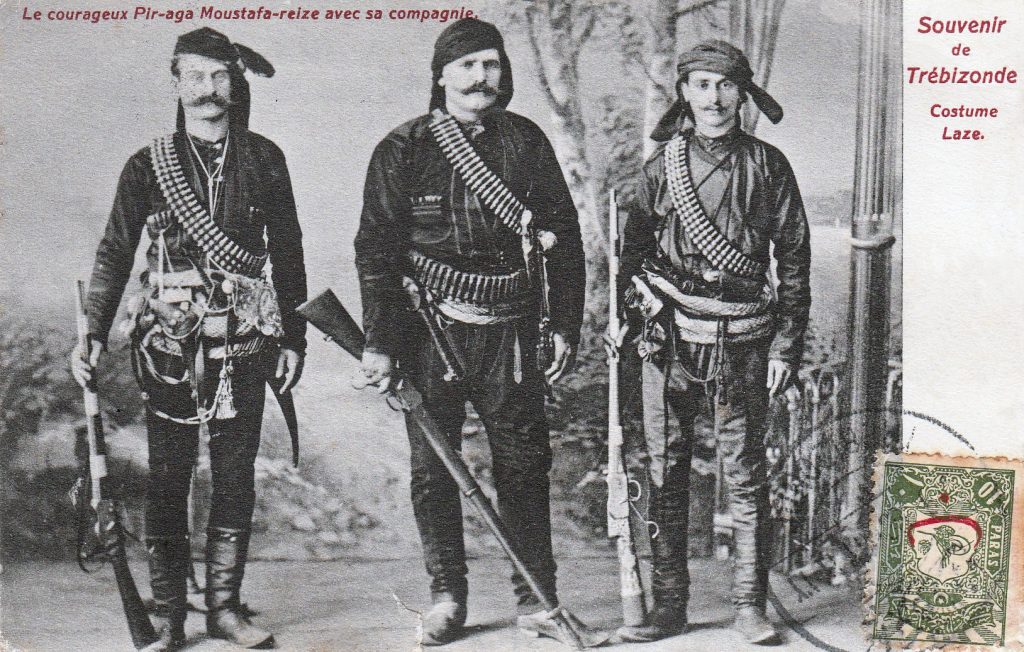

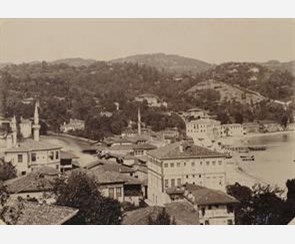

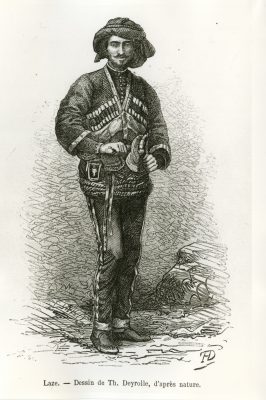

Lazistan (Laz: ლაზონა / Lazona, ლაზეთი / Lazeti, ჭანეთი / Ç’aneti; Ottoman Turkish: لازستان, Lazistān) was the Ottoman administrative name for the sancak, under Trebizond Vilayet, comprising the Laz or Lazuri-speaking population on the southeastern shore of the Black Sea.

Administrative Division

After the Ottoman conquest of the Trebizond Empire and later Ottoman invasion of Guria in 1547, the Laz populated area known as Lazia became its own distinctive area (sancak) as part of the eyalet of Trabzon, under the administration of a Governor (vali) who governed from the town of Rizaion (Rize) under the title of ‘Lazistan Mutasserif‘. The Lazistan sancak was divided into the kazas Ofi (Trk.: Of, Grk: Ofis), Rizaion (Trk.: Rize), Athena, Hopa, Gonio and Batum.

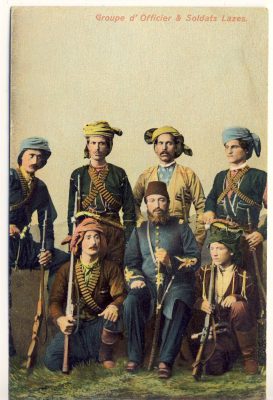

Not only the Pashas (governors) of Trebizond until the 19th century, but real authority in many of the Black Sea kazas (districts) by the mid-17th century lay in the hands of relatively independent native Laz derebeys (‘valley-lords’), or feudal chiefs who exercised absolute authority in their own districts, carried on petty warfare with each other, did not owe allegiance to a superior and never paid contributions to the Ottoman sultan. This state of insubordination was not broken until the assertion of Ottoman authority during the reforms of the Osman Nuri Bey in the 1850s.

