Greek Orthodox Population

The Orthodox metropolis of Amaseia was active until the compulsory Population exchange between Greece and Turkey (1923) and in 1922 counted c. 40,000 Greek Orthodox Christians, 20,000 of them being Greek speakers. Last active metropolitan bishop was Germanos Karavang(g)elis.

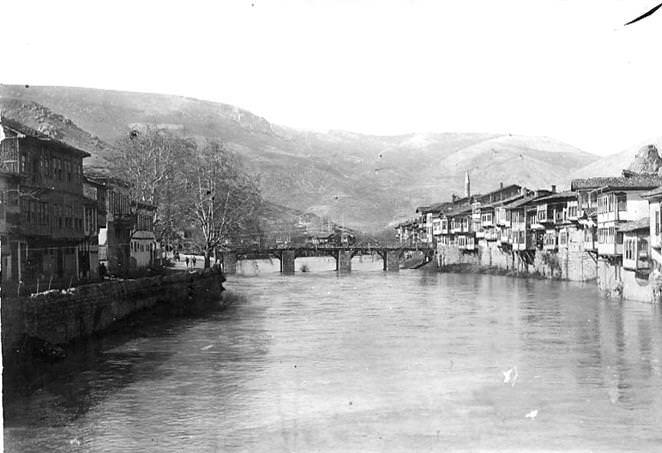

City of Amasya

Christian Population

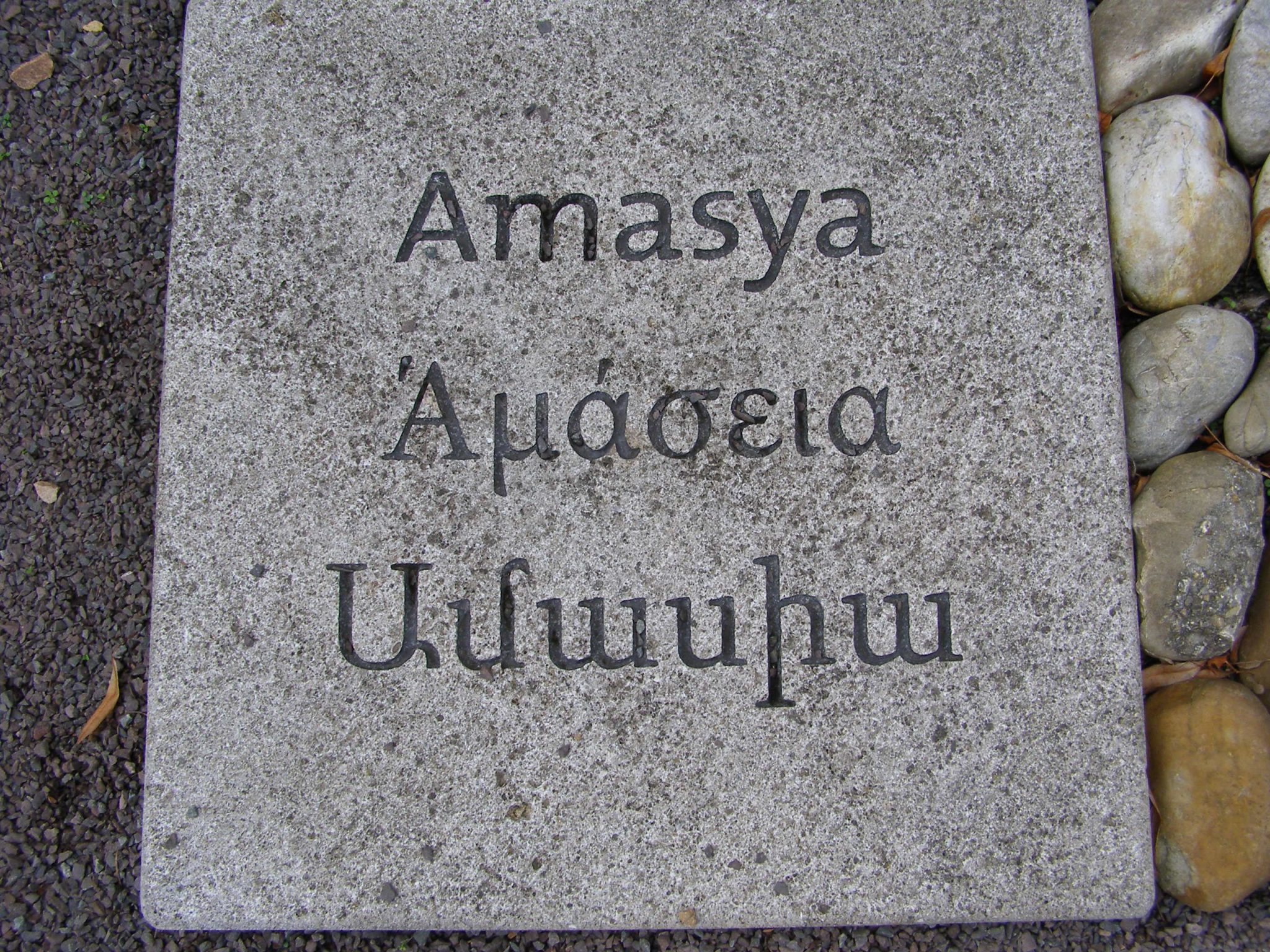

From the 12th century the Christian element was reduced due to the Turkic migrations into Anatolia. At the beginning of the 20th century, Amasya’s population reached about 30,000 people, more than 35% of whom were Armenians.[1]

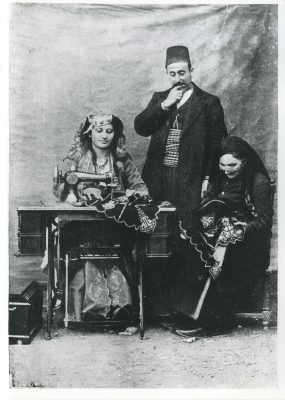

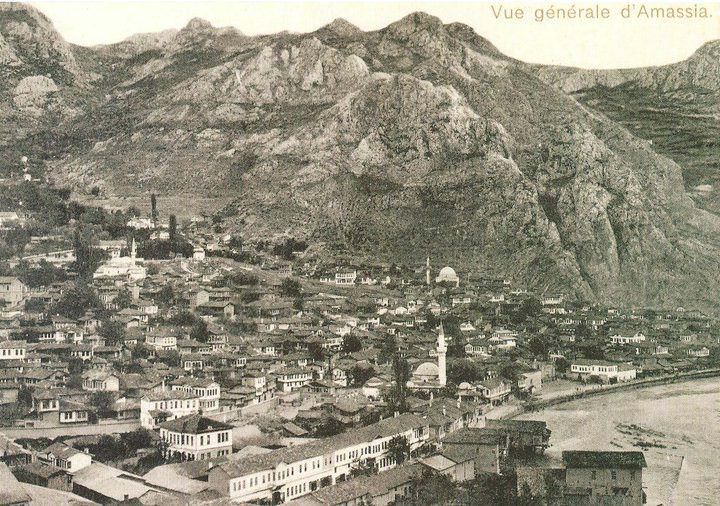

“In the kaza of Amasia, all 13,788 Armenians lived in the administrative seat of the kaza, also called Amasia, which was strung out in a narrow valley traversed by the Iris. The biggest Armenian neighborhood, known as Savayid, covered both slopes of a little dale. Located there were the Cathedral of Our Lady, the bishopric, the Church of Saint James, the Armenian hospital, the big Bartevian middle school, a Protestant Church, a Jesuit middle school, and an Armenian Catholic church. There was also a big Armenian population in the Deve neighborhood. Altogether there were 12 schools attended by more than 1,600 children. At the time, Amasia owed its prosperity in large measure by weaving, which the Armenians had partially mechanized.”[2]

