Together with the kaza Mahmudiye, the kaza Elbağ was one of the first Ottoman administrative units inhabited by Christians to host massacres in November and December 1914. The Dashnak representative and Armenian MP for the province of Van, Arshak Vramian (1871-1915), protested in vain in March 1915 in a memorandum to Ottoman Interior Minister Mehmet Talat:

“In March [1915], Vramian sent a memorandum to the minister of the interior about the massacres that had occurred in the kazas of Başkale and Mahmudiye and, more generally, the insecurity reigning in the region.”

The preparations that the Itthatist Ömer Naci was making with a view to forming squadrons of çetes did not, of course, go unnoticed by the Dashnak leaders.

“Vramian began with the observation that 150 hamidiyes of the Kurdish Mazrik tribe, led by Sarıf Bey, took part in the attack in the Armenian villages of Başkale. Turkish military sources, he went on, pointed to the Armenian resistance to the successful Turkish attempts to recapture the little town to justify this intervention, while simultaneously criticizing the Armenians for ostensibly following the retreating Russian troops. Vramian pointed up this contradiction, asking whether it was conceivable that the Armenians had abandoned their families and fled with the Russians. He added that ‘the local authorities in Başkale report[ed] only that they ordered the arrests of eleven men whose names are cited in their report. These men were ordered to go to Van and murdered on the way. This was why I made a number of personal appeals to Mehmed Şefik Bey, the interim vali, requesting that he authorize a local inquiry with a view to compiling a list of the killed and missing and providing their poverty-stricken families with aid.’

Vramian remarked that his appeals had fallen on deaf ears, as had his proposal to transfer to Van a few ‘of those unfortunates, who could have given us information about the situation’.”[1]