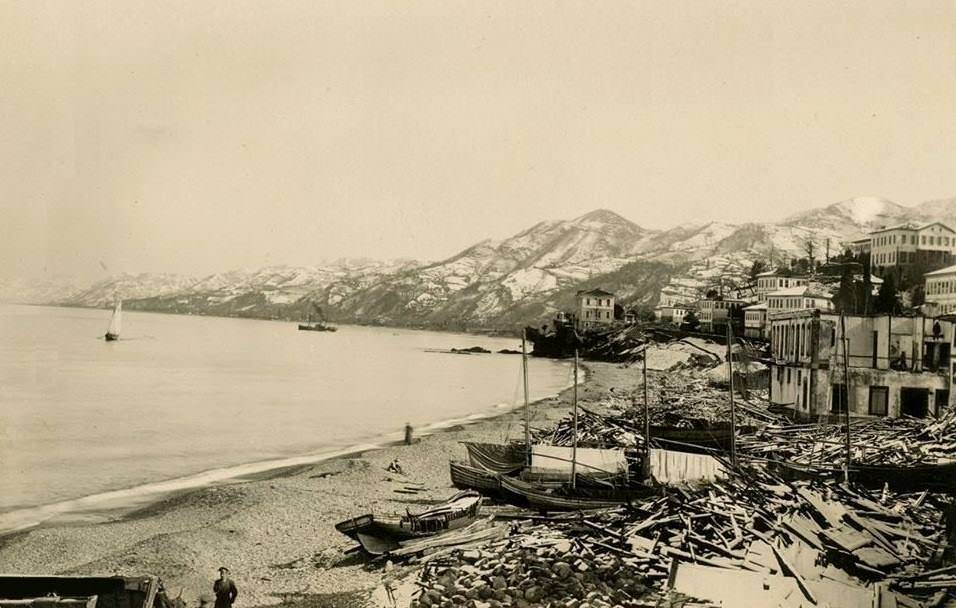

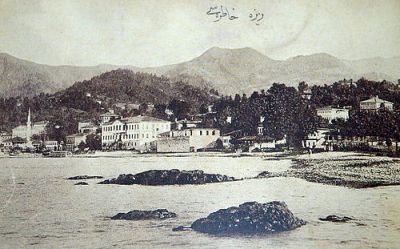

In 1547, the Ottomans acquired the coastal fortress of Gonio (Grk.: Apsaros), which served as capital of Lazistan; then Batum until it was acquired by the Russians in 1878, thereafter, Rize became the capital of the sancak. The Muslim Lazes living near the war zones in the Russia ruled Batumi Oblast were subjected to ethnic cleansing; many Lazes living in Batumi fled to the Ottoman Empire, settling along the southern Black Sea coast to the east of Samsun and Marmara regions.

Population

The Muslim population of the sancak Lazistan was made up of Sunni Muslim Laz, Turks, Islamized Armenians (Hemshin people) and Greeks.

“According to the Ottoman census of 1914, there were only 35 Armenians in the whole sancak of Rize. This statistic, however, masks a much more complex reality: the mountainous region of Hamşin [Trk.: Hemşin] was home to an Armenian-speaking population that was converted by force to Islam between 1680 and 1710, and was distinguished by conspicuous cultural traits. Despite the activity of the mutesarif, Süleyman Sami Bey (who held his post from 16 July 1914 to 16 July 1915), this population unhesitatingly took in a number of Armenians from the regions of Kiskim, Bayburt, and Erzurum, which made these mountains a locus of resistance to the government forces that set off in pursuit of the Armenian fugitives.”[1]

According to the Turkish demographer Kemal Karpat, in 1914 there lived 1,722 Greek Orthodox Christians in the three kazas of Rize, Atina and Hopa.[2]

According statistics provided by the Greek Orthodox prior of St John Monastery, Panaretos, in 1920, it can be deduced that “in the six ecclestical districts of Pontos, there were 233,400 Muslims of Greek origin. The statistical break-down of Greeks was:

- 696,495 Greek Orthodox

- 190,000 Greek Muslims

- 43,000 Greek crypto-Christians

- Total: 929,895”[3]

In his report to the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs prior Panaretos defined the territory of Pontos as “(t)he prefecture of Trebizond and certain borderline areas in the prefectures of Erzurum and Sivas, populated by Greeks”.[4]