The occupations of the people of Amasya included handicrafts, housework and manufacturing, trade, agriculture and gardening. The Armenians had 95 iron shops, carpentry, shoemaking, sewing, textile and tin workshops.[3] The four Armenian churches, among them Surb Hakob (Saint Jacob, built 1255) and Surb Karapet (Saint John), were famous for their antiquity and architecture. There were several places of pilgrimage and two monasteries in and around the city.

Notable Greeks and Armenians

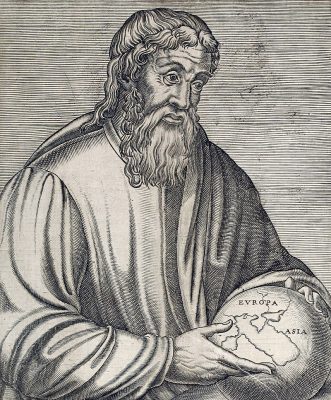

Strabo (c. 63 B.C. – c. 21/ 23 B.C.): Greek historian and geographer; he described his hometown in his work Geographika (12, 3, 39)

Amirdovlat of Amasia (c. 1420/25-1496): Armenian physician, bibliographer and lexicographer

Galust Amasiatsi: Armenian doctor who published his medical school in Constantinople in 1669

History

Archaeological research shows that Amasya was first settled by the Hittites and subsequently by Phrygians, Cimmerians, Lydians, Greeks, Persians, and Armenians. It is presumably identified with the Hittite settlement of Karakhana. In ancient times it was part of the Armenia Prima province of Lesser Armenia, and after the administrative transformation of Emperor Justinian (527-565) into the province of Armenia Secunda (Second Armenia).