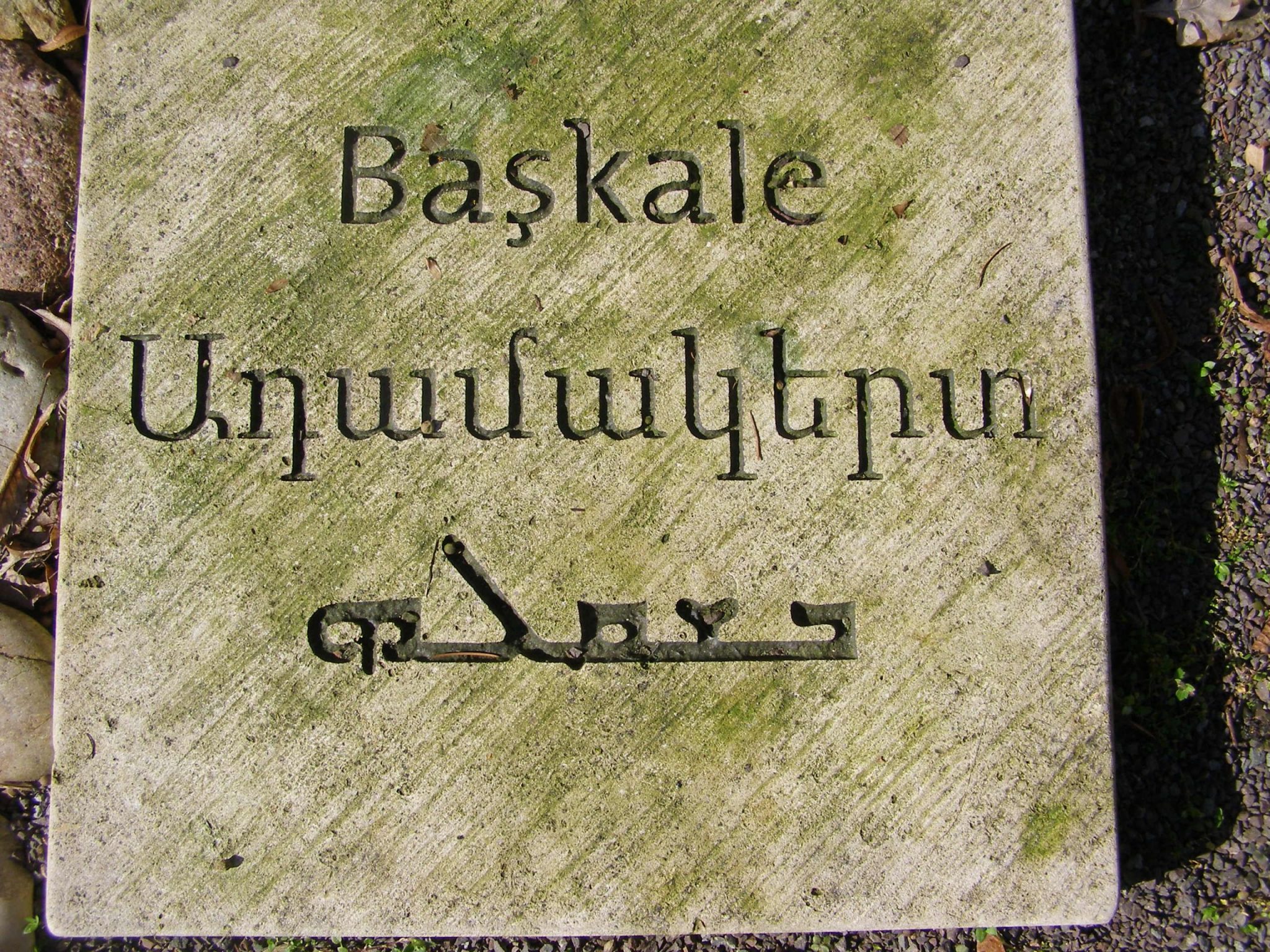

Başkale / Aghbak / Elbağ / Adamakert / Hadamakert – Ադամակերտ / Հադամակերտ

Başkale is situated 2,460 meters above sea level, in the Valley of the Great or Upper Zab River (Büyükzap Suyu), standing on the eastern slope of the southeastern Taurus Mountains.

Toponym

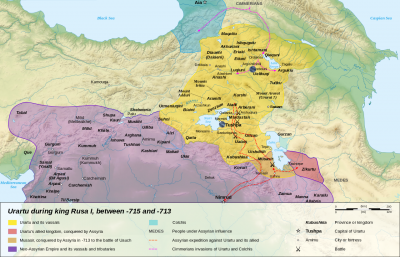

The history of Başkale goes back to the Urartian town of Adamma in the first pre-Christian millennium. The Urartian place name lives on in the Armenian designation Adamakert, which is documented since the second century B.C., whereby a popular etymology in Christian time derived it from ‘Adam’s fortress’.

History

Adamakert or Hadamakert formed the main fortress of the district Aghbak Medz (Աղբակ Մեծ) of the western Armenian province Vaspurakan. Only 20 km away from today’s Turkish-Iranian state border, the border location between rivalling empires shaped the fate of the people living here over long periods of history. Since the year 385, the fortress Adamakert and the region Aghbak Medz were contested between the Parthian Empire and Eastern Rome (Byzantium). This situation repeated itself in the first half of the 16th century during the supremacy battles between the Ottoman Empire and Safavid Iran. In the late 19th century, H.F.B. Lynch learnt that 25 Jewish families resided in Başkale.[2]

On 30 October 1914, approximately 50 Assyrians (East Syriacs) from the Gavar plain in the homonymous kaza were murdered in the local government center of Başkale

Monastery of St Bartholomew (Սուրբ Բարթողոմէօս Վանք)