Religion and Forced Conversions

The Ottomans fought for three centuries to destroy the Christian-Georgian consciousness of the Laz people. The execution of the Three Hundred Laz Martyrs took place on Mt. Dudikvati (‘the place of beheading’) and on Mt. Papati (‘the place of the clergy’) respectively. The beheading of some three hundred Laz warriors on a single mountain between the years 1600 and 1620 and the martyrdom of the clergy at one local monastery was what occurred during these massacres. The result was the dissolution of the Laz Orthodox clergy and subsequent conversion to Islam or Hellenization of the Laz people. Local orthodox inhabitants, once subordinated to the Georgian Orthodox Church, had to adhere to the rules of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, resulting in the Hellenization of Laz people. Lazes who were under the control of Constantinople soon lost their language and self-identity as they became Greeks and learned Greek, especially the Pontic dialect of Greek, while the Laz language was preserved by Lazes who had become Muslim.

In a similar way, persecuted and oppressed Grecophone Greek Orthodox Christians, who converted to Islam, preserved their language and certain Christian traditions. However, religious and not linguistic or ethnic affiliations prove to be a decisive identity feature both in Turkey today and in Greece. Despite their ethnic Greek origin, the contemporary Grecophone Muslims of Turkey have been steadily assimilated into the Turkish-speaking (and in the northeast Laz-speaking) Muslim populations. This is also due to the close association of Greece and Greeks with Orthodox Christianity. In Greece, Greek-speaking Muslims are not generally considered as forming part of the Greek nation. Historically, Greek Orthodoxy has been associated with being Romios, i.e. Greek, and Islam with being Turkish, despite ethnic or linguistic references.

H.F.B. Lynch: Ottoman Muslims of Greek Orthodox Origin

The British traveler, businessman, and liberal Member of Parliament travelled Armenia on two occasions in the 1890s, including the Black Sea provincial capital of Trebizond. These are his comments on the Islamized Greeks in the east of the Trebizond province:

„(…) There are whole villages on this seaboard whose inhabitants are Mussulmans, and who resent being called any other name than Osmanli; yet their Greek origin is established both by history and by the traditions which they themselves still in part retain. Thus take Surmeneh [Grk.: Sourmena; Ottoman Trk.: Sürmena; today: Sürmene] and Of [Grk.: Ofis], two villages on the east of Trebizond. These versatile Greeks are as famous now for their theological eminence as they were formerly under the Eastern [Roman] Empire, with this difference, that whereas in those days they supplied the Church with bishops, it is now mollahs that they furnish to Islam. Yet, fanatical as they are, they still hold to certain customs which connect them with the old faith they once served with such distinction, and have, no doubt, since persecuted with equal zeal. Under the stress of illness the Madonna again makes her appearance, her image is again suspended above the sick-bed; the sufferer sips the forbidden wine from the old cup of the Communion, which still remains a treasured object with the whole community, much as they might be puzzled to tell you why. (…)”

Quoted from: Lynch, H.F.B.: Armenia: Travels and Studies, Vol. One: The Russian Provinces. Beirut: Khayats, Third Printing, 1990, p. 11f.

Cryphi, klosti, Stavriotes, Kromledes: The Crypto-Christians of Pontos

The crypto-Christians were Greeks who due to Muslim persecution publicly declared themselves Muslims. However, in secret, they upheld their Greek language, customs and Christian religious practices.

Crypto-Christians have been present in the east of Pontos since 1650, resulting from the fanaticism of certain Derebeys (valley lords). During this period, the Ottoman Empire was split into ‘Derebeylics’, or feuds. In many cases, the leaders in those areas showed exceedingly high fanaticism, and oppressed the Christian population, thus forcing them to convert to Islam. The Islamization of the Pontian Greek population first appeared in the Ofis region, followed by Sourmena [Sürmene], Argyroupolis [Gümüşhane], Ionia and other regions.[5]

Crypto-Christians are not polygamists, but practice endogamy. They were married in a Christian as well as a Muslim ceremony. The Christian marriage ceremony was often conducted in a rock-hewn house or one underground. When a Crypto-Christian died, a Christian funeral took place as well as the usual Muslim one. Up to the mid of the 19th century their Christian ceremonies were conducted with great care, but by the early 1900s as long as the men registered themselves as Muslims (thus available for military service), nobody asked whether they were Christian or Muslim at heart.