Hellenistic period

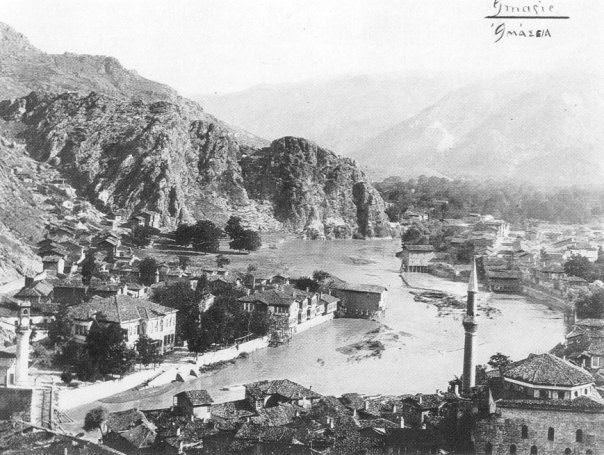

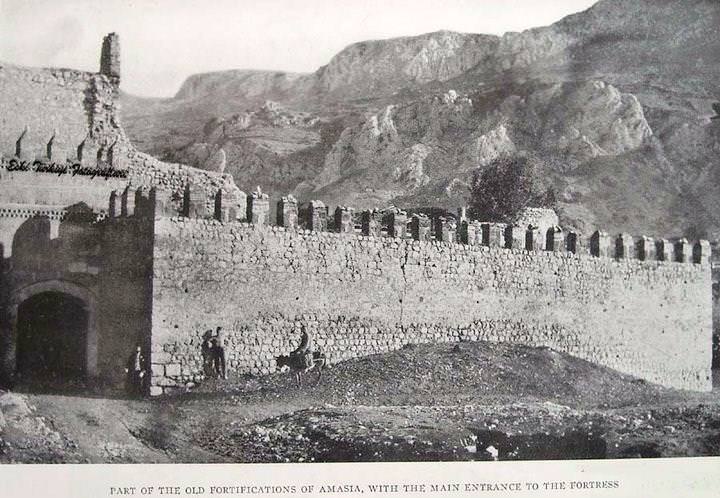

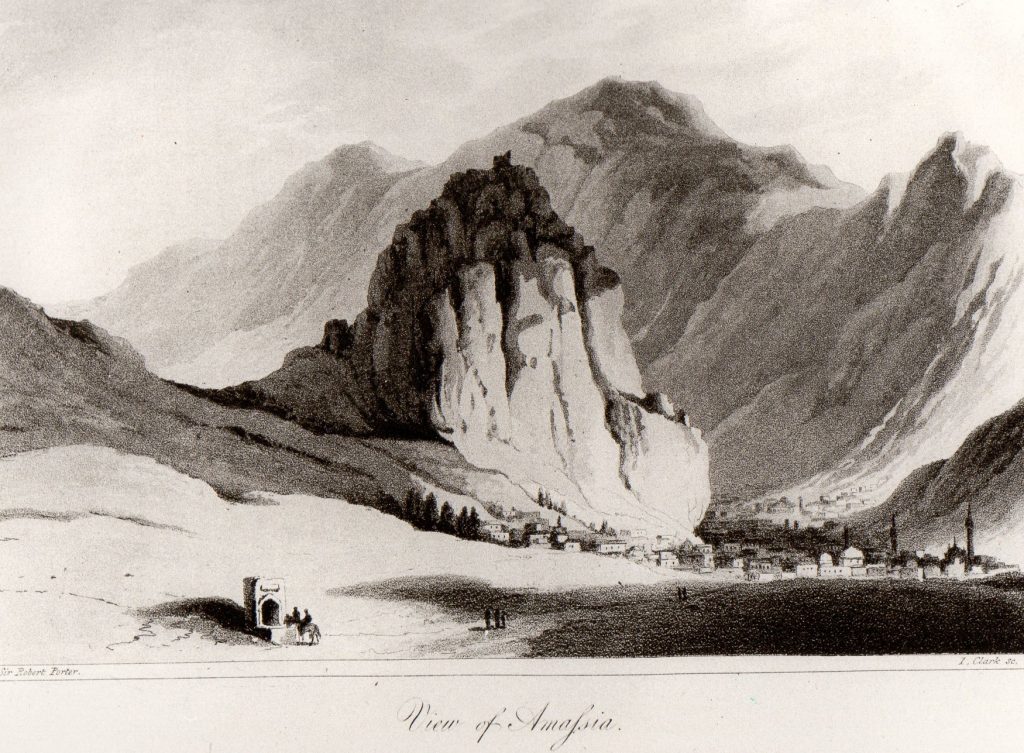

Historians attribute its founding to the time of Alexander the Great (4th century B.C.). They report that the city was built by order of Alexander the Great by his uncle Amasias. By 183 B.C., the city was settled by Hellenistic people, eventually becoming – from 333 to 26 B.C. – the capital of an independent Pontic kingdom, established by the Persian Mithridatic dynasty at the end of the 4th century B.C., in the wake of Alexander‘s conquests. Amasya was expanded and rebuilt by the Pontian ruler Mithridates VI Eupator (“good father”, 1st century B.C.), making it his capital. At that time Amasya was one of the most famous cities of Lesser Armenia. It was connected with Evdokia (Tokat), Sebastia (Sivas) and Harput (Mamuret ül-Aziz) by busy roads. Strabo writes that his hometown was a fortified city, surrounded by strong walls.

In the 1st century B.C., the Pontic Kingdom briefly contested Rome’s hegemony in Anatolia. Today, there are prominent ruins including the royal tombs of Pontos in the rocks above the riverbank in the city center.

Roman-Byzantine period

Amaseia was captured by a force led by the Roman Lucullus in 70 B.C. from Armenia and was quickly made a free city and administrative center of his new province of Bithynia and Pontus by Pompey. By this time, Amaseia was a thriving city, the home of thinkers, writers and poets, and one of them, Strabo, left a full description of of his native city, Amaseia, as it was between 60 B.C. and 19 A.D. Around 2 or 3 B.C., it was incorporated into the Roman province of Galatia, in the district of Pontus Galaticus. Around the year 112, the emperor Trajan designated it a part of the province of Cappadocia. Later in the 2nd century it gained the titles ‘metropolis‘ and ‘first city’. After the division of the Roman Empire by emperor Diocletian the city became part of the East Roman Empire (the Byzantine Empire). At this time, it had a predominantly Grekophone population.