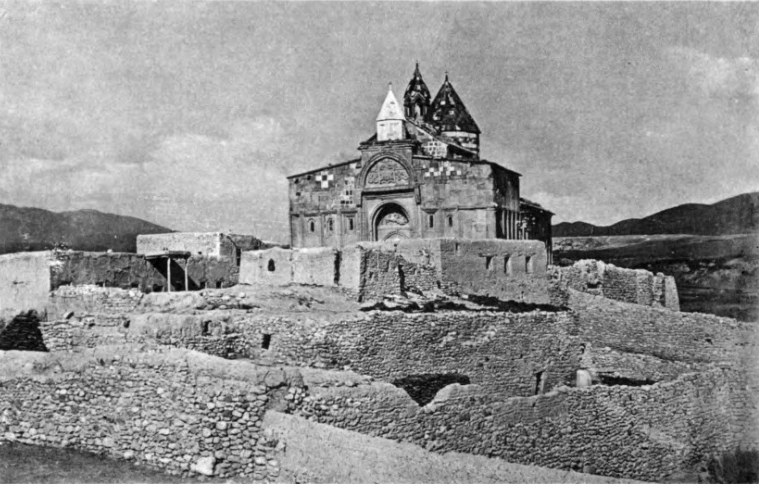

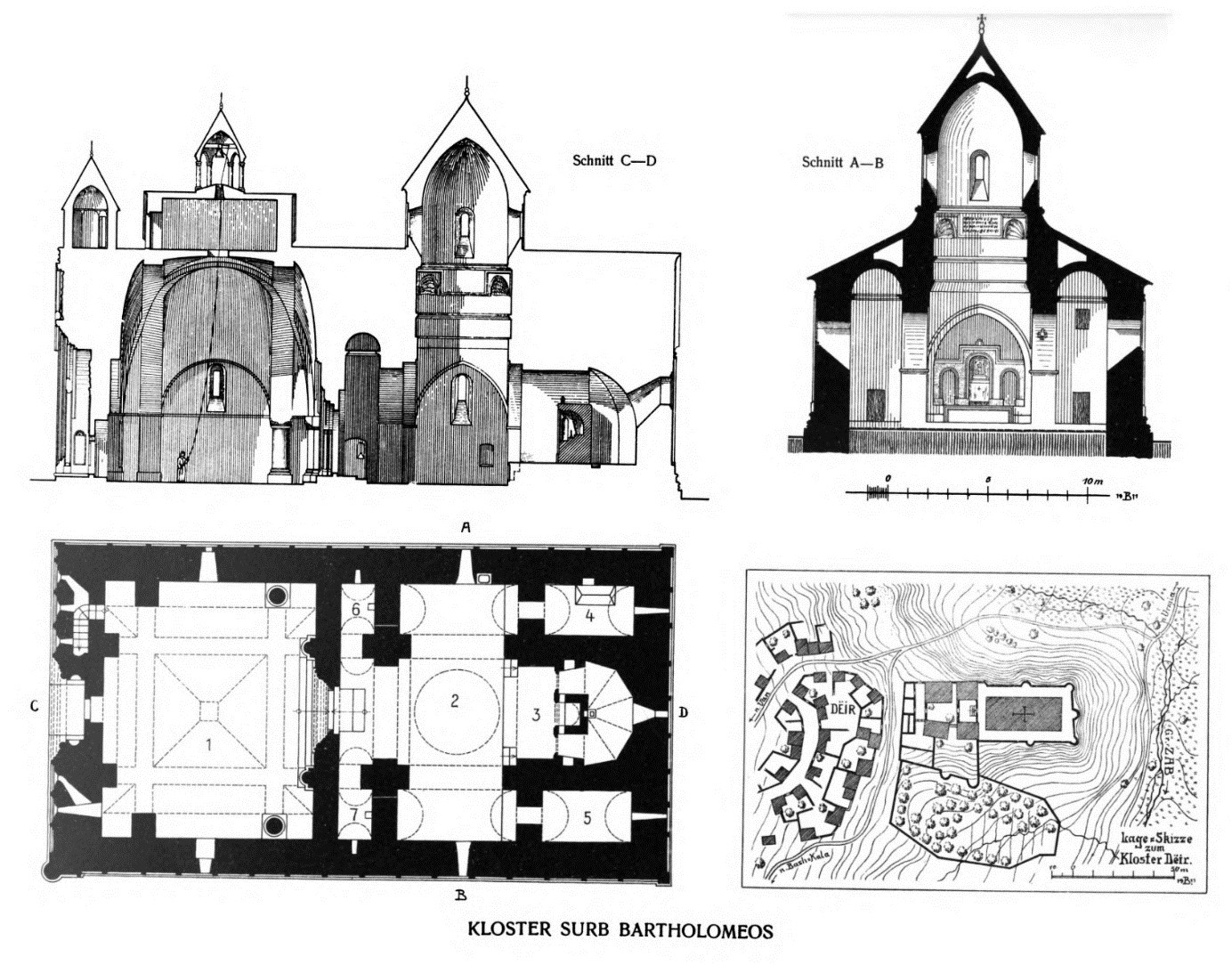

Near to the Iranian border and 23 km northeast of the town of Başkale lies the Monastery of St. Bartholomew on a hill about 2000 meters above sea level; it offers a direct view into the Valley of the Great Zab River (Büyükzap Suyu).

According to Armenian Church tradition, the Christianization of Armenia goes back to the missionary activities of the apostles Jude (Judas Thaddeus) and Bartholomew, who suffered martyrdom in Armenia around 66 and 68 A.D. respectively; both are venerated as the patron saints of Armenia. Memorial churches were early built on the sites of these Apostles’ martyrdom, which were expanded into important monasteries in the middle Ages.

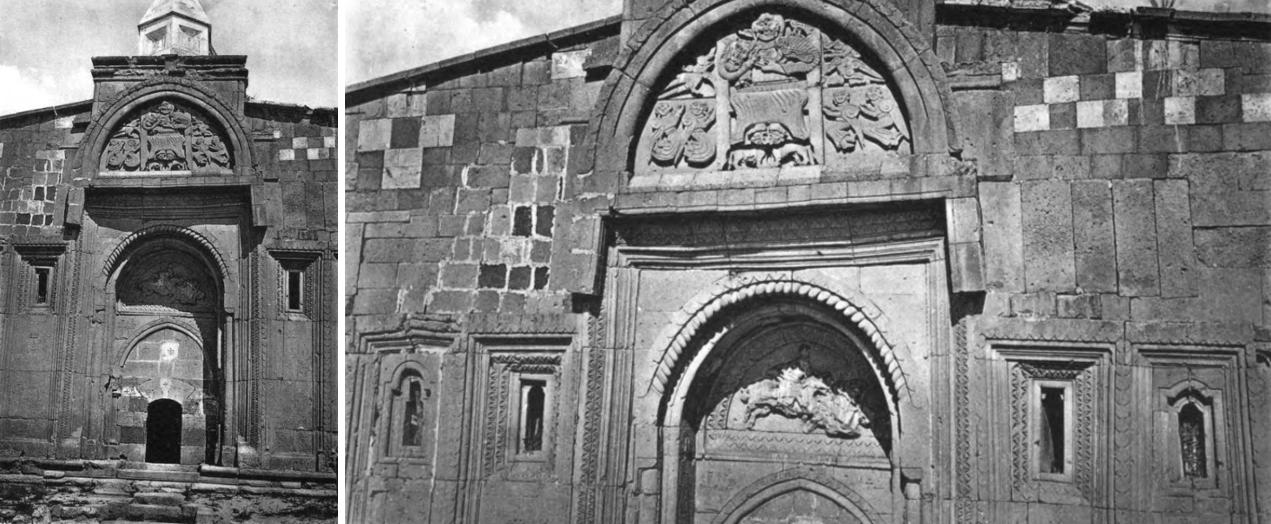

According to tradition, St. Bartholomew Monastery was founded in the first century after Christ by the Armenian king Sanatruk Arshakian over the tomb of the apostle Bartholomew, who had healed the king from leprosy. The tomb bore the inscription: “This is the ark of the remains of the Holy Apostle St. Bartholomew, the first Enlightener of Armenia” («Այս է տապան հանգստեան սբ. Բարդուղիմէոսի սրբազան առաքելոյ առաջին լուսաւորչին Հայաստանեաց աշխարհի»). The apostle’s tomb was located in the sacristy in the northern part of the later main church of the monastery, which probably replaced an older basilica in the 13th century. To the west of the main church (katoghike) stood a gavit (narthex), which was stylistically similar and lightened by a skylight dome in the center. Further west of the gavit stood the bell tower. The western façade of the gavit had a large portal with the sculpture of, what was believed to be, Bartholomew the Apostle on a horseback, killing a dragon. At the top of the portal, there was a semi-circular sculpture of the Holy Trinity. The portal and the sculptures are considered one of the finest in Armenia.