Crypto-Christians followed the Orthodox fasts. Their children were baptized, and bore both a Christian and Muslim name for secret and public use respectively. They never allowed their daughters to marry Muslims, but the men did take Muslim wives. In the latter case, the Christian marriage was conducted in secret, in one of the monasteries. If pressure was required, the bridegroom threatened to leave his bride.[6]

Konstantinos Emm. Fotiadis: The crypto-Christians of Pontos

In Pontos, thousands of Christians who “quit halfway along the road to our national Calvary, whose cross fell from their shoulder and who cheated their executioners”[7], found the strength to resist forced Islamization in an unique way that allowed them to avoid both death and conversion. They are the ones who were compelled to accept Islam after fierce battles with their conscience, though only ostensibly. They retained their Christianity in the depths of their soul and, whenever conditions permitted, the Greek language, too. In this way they managed to remain true both to their Orthodox faith and their linguistic identity. Pericles Triantafyllidis explains this phenomenon as follows: “Greek Christians who could neither consent to renounce the faith of their forefathers and their ethnic origins, nor endure continued persecutions at the hands of the despots managed to reconcile the two. Outwardly, they appeared to be Muslims and in secret, Christians, thus retaining both their religion and identity.”[8]

Keeping up their faith and the attempt to sustain it in future generations was to become the focal point of their lives and determined the conditions of their communal lives. The marriage contracts between young people exclusively from crypto-Christian families are illustrative, as is made clear by the following folk song, in which a Pontian mother reveals the secret of her Turkish groom’s Greek origins to her daughter:

Siona, don’t torture yourself or be of heavy heart/You’re to exchange a golden name for a Turkish one/ You’ll get a husband of solid gold, a Christian lad /Called Mahmut Ağa abroad and Nikolas at home / At the monastery at midnight you’ll exchange your vows.[8]

The ordeal of concealment, which continues to this day, was revealed for the first time in 1856. On publication of the Sultan’s Hatti Hümayun edict, which promised religious and political freedom to all subjects of the Sultan, the crypto-Christians of Pontos congregated in March 1857 at the monastery of Theoskepastos, where they vowed to fight to the final victory in defiance of exile, death and any other torments with which the Turkish authorities could coerce them.[9] Within a short while, this dynamic committee achieved the recognition and rehabilitation of these first crypto-Christians. Entire villages in the regions of Cromni, Matsouka (Maςka), Sourmena [Σούρμενα; Trk.: Sürmene], Santa, and Imera raised the flag of ethno-religious revolution one after the other, revealing the secret hidden for so many centuries. Thirty thousand crypto-Christians were registered as Christians by the committees formed in 1887, in collaboration with the local authorities and representatives of the Great Powers and the Christians of Pontos.

The first diplomatic victory of 1857 lifted morale and resulted in entire villages, which until then even the Greeks had thought were inhabited by Muslims, to boldly proclaim their faith. The British Consul in Trebizond, F. Stevens, participating in the same local investigation of 1857 to establish the number of crypto-Christians, recorded 9,533 Muslims, 17,200 crypto-Christians and 28,960 Christians in 55 villages in the region of Cromni, Argyroupolis [Gümüşhane], Santa and Hapsiköy.[10] On seeing the extent of the crypto-Christian population, the Ottoman authorities did not permit the operation to proceed as they feared the Christianization and Hellenization of the entire region. According to research done by the Center of Asia Minor Studies [Athens], in this region of the Pontos, there were 1,454 Greek-speaking villages.[11]

Quoted from: Fotiadis, Konstantinos Emm.: The Genocide of the Pontian Greeks. Monee, Ill., 2019, pp. 33-36

“The Young Turks movement, promising unity, justice, equality and freedom, held out some hope of a final solution to the crypto-Christian problem. These hopes soon died, however, when the hard-liners—whose political slogan was ‘Turkey for the Turks’—won control. The pressure applied by the Christian members of the Ottoman parliament, especially by M. Kofidis and G. Bousios, and the political circumstances of the parliamentary sessions of 1908-1910, forced the Young Turks to take a stand on this long-running political issue which was an affront to the democratic principles of the empire. In 1910, the Young Turk parliament was compelled to recognize as Orthodox Christians, or members of the Rum millet-i, a broad swath of crypto-Christians, but not all of them. Thus the problem remained unsolved until the mandatory exchange of populations and beyond it even to today.”