Saints Theodore of Amaseia (died by 319), a warrior saint, and the local bishop Asterius of Amaseia (died c. 410), some of whose polished sermons survive, are notable Christian figures from the period.

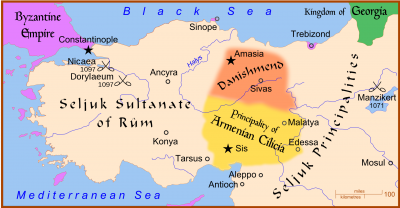

Early Turkish rulers

In 1075, ending 700 years of Byzantine rule, Amasya was conquered by the Turkmen Danishmend emirs. It served as their capital until the annexation of the Danishmendid dominions by the Seljuk ruler Kilic Arslan II. When he died, his realm was divided among his sons, and Amasya passed to Nizam ad-Din Arghun Shah. His rule was brief, as he lost it to his brother Rukn ad-Din Suleiman Shah, who subsequently became Sultan. During the 13th century the city passed under the control of the Mongol Ilkhanate, and was ruled by Mongol governors, except for a brief rule by Taj ad-Din Altintash, son of the last Seljuk sultan, Mesud II.

Under the Seljuks and the Ilkhan, the city became a center of Islamic culture and produced some notable individuals such as Yaqut al-Musta’simi (1221-1298) calligrapher and secretary of the last Abbasid caliph who was a Greek native of Amasya.

In 1341, the emir Habiloghlu occupied the city, before it came under the rule of the Eretnid emirate. Hadji Shadgeldi Pasha took Amasya from the Eretnids under Ali Bey. Shadgeldi was succeeded by his son Ahmed, who managed to retain his autonomy for a while, with Ottoman assistance; but in 1391/92, the mounting pressure forced him to cede the city to the Ottoman sultan Bayezid I, who installed his son, the future Mehmed I, as its governor.