In the 14th century, at the end of which the monastery was first mentioned in writing, it became more widely known. It had a scriptorium where a gospel was written in 1339 and Vardan Areveltsi wrote his Historical Compilation (1398).

In 1647, the monastery of St. Bartholomew formed a single congregation with the nearby monastery of Varagavank. In the late 19th century, the Monastery of St. Bartholomew was the seat of the diocese, which covered region of Aghbak, Julamerk, Salmast, and Urmia. It included around 100 Armenian villages and large territories of pastures, fields, and forests. It was a prominent pilgrimage site.

Frequent earthquakes did repetitive damage to the two churches of the monastery, in particular the dome. Father Kirakos repaired the monastery in 1651. A 1715 earthquake destroyed the dome, which was rebuilt by Hovhannes Mokatsi of Lim in 1755–60, but ruined again in 1860 (rebuilt in 1878). The monastery prospered in the second half of the 19th century. A school was opened at the monastery.

During the genocide in 1915, the monastery was abandoned and came under the control of Ottoman armed forces; it has since been part of a Turkish army base; access is prohibited. In 1966, an earthquake severely damaged the surviving buildings, which are now standing as severely damaged ruins without a dome. However, Armenian scientists doubt that the destruction of the Bartholomew Monastery can only be traced back to earthquakes. They refer to the systematic destruction by the Turkish military to which Armenian monuments were subjected, especially in the 1960s.

Lack of Monument Protection in the Republic of Turkey

“According to UNESCO’s data for 1974, 464 out of the 913 Armenian buildings that remained standing after 1915 were totally annihilated, 252 were reduced to ruins, while 197 are in bad need of immediate reconstruction. Contrary to the fact that Turkey passed a law on the preservation and reconstruction of historical monuments, up till the present no Armenian monument has been repaired in that country without the alteration of its Armenian characteristics. At present the ‘restoration‘ of the walls of Ani is underway, but its initiators are actually implementing a program of changing their Armenian features.

The Armenian architectural monuments that are being persistently blasted become targets during the military exercises of the Turkish army, whereas their finely-finished stones are used as building material. The standing ones serve as cattle-sheds, warehouses and even jails: sometimes they turn into mosques, or are declared monuments of ‘Seljuk architecture’.

The Turkish Government often substantiates the destruction of the Armenian churches with earthquakes taking place in this zone, but how do the same earthquakes fail to damage the monuments of Seljuk architecture?

Throughout many years, the Turkish mass media have disseminated rumours according to which on ‘leaving’ Turkey, the rich Armenians hid their jewelry under the stones bearing ‘gyavur’ (infidel) writings, or cross reliefs. Motivated by this disinformation, the present-day inhabitants of these territories destroy everything suggesting something Armenian in an insatiable desire to find those treasures.”

Source: Foundation Research on Armenian Architecture (RAA): The conditions of the Armenian historical monuments in Turkey. http://www.raa.am/Jard/FR_set_E_Cond_Turkey.htm (archived February 2019)

In July 2011, Van Governor Munir Karaloğlu visited the site and gave instructions to launch restoration works. As of 2014, no steps were taken to restore the monastery or prevent it from collapsing. In 2014 Anadolu Agency and Agos mentioned the monastery as a candidate of being restored in the upcoming years. Van Province Culture Director Muzaffer Aktuğ stated in February 2014 that the restoration works would start within that year and noted that it would boost tourism.