Excerpted from: Fotiadis, op. cit., p. 79

“Since this population exchange [1923] was based on religion alone, and did not take other characteristics of ethnicity into account, the Greek-speaking Muslims in the areas of Ofis (Of), Matsouka [Maςka] and Tonya, as well as the Greeks who continued to live as crypto-Christians, were exempt. In the period before 1923, the crypto-Christians had neither the means nor the opportunity to openly express their faith, due to the Turkish policy of pogroms, exile, and massacres towards the Greek population. The terms of the Lausanne Treaty presented them with an unexpected turn of events, and some of them managed to leave the country, either during the population exchange or a few years later. The Turkish government was tolerant, provided they remained in control of the process, and did not impede the exchange. Its main goal was to rid themselves of these troublesome ‘Muslims’.”

Excerpted from: Fotiadis, op. cit., p. 550

Theofanis Malkidis: The Crypto-Christians of Pontos

Crypto-Christians (or Klosti) have been present in Pontos (…) since 1650, resulting from the fanaticism of certain Derebeys (valley lords). During this period, the Ottoman Empire was divided into ‘Derebeylics’, in other words, feuds or themas. In many cases, the leaders in those areas showed exceedingly high fanaticism, and oppressed the Christian population, thus forcing them to convert to Islam. The early attempts towards the Islamization of the Pontos Greek population first appeared in the Ofis region, followed by Surmena [Sürmene], Argyroupolis [Gümüşhane], Ionia and other regions.

In public, these Christians exhibited the typical appearance of a Muslim and took part in the usual Islamic rituals just as a genuine Muslim would. At the same time, they could be found in places where undercover priests held liturgies and were present at all private gatherings associated with the Christian Orthodox faith.

The Crypto-Christians avoided arranged marriages to Muslims in many ways, thus allowing marriage between Christians to continue. This lasted until February of 1856, when pressure by the European powers on the Sultan led the way to the signing of the Hatt-ı Hümayum which resulted in all Ottoman citizen being allowed the right to revert back to his or her original creed, in this case Christianity. This policy existed between 1856 and 1910, however the policy changed in 1910 with the arrival of the Young Turks and their implementation of a Pan-Islamic policy. Until then, it was not unusual to see entire villages in Pontos revert to Christianity

The Reform (Tanzimat) Period

The period of great change in the Ottoman State, the ‘Tanzimat’ era, was initiated by the Sultan Abdül Mecit (1839-1861) and his Act, the Hatt-ı Şerif [Imperial Decree] in the year 1839, which was ratified and later expanded to the Hatt-ı Hümayun in 1856. (…) The consequence of these reforms affected the economy, with an increase in trade with Europe, a more intense penetration of Western business firms, and a re-organization of local agricultural produce with a hope for the Empire’s survival, as well as political, economic and social effects particularly with regard to the non-Muslim population. Thus the most serious repercussions of the reforms was the future of social development. Greek-Turkish relations were therefore directly connected with the existence of Crypto-Christians within the Ottoman Empire.

(…)

This new act however was not widely accepted because the Muslim population reacted against the better welfare of the Christians (…).

The Hatt-ı Hümayun of 6/18 February 1856 was issued after pressure exerted by the European powers whose aim was the establishment of equal rights to the Christians of the Ottoman Empire. In this way they were also depriving the Russians of mixing with the affairs of the Ottoman state. By enforcing the Hatt-ı Hümayun, all Christians obtained equal rights with Muslims in terms of religion and legality. To this the Sultan emphatically said: “My heart makes no exception between the slave of my empire. Rights and privileges will equally be shared with no distinction to all with no exception”. In towns and villages Greek-Christian schools were opened. Freedom to worship one’s own religion was granted both inside and outside of the church which was one of the most important changes. The Ottoman state ratified the National and General Regulations of the Patriarchy, which would become the Constitution chart of the Orthodox Church till 1923.

(…)

From 1856 until the official recognition of Cappadocian and Pontic Crypto-Christians by the authorities in 1911, there were several sources detailing the Crypto-Christians with the most characteristic being that of P.S. Sideropoulos (or Pehlil), who unveiled himself to his boss the Italian Consul Fabri. On May 14th, 1856, Sideropoulos was finally recognized as a Christian by the Ottoman authorities. This was great news for all those who were still hiding their true faith, and on July 15th, 1857, 1590 Crypto-Christians congregated at the church of Theoskepastos in Trebizond, after a memorandum to the Sublime Porte, the ambassadors of the European Powers and the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

A report of the British sub-consul A. Stevens in 1857 addressed to the British ambassador Stanford regarding the Kromni district in Pontos, stated that in 55 villages, 9,535 Muslims resided there, 17,260 Crypto-Christians and 28,960 Christian Greeks. Gervassios, the Bishop of Sevastia [Sivas] made reference to the Crypto-Christians of Asia Minor by saying that, after European interventions there in the year 1858, 25,000 of them confessed publicly their Christian creed. The return to Christianity by these Ottoman subjects frightened the authorities who followed the developments with great unease.

