The kaza spread in the eastern part of the province of Sivas (Sebastia), in the valley of the river Tevrik (Trk.: Çaltı Suyu, a right tributary of the Karasu, or western Euphrates). The region has fertile lands, plenty of irrigation water and iron mines. Surrounded by orchards, the kaza‘s administrative seat was also called ‘green Divrik’.

Toponym

In ancient Greek texts the area is called Apbrike. After the partition of the Roman Empire in 395, it belonged to the Byzantine Empire. The name Apbrike was later adopted for the fortress Tephrike (Armenian: Tevrik, Divrig), strategically located above the narrowest part of the river, which is mentioned since the Middle Byzantine period (from the mid-7th century). Since 1252 the city and the region were known as Divriği.

Administration

At the beginning of the 20th century, the kaza was subdivided into 6 nahiyes with a total of 129 villages.

Population

By the 19th century, the city of Divriği had grown. The inhabitants profited from trade, especially in copper ore, which was mined at Ergani Maden (near Diyarbekir) and Keban and transported westward through the valley.

Armenian population figures differ by a factor of 2. According to some Armenian sources, in the early 20th century the kaza of Divriği had an overall population of 46,090 inhabitants; of these, 20,000 were Armenians.[1] Based on the census of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, Raymond Kévorkian puts the total number of Armenians in the Divriği kaza at 10,605. They lived in 18 localities, maintaining 18 churches, two monasteries, and ten schools with 857 students.[2]

„The administrative seat of the kaza, Divrig/Divriği, had a population of 12,000, almost eine third of whom were Armenians. Among the countless vestiges of the medieval period sprinkled through the region was the monastery of St. Gregor the Illuminator [Surb Grigor Lusavorich], a jewel of Armenian architecture built in the eleventh century that was perched on a rocky outcrop three hours north of Divrig near the village of Khurnavil (pop. 320). The neighboring village of Kemseh (pop. 580) and the native village of the Noradunghians [Նորատունկեան – Noratunkian] also boasted medieval churches, as did Zimara/Zmmar (pop. 1,250). Binga/Pingian (pop. 1,300), on the right banks of the Euphrates, was a medieval citadel that was nearly inaccessible because it was pressed up against a rock face close to the Euphrates. Its only access route ran over a suspended bridge that had been built in the eleventh century. In the southwestern part of the kaza was a string of Armenian villages on the two banks of the Lik Su: Arshushan (pop. 310), Kuresin (pop. 240), Odur (pop. 215) [Kayaburun], Parzam (pop. 510) [Parğam], and the village around the monastery of St. James that the Turks called Venk (from the Armenian word vank, monastery) (pop. 290).”[3]

Finally, at the eastern end of the kaza, on the right bank of the Çaldaçay, there were five other Armenian villages: Armutağ/Armutak (Kavaklısu), with 1,605 Armenians and the Church of Saint Kevork (Gevorg); Palanga (Ölçekli), with 480 Armenians and the Church of Saint Kevork (Gevorg); Sincan/Sancan, with 395 Armenians and the Church of Saint Kevork (Gevorg); Mrvana (Mırvana, Kayacık), with the Church of Virgin Mary, and Shigim.

Agriculture was widespread in the Divriği kaza. The inhabitants cultivated grain, grapes, various kinds of fruits, were engaged in cattle-breeding. Armenians were engaged in trade and crafts. The wine of Divriği was famous.

History

Tevrik was a district in historical Lesser Armenia (Armenia Minor).

At the end of the 6th century, Sassanids advanced into Anatolia several times, Melitene (today Malatya) and Tephrike suffered the same frequent changes of power. In 575 or 576, the Byzantines inflicted a heavy defeat on the Sassanids at the Battle of Melitene. Arabs invaded Anatolia in the wake of Islamic expansion around 650.

