Toponym

The name of the kaza and its capital has evolved from the Greek Oinoe (pronounced Enoy) through Oinaion, Unieh, Unie and Unia to the current Ünye.

History

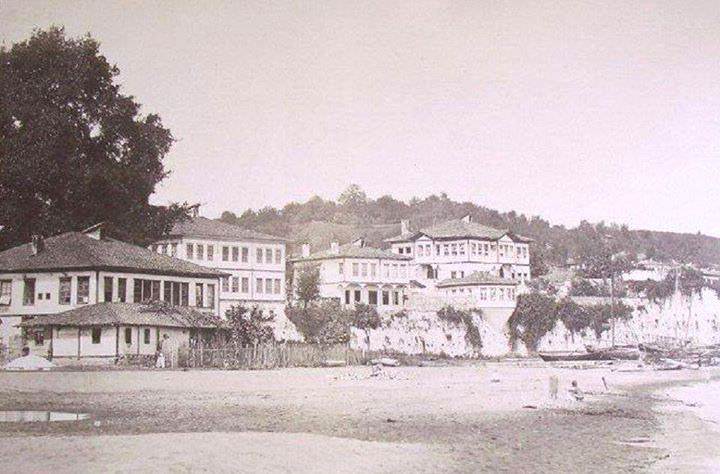

The history of the port town Ünye goes back to the Hittite period in the 15th century B.C., followed by the Kaskians (also Kashka, Kaska), Scythians, Milesians, Persians and Romans. During Greco-Roman times, it was called Oenoe and was a port town of Pontos, at the mouth of the river Genius.

It was also ruled by the Sultanate of Rum between 1188-1204, 1214-1228 and 1230-1243, the Empire of Trebizond in 1204-1214, 1228-1230, 1243-1297 and 1302-1346 and Emirate of Hacıemiroğlu between 1297-1302 and 1346-1461. During the 1290s, the Ünye fortress was built by the Trebizond emperor Ioanni (II).

It is believed the city was founded in the 5th century B.C. According to Pontic native D.I. Oeconomidis, Oinoy was also the seat of a sub-district of Pontos. Under the Komnenos Emperors it came to prominence virtually existing as its own hegemony.

Under Turkish rule the residents suffered a lot, in particular by Turkish demands but also by raids from Laz pirates. When the Laz attacked Ünye in 1806, this led to the town being evacuated under the guidance of Bishop Meletios. All the residents fled to Sinope, Russia or the Caucasus. The refugees to Sinope returned a few years later. In 1838 the city was completely destroyed by fire, and 1.500 Greek homes were burnt to the ground.[1]

Christian Population and Its Destruction

According to a 1911 statistical survey on ‘Greek villages in Pontos’, there lived 7,600 Greek Orthodox Christians in the kaza Ünye, in 19 communities, with 15 schools, and four ‘private churches’. 19 other churches were Catholic.[2]

In 1914 Ünye town had a population of around 10,000 of whom 2,500 were Greeks, 1,000 were Armenians and the remainder were Turks. The Greek community ran two mixed schools and a girls’ school. There were two parish churches in the city: Saint Nicholas and the Holy Trinity Church. According to the census of the Armenian Patriarchate at Constantinople, the Armenian community ran 14 churches and 21 schools in the kaza of Ünye.[3]

In 1916 Ottoman forces took 520 Greeks hostage and at the same time attacked armed Greek guerillas that had fortified themselves at the village Keris. After the guerillas escaped, Ottoman forces killed the hostages and burnt their villages. In 1917 the Greeks of Oinoy were deported to the interior to places such as Tokat, Sivas and Amasya where the majority perished from hunger and cold. The few that survived were expelled to Greece.[4]

Massacres, Deportation and Resistance of the Armenians in the Ünye Kaza

“In 1914, there were 7,700 Armenians in the kaza of Uniye [Trk.: Ünye]. A scant 700 lived in the seat of the kaza, the port of Uniye. The Armenian population was to be found, above all, in ten villages of the hinterland that were inhabited by stonecutters, weavers, and peasants, who cultivated tobacco and hazelnuts: Ozanı, Yamurcan, Eyrubeyli, Tekedamı, Düztarlan, Khachdur, Yusuflar/Köklük, Seylen, Gözderen, and Manasdere. (…)

Even before the deportation order was published, 25 notables from both the seat of the kaza and the villages were summoned to appear before the kaymakam, who had them imprisoned and then shot in Alaçami [Alaçam]. A survivor of the group, Zakar Tumanian, provides an account of what happened. The Armenians were deported in four caravans, with the exception of the village of Köklük, who were murdered there, and some old people who were allowed to remain in their homes. Approximately 150 people withdrew to the mountains under the leadership of Avedis Chakrian, Garabed Tahmazian, Kevork Koseyan, and Dikran Zeytunjian; they succeeded in saving a few deportees. (…) The unexpected arrival of two hundred Armenian resistance fighters from the neighboring regions of Fatsa, Çarşamba, and Bafra enabled the group from Uniye to resist. Several years later, under the Kemalist regime, these Armenians would be forced to leave the region for Abkhazia.”[5]