To hinder these changes, the names of Christians on official lists were altered with the addition of the words ‘Tenesur Rum’ beside their names. This basically meant that he or she was an apostate or a denier of his or her creed. Christians who were labelled in this way had to undergo the corresponding added sufferings. Their children were not allowed to inherit their parents’ properties. The proceedings were implemented with the aim of halting the trend of Christians returning to their former creed but also to safeguard domestic income.

The period after 1869 is characterized by an increase of persecutions towards the crypto-Christians. Some tried to gain Russian citizenship in order to escape further discrimination. In the year 1876 there were acts of violence in the Pontos region which persisted for many more years.

The reforms that took place in the Ottoman state came to a peak in 1876 together with the preparation of the New Constitution by the Grand Vizier Midhat Pasha, the head of the Young Turkish movement. During this period, the Ottoman state took the shape of a Constitutional monarchy, but soon Sultan Abdül Hamit II abolished the Parliament. It was only shortly before the Young Turkish movement in 1908 that he was forced to proclaim the second constitution for a new parliament assembly on 23 July 1908.

The 1876 Ottoman Constitution and the Crypto-Christians

The constitution resulted in the equality of rights among all citizens to be declared for all religions and it was then that crypto-Christians of Cappadocia openly declared their creed. The Greek Stavriotes, who took their origin from the Stavroti village, led a double life for a great length of time, being Christian in private and Muslim in public. During the Easter of 1877, 300 Stavriote families were bold enough to publicly declare their Christian creed celebrating “Resurrection”, in church thus taking advantage of the constitution. The 1876 constitution charter was no longer in use and formally, nothing changed in their district. People were able to send their children to Greek Orthodox schools, attend church and go to matrimonial ceremonies. Up until 1898 the Ottoman authorities took a soft approach towards these events, but after the 1897 Greco-Turkish War, wild persecutions broke out against Asia Minor Christians, especially in the neighbouring Trebizond area. The Abdül Hamit’s ‘Kulturkampf’ (cultural battle), waving the Pan-Islamic flag, resulted in bloodshed. The Sultan put forth a plan towards an enforcement of Ottoman culture fomenting religious devotion to Islam. Studying in Greek schools was banned, children born by non-recognized Christian parents were considered ‘bastards’ and illegitimate, and on a grand scale military enlistment was carried out.

The Young Turks and the Crypto-Christian Question

(…) In the first phase of the Young Turkish movement there were groups with differing objectives to that of the leading group, and the atmosphere in general was expressed by slogans and the general policy of a Pan-Islamic Ottomanism, Turkish nationalism and modernization. Very few of these groups thought that Christians and Muslims should have equal rights within a modern Muslim state. Some followers of a Pan-Islamic ideal advocated for the forcible Islamization of the Christian population and particularly the children, a movement which was met with the approval of those living in the remotest parts of the Empire, and away from urban districts where Christians were a minority.

The Islamization issue developed into a serious one for the Patriarchy and the church in general, forcing its religious leadership to send out ecclesiastical reports (takriria) to the Ottoman State with the aim of discussing the particular problems.

The Young Turks appeared in the decade of 1870 with the so-called Modern Ottoman party, a party of liberals who owned big farm properties, and the small bourgeois class, which had just started to come into being. With the bankruptcy of the Ottoman State in 1875, the party, mobilizing the people, made Sultan Abdül Hamit II appoint the Great Vizier Midhat Pasha, who despite wearing the mask of political liberalism and of rights, amalgamated the non-Muslim citizens with Islamic and Turkish ideology. The Young Turks took shape with the establishment of their own club, Unity and Progress at the Military Medical Academy of Constantinople in 1889. But the climate of freedom did not last long, and the leaders of the movement were persecuted and gathered close together around the exiled ‘Committee’ of Union and Progress in Paris (1897). (…) As a result of the 1905 census, and (…) the 1908 revolt, matters again led to tension concerning the crypto-Christians and Stavriotes who were demanding to be registered as Christians, a request which was answered with acts of violence.

