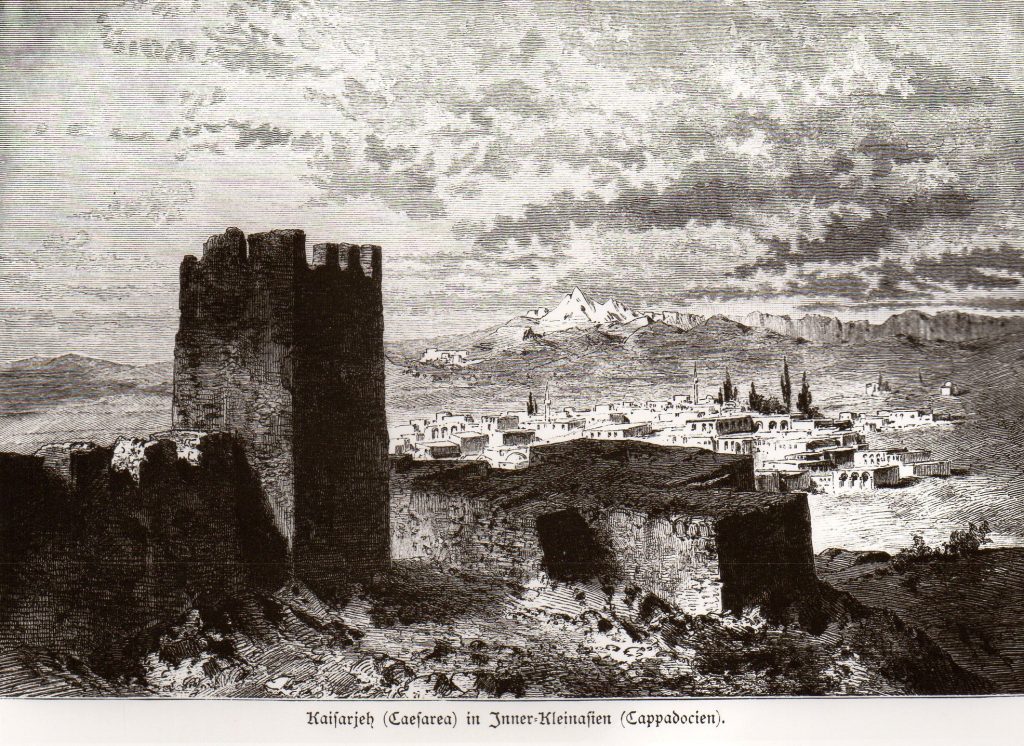

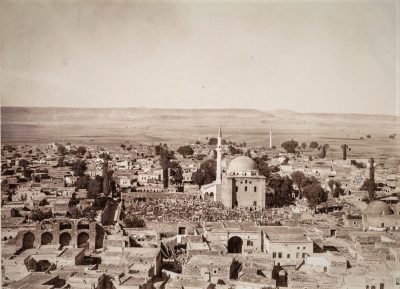

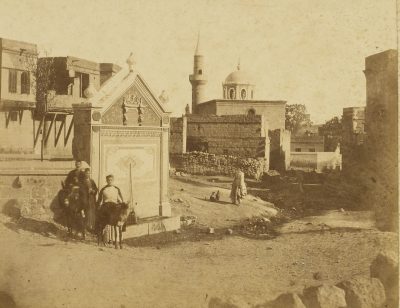

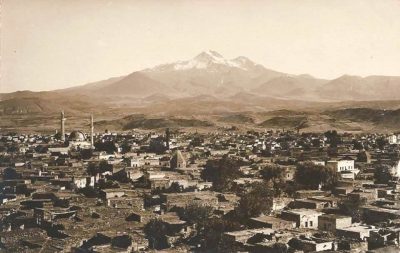

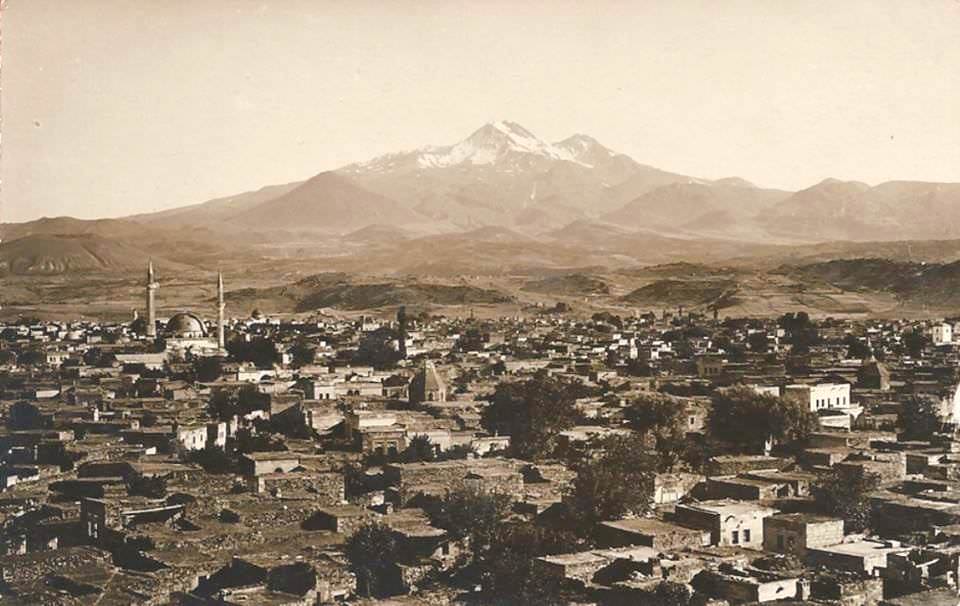

Mazaka / Caesarea / Kayseri City

Caesarea was an important trading center on the ancient Silk Road and home to many early Christian saints, such as the Basil of Caesarea, Andreas of Caesarea & Emmelia of Caesarea.

Toponym

Caesarea (Grk.: Καισάρεια) was historically known as Mazaka (ancient Grk.: Μάζακα; Armenian: Մաժաք Majak‘). The Armenian historiographer Movses of Khorene (Movses Khorenatsi) derives the toponym from Armenian ‘Mshak’, the name of a semi-legendary Armenian governor, who, according to Khorenatsi, built a dormitory here, covered it with walls and named it after him.

Population

“In the city of Kayseri, located in the central kaza, the 18,907 Armenians were concentrated in 28 of the city’s 114 neighborhoods in 1914, representing approximately 35 per cent of the total population. Cesarea’s economic importance hardly needs to be demonstrated. By this time, the city’s international trade had declined sharply, but this regression was partially compensated by Anatolian commerce. Gold-working, leather-tanning, and rug-making were especially thriving crafts.”[1]

History

The history of the city can be traced back to 3000 B.C.

Persian Capital

The ancient city of Mazaka was established on modern Beştepeler, just 1.5 km southwest of the current city center. Mazaka became a new settlement in the eighth century B.C., when the nearby trading colony, Kanesh Kültepe, collapsed. The city became prominent in the sixth century B.C. when the Persian Empire made Mazaka its capital for ruling over the empire’s new territories in Cappadocia. The Zoroastrian Persians were drawn to the volcanic mountain and natural flames.

Hellenization and Jews

Mazaka, with all of Anatolia, became Hellenized after Alexander the Great in 334 B.C. Alexander only passed through Cappadocia but his general, Perdiccas, later brought it under Greek rule. After Alexander’s death, Cappadocia was briefly part of the Seleucid Empire. Unlike Persian rule, Macedonian rule suppressed the local people and rulers. A revolt ensued and the previous family of rulers resumed the throne.