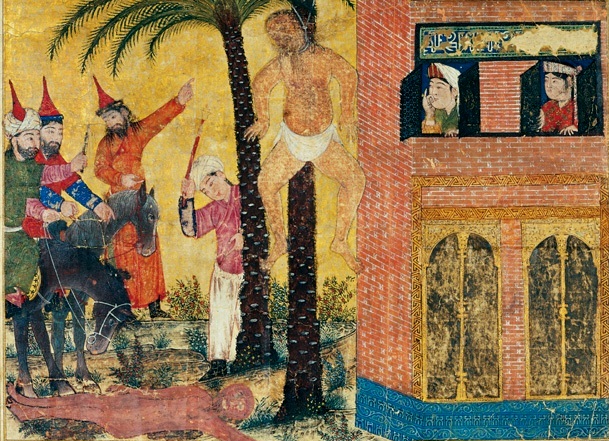

Around 843, the Byzantine village of Tephrike became the refuge and center of the Armenian sect of the Paulicians, who founded the first city here with the support of the Abbasid rulers of Melitene. The heretical sect members of the Paulicians were particularly persecuted by the Byzantine empress mother Theodora II (r. 842-867), before their leader Karbeas turned to the Emir of Melitene, who assigned them Tephrike for settlement. There, under the protection of the Caliph of Baghdad, they developed into a regional center of power in Central Anatolia, expanding the fortress and undertaking campaigns against the Byzantines. In 872, Emperor Basileios I Mamikonian (r. 867-886) defeated their leader John Chrysocheir in a battle and conquered the city. The Paulicians, who had become leaderless and weakened, moved in majority to Thrace, where they exerted influence on the later sect of the Bogumils. The city of the Paulicians may not have encompassed much more than the area of the citadel.

Until 1071 Tephrike belonged to the Byzantine Empire. During this period, a Byzantine military leader sat here, first with the title kleisourarch, later he was called strategos. The Divriği Valley may not have been particularly prosperous at that time. In 1071, the Seljuks under the leadership of Alp Arslan defeated the army of the Byzantine emperor Romanos IV in the Battle of Manzikert. After the battle (around 1100), Tephrike came under the power of the Turkish chieftain Mengücek, a vassal of the Seljuks, who established a principality (Beylik) in eastern Anatolia that existed until 1252. In 1252 the Mongols under Hülegü besieged the city and after their conquest destroyed the fortress and city walls as they had everywhere. A few years later Divriği was rebuilt.

Under Sultan Selim I, the city became part of the Ottoman Empire in 1516. On a hill on the opposite side of the river, a regional ruler (derebey) had the Kesdoğan Kalesi fortress built in the late 17th or 18th century.

Armenian “Heretics” and “Heresies”: The Paulicians

The Armenian Church found its dogmatic-theological identity not only in the overall Christian controversy, but just as intensively in the defense against heresies. Although the Armenian ‘heresies’ contain very diverse elements, the schools of Markion of Sinope, which was influenced by Gnosticism, as well as those of Mani became decisive.

Markion was born at the beginning of the 2nd century in the Pontic port city of Sinope, the son of a shipowner. He constructed his doctrine of an evil creator god, whom he held responsible for the world in its imperfection and equated with the Jewish creator god of the Old Testament. From this derived for Markion and the counter-church he founded the rejection of the entire Old Testament as well as the Ten Commandments, but also large parts of the New Testament were rejected. The imperfect Creator God of the imperfect world was contrasted with Christ as the messenger of a supreme and good, but alien God.

The second main source of Armenian heresies was the teaching of Mani (216-276), a Babylonian-born Parthian of the Arshakid dynasty. He too, strongly influenced by Iranian thought, starts from a dualistic worldview: the struggle of God or good against the realm of darkness and materiality. Through strict asceticism, however, people can be purified and support the fight against darkness.

The Paulicians, an anti-hierarchical sect that arose in Armenia at the end of the 7th century and had numerous followers until the late 9th century, are to be regarded as the direct heirs of the Markionites. Like its successor sects, it owed its popularity, among other things, to the social discontent of the peasant population and later also of the simple townspeople. The Paulicians called themselves simply Christians, but in reality, they were a Christian variety of Manichaeism. In Armenian sources, the name Paulician is attributed to the founder of the sect, although there are different accounts of his identity. Once Paulos of Samosata, a heretic Syrian theologian, is mentioned, another time a preacher of the same name, but from a later time. The designation apparently also alludes to the importance that the letters of the Apostle Paul, along with the Gospel of Luke, possessed for the Paulicians. This reduction of the New Testament to Paul’s teachings, along with the rejection of the Old Testament, had been adopted by the sect from the Markionites. Other Paulician features included the rejection of marriage, the sacraments, the priesthood, and the veneration of icons, including the cross. They also rejected the doctrine of eternal life and the Last Judgment.