The 1908 Young Turkish revolution resulted in the Sultan restoring the parliament which he suspended 1878. This was welcomed by Christian Greeks and other minorities and religions. But they soon realized the chauvinistic character of the Young Turkish movement, which was now planning the extermination of the non-Muslim inhabitants. It was a period characterized by a seeming retreat of the Ottoman administration on the relevant demands of crypto-Christian recognition. Through memoranda, Stavriotes attempted to bring their demands into action once again, but it took them at least 2 or 3 years before a tentative solution was given with the acceptance by the Young Turks of the Crypto Christian problem. (…) Although the Young Turks spoke for reforms, they were practically chauvinists. Turkish was established as the official language. Up to secondary school, the language used was now solely Turkish. The right to become a Member of Parliament was only allowed to those who had good knowledge of the official language and their ‘Ottomanism’ was proclaimed as their national ideal. It was a way of practically denying the existence of other nationalities, and the attempt to assimilate them by force. (…)

At the Young Turkish conference in Thessaloniki in 1911 decisions were adopted which turned against every non-Muslim minority who lived within the boundaries of the Ottoman State. “Turkey should eventually become a Muslim country. The Mohammedan’s concept and power should keep control throughout the country. Any other religious propaganda should be banned. The existence of the Empire depends on the forces and power of the Young Turkish party and the crushing of any other ideology antagonizing it. The Muslimization of peoples should be completed as soon as possible. Of course, it is clear that it cannot be accomplished by convincing them and that the only way is to use armed force. The feature of the empire should remain Mohammedan and upon this we should see that Muslim laws and decrees will be respected by all. The right of all other nationalities to have their own organizations should be obliterated. Any form of decentralization or self-administration will be considered treason for the Ottoman Empire. Nationalities are elements of no value. They may be allowed to keep their creed but not their language. Expanding the Turkish language is one of the most basic principles for securing the Mohammedan superiority and the assimilation of non-Mohammedan populations”.[13]

(…)

The present status of Crypto-Christians of the Pontos dialect speakers

(…) Nowadays, there are almost no crypto-Christians living in Turkey. (…)

Regarding the numerical data of Greek speaking Crypto Christians, only assumptions can be made. In Sourmena, the capital of the district consists of 19 villages, 5 of which today are populated purely by Greek speakers. The Sourmena Pontians, who have a special tendency to education, business and fishing have numerous settlements in Constantinople. In the Galiena district (ancient Guliena) which consists of 18 villages and settlements, half the population of the district are Islamized locals while the other half have re-established themselves from the villages Kullish and Archangelos of the Sourmena district in the 3rd decade of the twentieth century. The Turkish language has only recently started to replace the Pontic dialect, which is not spoken by young people, at least below the age of 20.

The Tsa΄kara region (Kato-Chorion) is purely Greek-speaking and the last to become Islamized (end of 19th century) with a sufficiently highly developed religious feeling of Crypto-Christianity. Recently its youth have been affected by leftist ideas and a claim of self-determination, self-recognition and a search for their own identity. The inhabitants are mostly stock breeders while many have migrated to Istanbul where they have constituted a powerful federation, working as scientists, businessmen and statesmen, e.g. from the ‘Sineck’ village of Katochorion the former president of Turkey, Cevdet Sunay (1899-1982; presidency 1966-1973) drew his origin.

The Of district (ancient Ofis region) consists of 49 villages which were completely Greek, but nowadays only Evenköy remains as a Greek-speaking village. There the Muslim celebration of Ramadan takes place, and Triod which comes from the Greek Triodion. The majority of its inhabitants are Muslims (…). The inhabitants, mainly yeomen and stock breeders, have re-established their communities in Constantinople and other cities. The Greek-speaking writer Ömer Şükrü Asan from Erenköy [Çoruk; born 1961], who has published the book Pontos Culture (Pontos Kültürü; 1996) in Turkish, has greatly contributed to the search for identity of these people. (…)

Ano Matsouka (Upper Matsouka) consists of 8 villages located at the Zygana pass with Hapsiköy at the very center. It contains Christian Greek villages of which the greatest majority of its population derive from Greek speaking settlements from the Tonya district that settled there after 1924. Greek speaking communities of Ano Matsouka can be found today at Yalova, Geyve and Istanbul itself. The Tonya district (ancient Thoania) consists of 18 villages, 7 of which are purely Greek speaking. The people of the surrounding area still preserve elements of their Pontic Hellenism, while at the same time they are renowned for their love of weapons and preserving the custom of the ‘vendetta’. It is from the Alexandrana village that the former minister A. Sener originated. (…)

In conclusion, given the lack of numerical data, and the Turkish authority’s fear of conducting research into its national origins and minorities, it is far too difficult to do a thorough evaluation in regards to the number of Pontos Crypto-Christians which exist in Turkey today.