Independent Cappadocian kings, usually with the royal name Ariarathes, ruled the city of Mazaka for the next three centuries (301 B.C.–A.D. 17). Around 150 B.C., the Greek-loving King Ariarathes V renamed the city Eusebia in honor of his father. He made Mazaka and Tyana the main Greek cities of Cappadocia, as he hoped to Hellenize the unsophisticated region.

During this time, diasporic Jewish communities settled in the region. In 139 B.C., the Roman Senate wrote a circular letter to instruct rulers to protect Jews in their region (1 Maccabees 15). A copy was sent to Ariarathes V, king of Cappadocia. The Jews may have been resettled into the region by Seleucid rulers, or they may have come for commercial reasons, as Mazaka was an important trade center.

Romans

In 77 B.C., the Armenian King Tigran I sacked and deported the residents. A few decades later, the Romans entered Cappadocia. They liberated and reconstructed the city, so residents returned. The Romans administered Cappadocia through a series of client-kings based in Mazaka. Archelaus (36 BC–17 AD), who was the last independent Cappadocian king, renamed the city Caesarea to honor his patron in Rome, Caesar Augustus. The region minted many coins, which, from 10 B.C., bore the name Caesarea. When Archelaus died in A.D. 17, Tiberius eliminated the client-king arrangement and made Caesarea a Roman province. Rome appointed the ruling assembly (konion) and governor.

Successive Roman kings expanded the borders of Cappadocia, thus increasing the importance of its capital city, Caesarea. Augustus granted his loyal client, Archelaus, rule over eastern Cappadocia (Malatya) and Seleucia (Adana/Mersin). Vespasian combined Cappadocia with Galatia in A.D. 72. Then Hadrian added Pontos to the region. Caesarea had become the major city of eastern Anatolia. Temples, military posts, and a bath complex were constructed in Caesarea during the Roman imperial period. The city was an important transportation hub where five major Roman roads converged.

Christianity

Christianity entered Cappadocia in the first century, likely due to the apostle Peter’s ministry in the region (1 Peter 1:1). By A.D. 250, Caesarea was a metropolitan see with multiple bishops. Caesarea ranked alongside Antioch and Jerusalem in terms of ecclesiastical importance. The influential bishops Alexander (A.D. 200–15) and Firmilian (A.D. 230–265) led prominent church councils and hosted an influential training center.

The people of Caesarea suffered several calamities in the third century. A powerful earthquake destroyed the region in A.D. 232. The Roman governor blamed Christians for the natural disaster, alleging that their refusal to present sacrifices had angered the gods. As the Roman Empire weakened, raids by the Goths (254) and Persians (260) left Caesarea in ruins.

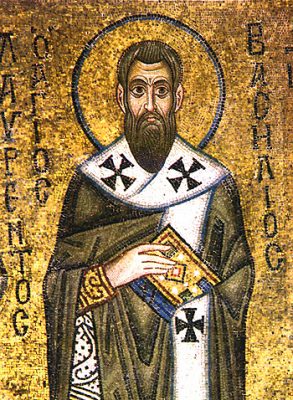

Basil and the New City

In 370, St. Basil the Great became bishop of Caesarea. The next year, a severe famine struck the region. Then, crafty businessmen hoarded grain to further inflate the price. Basil said the city “had fallen into an incredible condition … and no one visiting Caesarea, not even those most familiar with her, would recognize her as she is; to such complete abandonment has she been suddenly transformed … the city like a desert, a piteous spectacle to all who love it” (Letter 74). Basil’s summons for help, perhaps exaggerated to invoke pity, describes a dire situation.

The magistrates fled to Podandus (Pozantı) and the citizens continued to starve.

In response, Basil used his family fortune to construct the “Basiliad”—a massive humanitarian complex to feed the poor and heal the sick. The area in the open plain below the ancient city became so popular that Gregory of Nazianzus said it was another city. At that point, the city center of Caesarea transitioned from the hilltop (the now-abandoned Beştepeler) to its current location, as Basil’s humanitarian center attracted so many people.

