos the Learned). At the request of the prince, these men remained there and, between 1050 to 1121 A.D., launched an extravagant educational program, created and copied numerous manuscripts for the monks’ brotherhood, and developed regulations whereby the

monks must be occupied by reading and copying manuscripts. They edited the ‘Apostles’ Acts’ (Armenian: Գործք առաքելոց) after translating them from Greek, interpreted St. John’s Gospel (Armenian: Հովհաննեսի Ավետարան), completed the volumes Book of Feasts (Armenian: Տոնական գիրք) and Lectionary (Armenian: Ճաշոց գիրք), and translated several codices and testimonies. In 1114 after the death of Archimandrite Gevorg Meghrik, Kirakos Gitnakan was elected the monastery’s new archimandrite. Years later, Archimandrite Barseh, a person endowed with special privileges, headed the monastery, followed by Archimandrite Samuel (1178–1181). Drazark monastery’s archbishop of Sis, Hovannes (1198-1219), attended the coronation of King Levon I. Many notable personalities of the time thrived in Drazark monastery, such as Vardan Aygektsi, Arakel Hnazandents, Barsegh Gitnavor, and Konstantin Lambronatsi, in whose time the monastery became a target for enemies (1305).

Drazark monastery was famed for its high level of education in music and languages, though it always encouraged overall development in its pupils. Toros P’ilisop’a (the Philosopher) and Hovsep Yerazhisht headed the monastic musicians, and various masters of medieval written language studied within the monastery’s walls, including Hovhannes Arqayeghbayr (1220–1289, Bishop John of Sis, younger

brother of King Hetum I), as well as the scribe and notable book laminator Sargis Pitsak. The monastery also trained diplomats for the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, such as Toros the Philosopher, who was subsequently a statesman and ambassador of Cilician Armenia at the time of Levon II (1269–89) and Hetum II (1289–1307) to the kingdom of England. The monastery of Drazark continued to function even after the demise of Cilician Armenia and during the dark period of the Seljukid and Ottoman rule over Cilician Armenians during the next centuries. At the time of the Cilician Massacre in 1909, Turks plundered the monastery and murdered its priests. The monastery ceased to exist entirely a few years later during the Armenian genocide (1914-1923), sharing the fate of millions of Armenians who fell victim to Turks.

People buried in the monastic cemetery

- T(h)oros I, Prince of Armenia

- T(h)oros II, Prince of Armenia

- T(h)oros III, King of Armenia

- Ruben III, Prince of Armenia

- King Het(h)um I

- Queen Zabel / Zapel

- Catholicos Grigor IV Son

- Catholicos Grigor V K’aravehz

- Catholicos Konstantin I Bardzraberdtsi

- Catholicos Konstantin IV Lambronatsi

- Sargis Pitsak

- Gevorg Meghrik

Current condition

The remains of Drazark monastery, especially its main church of Surb Astvatzatzin (Holy Mother of God), were still known to exist in 1930, but fell from memory as the Armenian population in the area was killed or deported. In 1981 the American archaeologist Robert W. Edwards discovered the ruins of an extensive medieval monastery and one surviving church of Armenian construction, located approximately 45 km WNW of Sis (Kozan) and known today as Sara Çiçek (‘yellow flower’), which he tentatively identified as Drazark. The unexcavated church, which reveals a plan similar to the barrel-vaulted chapels of Greater Armenia, has a lower level with a conspicuous south entrance leading to a small reception area and possibly crypts.

The exact location of Drazark was established by Samvel Grigoryan in 2015. Samvel Grigoryan is the author of the first article on this topic published in May 2017. In 2015 at the Turkish village of Kibrislar, located approximately 40 km NNW of Sis, Jirair Christianian surveyed the medieval Armenian church (now converted into a mosque) and concluded very plausibly that this site was the monastic complex of Drazark. Today, only a two-story church-mausoleum remains of the extensive complex of Drazark. This structure most likely is the Holy Mother of God church, which housed in its lower floor the mausoleum where kings, queens, princes, as well as catholicoi and bishops of the church were buried. The remains of Drazark exhibit the largest surviving assemblage of medieval Armenian sculptural elements in Cilicia, including a pair of monumental khatchkars, large sculpted stone crosses mounted in the upper story ashlar masonry of the church’s west façade, and an ogee arch with framing colonnettes and bordering geometric designs. Inside the church many niches line the walls, attesting to a rich collection of relics. The expansion of the upper story church and its sculptural decorations were likely added during the reigns of King Het‛um I and his wife Queen Zapēl, or their son King Levon II and his wife Queen Keran, as both couples were devout patrons of the Church, and based on architectural parallels of the mid-13th century.

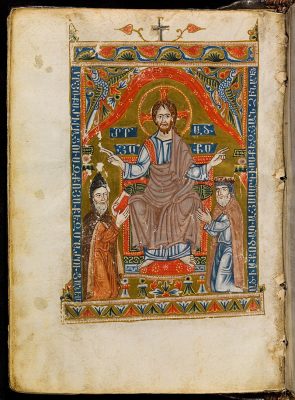

Cultural heritage from Drazark that reached our days

However, the Matenadaran institute (repository of ancient Armenian manuscripts) in Yerevan has a collection containing over 40 handwritten books made at Drazark monastery. They are written partially at a parchment and decorated by miniature paintings done by hands of medieval authors of gilded paint with wide use of Vordan Karmir. In addition some of the manuscripts that were created in Drazark stored today in Matenadaran institute under the numbers: 154, 199, 1576, 3792, 3845, 3929, 5736, 6290, 10524. There are Bibles, interpretations, motet writings, tutorials on natural sciences, the oldest copy of famous “Book of Lamentations” by Grigor Narekatsi and so on.

Excerpted from: Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Drazark_monastery