Socially, the Pontos crypto-Christian Greek speakers, were, and still remain, a conservative unit group of people, with tight bonds between each other, their family and their relatives. As mentioned, they continue practicing endogamy, and they are extremely resistant to any changes imposed on them. For instance, changes that are imposed by the Turkish authorities aimed at the introduction of a unique Turkish identity and language.

Nevertheless, during the last few decades and years, a feeling of a specific identity is increasing amongst them. Any attempt from the youth of Pontos to express in words or text their Pontian dialect, history or cultural identity is faced with hatred by the Turkish authorities, whilst the lives of Pontians who dare to express their views are threatened. This oppression is accompanied by pseudo-scientific attempts at distorting the rich history of these people and their region, as the official Turkish policy is that their historic identity is of Turkish origin.

Concerning the language, it seems that a large part of the Islamized Greek speakers of Pontos, particularly in the Trebizond (Trabzon) district, in Tonya, Ofis, Sourmena, Matsouka as well as some in the Istanbul boroughs, have preserved their Pontic dialect virtually unchanged. So in those districts, the language, which is illegal in Pontos and all other parts of Turkey, helps them to bond and to keep their identity. Of course, there is not a single school in Turkey where Pontians are able to learn or promote their language. Pontos youths, especially those coming from inland, due to their families keeping their own language and not knowing Turkish, first come in contact with the Turkish language at school and have to learn it through rigorous teaching methods. Even in Primary schools there is a net of young pupils who reliably inform and pass on information to their teachers. Pontian schoolmates who speak the Pontos dialect in private may be subjected to strict ‘convincing’ methods by teachers or even the police. At Junior and Senior High Schools the work of ‘terrorizing’ is handed over to racists and clans of fascists like for instance the Grey Wolves. Under these conditions Pontian students are excluded from Universities and Colleges. Students of Pontic descent who make an attempt to show their Pontic origin and culture by means of printed material are forcibly discriminated against. One instance being when a Pontic magazine was issued at the Trabzon University in 1999. The students responsible faced the danger of being sentenced to imprisonment by the Turkish authorities. According to Turkish policy, any activity by youths which may concern their Pontic identity, is an attempt to re-establish the ‘Pontos Empire’.

(…)

On an official level, the Greek state does not involve itself with the question of the Greek speakers (crypto-Christians) of Turkey. Only the Greek society shows some level of interest, either through Pontian societies or non-government organizations. The Pontian associations, through presentations to Greek, Turkish and other official groups, have tried to raise awareness of the Greek speakers of Turkey and the oppression they are forced to endure. The restrictions in Turkey today on the lack of freedoms of Islamized Pontians has been denounced by the non-governmental organization The International Union for the Rights and Liberation of Peoples with a written memorandum to the Organization for the European Security and Co-operation (O.S.C.E.) and also the Human Rights Bureau of the U.N.O. In Switzerland there was also a verbal intervention at the 58th meeting of the U.N.O. The same subject was addressed to the Committee for the Human Rights and by the French non-government organization ‘AMRAP’ (The Movement Against Racism for Friendship Among Peoples). (…)

Conclusions

(…) the problem of crypto-Christianity is still affecting the whole of Asia Minor (Turkey) and Pontos today. Persecution is the dominant feature. After the outbreak of World War I, persecutions against Christians became more intense by the Young Turks’ regime, of which the Stavriotes, the inhabitants of Mt Ak Dağ, were the most severely tortured. Through Islamization, they tried to avoid the tortures. (…)

In Pontos, after the Russian army had retreated in 1916, those who had recently declared their Christian creed were tortured whilst their enlistment to the Labor Battalions was intensified. The First World War was followed by the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) which resulted in a re-escalation of tension and persecutions. After the Lausanne Treaty, and an earlier agreement concerning an exchange of populations (only for those who had officially turned to Christianity), it left many crypto-Christians behind. Nowadays the problem of Greek speaking crypto-Christians is part of a saga which has lately filtered into talks between Greece, Turkey, Europe, U.S.A. and other world organizations.

Excerpted from: https://pontosworld.com/index.php/history/articles/242-the-crypto-christians-of-pontus?showall=1