Ottoman era

After the disastrous Battle of Ankara in 1402, Mehmed I fled to Amasya, which (along with nearby Tokat) became his main residence and stronghold during the Ottoman Interregnum.

As a result, the city enjoyed a special status under the Ottomans. A number of Ottoman princes were sent to the province of Amasya (the Rûm Eyalet) as governors in their youth, from Mehmed II in the late 14th century to Bayezid II in the 15th century, through to Murat III in the 16th century.

Suleiman the Magnificent often stayed in the city, and even received the Habsburg ambassador Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq there. Already distinguished as cultural center under the Seljuks, Amasya now “became one of the main seats of learning in Anatolia”.

In 1555, Amasya was the location for the signing of the Peace of Amasya with the Safavid dynasty of Persia, resulting in the first division of historical Armenia between Iran and the Ottoman Empire as the two rivaling regional hegemonial powers.

The population of Amasya at this time was very different from that of most other cities in the Ottoman Empire, as it was part of their training for the future sultans to learn about every nation of the Empire. Every millet of the Empire was represented in Amasya in a particular village—such as a Greek village, an Armenian village, a Bosnian village, a Tatar village, a Turkish village etc.

World War I and the Turkish War of Independence

In 1919 Amasya was the location of the final planning meetings held by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk for the building of a Turkish army to establish the Turkish republic following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War. It was here that Mustafa Kemal made the announcement of the Turkish War of Independence in the Amasya Circular. This circular is considered as the first written document putting the Turkish War of Independence in motion. The circular, distributed across Anatolia, declared Turkey’s independence and integrity to be in danger and called for a national conference to be held in Sivas (Sivas Congress) and before that, for a preparatory congress comprising representatives from the eastern provinces of Anatolia to be held in Erzurum in July (Erzurum Congress).

Ecclesiastical history

Amaseia became the seat of a Christian metropolitan bishop in the Eastern Roman Empire, in particular from the 3rd century A.D. As capital of the Late Roman province of Helenopontus, it also became its Metropolitan Archbishopric and included the suffragans of Amisos, Andrapa, Euchaitae, Ibora, Sinope, Zaliche and Zela. In the 10th century the metropolis ranked 11th among the metropolises of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. The Orthodox metropolis of Amasea was active until the compulsory Population exchange between Greece and Turkey (1923) and in 1922 counted c. 40,000 Christians, 20,000 of them being Greek speakers. Last active metropolitan bishop was Germanos Karavangelis.

Destruction

During the massacres of 1895/1896, more than 1,000 Armenians were killed.[4]

“In Amasia, after the deportation, the Armenian quarter, the bazaar, the Armenian church and the Greek church were set on fire by the Turks.”[5]

Konstantinos Fotiadis: The Martyrs of 1921

“The winter of 1920-1921 brought grave disasters for the Greeks of Pontos. The victories of the Greek army in the battlefields were to cost those left behind dearly. During this period, independence courts, which were actually more like medieval court-martials, sent most of the indicted to the gallows following summary proceedings. A careful selection was made prior to indictment. Outstanding individuals in the educational, economic, and political spheres were singled out for arrest.

On January 5, 1921, the Ankara government issued a decree ordering the closure of all Christian educational institutes, except the American ones. In Trebizond, for example, Kemalists ‘ordered the closure of all institutes and schools under the protection of the Allies, except the American orphanage. According to other sources, disorder occurred in the area, instigated by Kemal’s supporters’.

The head-mistress of the Greek girls’ school Eleni Dimitriadi, submitted the following report to the Ecumenical patriarch, about the hardships faced by Greeks in her area:

‘On January 18, 1921, a police patrol escorted by an armed military squad caught the whole district unawares, surrounding it on the pretext of conducting a house search. All the men were arrested, first and foremost His Eminence the assistant to the Metropolitan of Amasya, the now sanctified Efthymios, Bishop of Zela [Zile], whose memory lives on in our hearts, together with the blessed in memory Chancellor of the Holy Metropolitan Church, Plato Aivatzidis, and the remaining staff. All of them, including school directors, lay readers, directors of newspapers, clubs, associations etc., were first taken to the Samsun central prison under military escort. A few days later, they were moved to the Amasya central prison, which was a four-day journey from Samsun. There, following interrogation, which lasted for eight whole months and had been ordered by the court of independence, a verdict was issued by which they were condemned to death by hanging. (The death sentence was carried out on September 8, 1921.)’.