While the Paulicians in Armenia suffered oppression as early as the mid-6th century during the reign of Catholicos Nerses II (548-557) and then bloody persecution around 695, they were initially tolerated by the Byzantine emperors – especially of the iconoclastic school. But already Emperors Michael I (811-813) and Theophilos (829-842) mobilized against the Paulicians, especially since the revolutionary explosive power of their movement was meanwhile generally perceived as a threat to the ruling order. With the final victory of the Iconoclasts in 843, the struggle against the Paulicians intensified. Just one year later, 100,000 of them are said to have been executed. It did little good for the Paulicians to raise their own troops and ally themselves with the Muslim emir of Melitene, for the imperial armies broke through the line of Arab strongholds and even destroyed the Paulician base of heretics at least as troublesome as the Byzantine rulers, the Paulicians were forcibly resettled for the most part to Thrace on the border of the Byzantine Empire around 875. Their missionary activity there among the Balkan Slavs gave rise in the mid-10th century, especially in Bosnia, to the successor sect of the Bogomils (after the priest Bogomil or Theophilos), which lasted until the Ottomans conquered the Balkans in the 14th century. In the 13th century, the Bogomils even formed the official Bosnian state church.

Excerpted and translated from: Hofmann, Tessa: Die Armenier: Schicksal, Kultur, Geschichte [The Armenians: Destiny, Culture, History]. Nürnberg: Verlag Das Andere, 1993, pp. 130-134

Destruction

As the Gazette de Lausanne reported on 6 July 1915, 50 Armenian notables were arrested in Divriği.[4] „After the arrest of the local Armenian elite, a second wave of arrest is organized upon the merchants and artisans of Divriği, upon which underage adolescents, comprising some 200 individuals, are mobilized. Submitted to torture for several days, these men are finally brought to the outskirts of the town, shackled, and forced to march to the gorges of Deren Dere, where they are assassinated with axes.”[5]

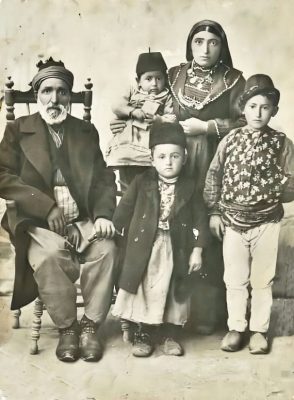

Khachig Karapetian (West Armenian: Garabedian), an Armenian official from Divriği born in 1888, was on vacation in his homeland with his family. On 6 December 1916, the Imperial German Consulate in Sivas reported that “according to the testimony of some workers of the road construction battalion from Armut-Dagh [Armut Dağı] near Divrigi [Divriği], Vilayet Sivas, Garabedian Khachig was housed for some time in the military and then civil prison in Sivas and was finally exiled with the other Armenians, with which batch it is no longer possible to determine. About the further fate of Garabedian and his family as well as where he was expelled, nothing more could be found out.”[6]

“On 28 May 1915 the inhabitants of the surrounding villages are first gathered at Divriği, where the men and youth from fourteen to eighteen years-of-age are separated from the others and imprisoned in a church before being executed. The remainder of the rural population is deported via Eğin (Akn) and Arapkir to Malatya and Fırıncılar.”[7]

“On 1 July 1915, the Armenian quarters of Divriği are surrounded by regular troops, who carry out the expulsion of the inhabitants, who are gathered near the southwest exit from the town, where they are put en route for Arapkir. Young women and girls are taken for the harems of local notables. The convoy is pillaged shortly after its departure near Sarı Çiçek by Kurdish villagers from nearby areas.”[8]

The kaza and town Divriği was also a transit area for deportees from other districts of Sivas province: Between 20 and 29 June 1915, around 7,000 Armenians of the kaza of Koçgiri/Zara are deported to Divriği, then Harput, Siverek, Urfa, Viranşehir, and Rakka.[9]