(…)

On January 31, 1921, all the members of Orpheus, the music and literature appreciation association of Upper Samsun, were charged with high treason and taken first to the prison of Samsun and then to that of Amasya, which was full of Greek intellectuals and merchants from Samsun, Bafra and Alacam. The new Kemalist extremes surpassed all previous atrocities, both in the violence inflicted, the number of victims, and the methods implemented.

From February 2-15, following Christ’s Reception Day, regular and irregular Kemalist army groups surrounded and besieged the Greek villages in the environs of Samsun, Amasya, Bafra, Erbaa and Merzifon with the aim of disarming all Greeks. The Turks ‘started to torment Christian families, so that they would betray those who had fled to the mountains.’

(…) Arrests of Greeks were followed by unfounded accusations of high treason and subsequent incarceration with a view to the ultimate confiscation of their fortunes.”[6]

“The central Independence Court of Pontos was situated in the inland city of Amasya, far from the coastal cities where consulates and international companies were based. For Mustafa Kemal, the Independence Courts ‘had a double target: firstly, to give a totally legal character to the annihilation of Asia Minor Greeks; secondly, to strike a lethal blow to Greek communities of the most flourishing towns by exterminating their outstanding members, a method much safer than deportation, as it allowed them no chances of survival. This last result was largely achieved, as hundreds of eminent civilians were hanged or shot mostly in Amasya, where the prison was crowded with renowned personalities of science and commerce from all areas of Pontos’.

Following the death of Tahsin Bey, the lawyer Emin, who was an ardent ‘persecutor of Christians’ and a parliamentary representative of Samsun, as well as Mustafa Kemal’s obedient instrument, was appointed president of the three-member committee. Summary court proceedings were extremely short. After doing away with the formality of the defense plea, the court announced its verdict, which was usually death by hanging. Only rarely were the accused sentenced to five, ten or fifteen years of imprisonment; and this was only done to provide the Kemalist judicial system with a façade of legality. Slander, lies, hypocrisy and mistrials were out of all proportion.”[7]

“The list of Pontian Greeks sentenced to death was much more extensive than similar lists from other areas. Most of them were hanged on the same day and time, September 8/21, 1921, in the Amasya square. Seventy-two Greek martyrs were led there and were mercilessly sacrificed. Most outstanding among them was archimandrite Plato, a brave and inspired old man, who chose to preach the Holy Word to his brothers for the last time and then moved on courageously to his end. The victims were sent to the gallows in groups of ten; the atrocious process went on until ten in the morning.”[8]

“Of those imprisoned, the Independent Court of Amasya sentenced to death by hanging: Mattheos Kofidis, former member of parliament, member of the Central Committee of Pontos and political commissioner; Alexandros G. Akritidis, manufacturer of spirits; Nikos Kapetanidis, owner of the newspaper Epochi; Georgios Th. Kakoulidis, Giresun merchant; Spiros I. Sourmelis, secretary of the metropolitan; merchants Iordanis I. Sourmelis, Ioannis K. Atmazidis and Ioannis P. Spathopoulos; Avraam Tokatlidis and Epameinondas Grigoriadis, citizens of Ordu. The following people were sentenced to death by hanging in absentia: Chrysanthos, Metropolitan of Trebizond; Lavrentios, Metropolitan of Chaldia and Giresun; K. G. Konstantinidis from Giresun, current resident of Marseilles; Aristotelis Neophytos, Mihail G. Mavridis, Pelopidas Kioridis, Haralampos Eleftheriadis, Aristidis Delikaris, Konstantinos Atmatzidis, Nikolaos Iasonidis, Leonidas Iasonidis, Lazaros Destapasidis, Georgios Mihailidis, Georgios Kalogeropoulos; Joachim, Bishop of Apollonias; Ioannis Eleftheriadis, Theodoros Emirzas; Polykarpos, Metropolitan of Neokesaria; Ordu doctor Haralampos; former manager of the Ottoman Bank Themistoklis Pastiadis; Pavlos Makridis, Konstantinos, son of the Church Warden Papa-Theodoros; and doctor Michail Galinos. The confiscation of the properties of those sentenced in absentia was also ordered.

Four months earlier, at the end of May [1921], the following had died in the prison of Amasya: the devout Bishop of Zela [Zile], Efthymios, assistant to Metropolitan Germanos Karavan(g)gelis; Vassilios Kalaitzis; and Andreas Kolaros, who died of typhus. Professor P. Valioulis, who survived the anguish of being condemned to death, described the methods used by the infamous Independence courts of Amasya.”[9]