Byzantine Era

In the early 500s, the Byzantine emperor Justinian built the black basalt citadel about the Basiliad. St. Basil’s Church attracted many pilgrims in the medieval age, as Caesarea lay near the famous Pilgrim’s Road from Constantinople to Jerusalem. As the Byzantine Empire weakened in the 600s and 700s, the Persian and Umayyad Empires repeatedly attacked Caesarea. The Byzantine Empire rebounded and the native Cappadocian military leader, Nikephoros II Phokas, declared himself the Byzantine emperor in Caesarea in 963. Then, in 1067, Seljuk Turks captured the city, which then became known as Kayseri.

Source: Cappadocia History https://www.cappadociahistory.com/post/caesarea-mazaca-kayseri

Caesarea / Kayseri in the Armenian Church History

“The city of Caeserea, today called Kayseri, has an important place in the history of the Armenian Church. Once the most important city in central Anatolia (…), it was where St. Gregory the Illuminator grew up, was educated, and became a Christian.

After his conversion of Trdat, king of Armenia, to Christianity in the early part of the 4th century, it was to Caeserea that St. Gregory returned to be formally ordained as a priest, and until the year 373 all the early catholicoi of Armenia were consecrated in Caeserea.”[2]

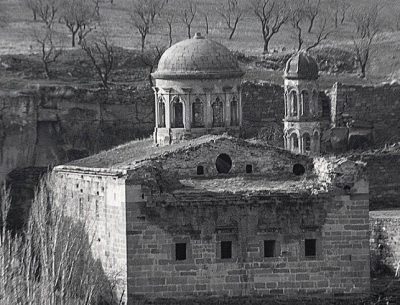

The still operating church dedicated to the Holy Illuminator of Armenia (Surb Grigor Lusavorich) recalls the importance that Caesarea/Kayseri had for Armenian church history. Today, the church is the only one in Eastern Anatolia that is sporadically used for worship.

“(…) the Armenian population of Kayseri has dwindled to almost nothing – if the surrounding villages and small towns are counted, there are now perhaps only 20 or 30 individuals left.

(…) Today there is no resident priest and services are no longer regularly conducted – but to prevent the confiscation of the church as abandoned property, priests travel from Istanbul several times a year to conduct services within it.

Until recently, few – if any – Armenians actually attended these services, but now pilgrimages to Kayseri by Armenians from Istanbul are often organized to coincide with the principle feast days of St. Gregory the Illuminator. Armenian visitors from abroad also sometimes attend.

Description

The church sits within a high walled enclosure that also contains many smaller ancillary buildings, mostly now derelict and roofless. The church is a relatively recent construction, being built in 1856. There are older dates on some of the surrounding buildings, so there was probably an older church on the same site. In the 1990s the interior was renovated, and the altars re-gilded.

The design of the church is a rectangular basilica with a nave and two aisles, The interior has 6 free-standing columns, 4 of which support a large cupola with a drum.

This design type is common in Armenian churches built from the

mid-17th century onwards, and was heavily influenced by post-Byzantine Greek churches. However, the standard design is altered here by having shallow rectangular arms that (on the lower level only) extend out from middle of the north and south sides of the church, giving the ground-plan of the church a cross shape. (…) The painting within the north altar is the most interesting. It depicts the vision of Saint Gregory: four columns of fire, with capitals of cloud, each surmounted by a flaming cross, carried arches that supported a dome of clouds, topped by a throne and the cross of Christ shimmering in divine light. In the painting, the artist makes an explicit connection between this vision and the traditional domed form of Armenian churches.”[3]

More information can be found on the website of the church foundation (in Turkish): http://www.kayserikilisesi.org/kilise-hakkinda.asp

Destruction

Local Armenians fell victim to state-organized massacres in Kayseri in 1895:

“The massacre in Kayseri began on November 30 [1895]. A rumor spread that ‘the Christians are killing the Mussulmans,’ provoking violence. Rioters rushed the markets and broke into houses. 308 Women were murdered in a public bath and men in a local factory. ‘There is ample evidence,’ wrote a Western correspondent and witness, ‘that the Government deliberately gave permission for plunder and murder to continue for four hours. Soldiers said so plainly.’ The number of dead was estimated at 500.”[4]

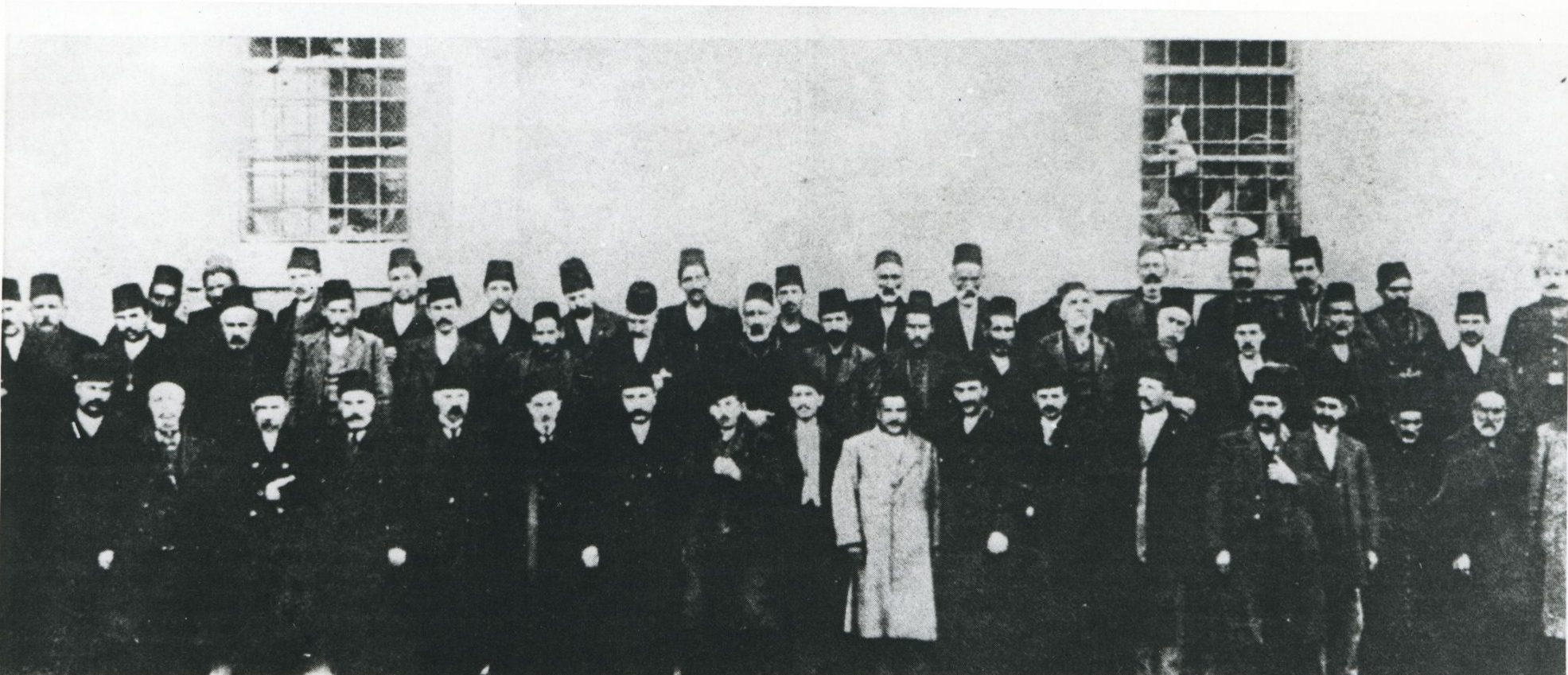

Front row, from left to right: A carpet dealer and hero from Gurin. Hovhannes Sungurlian. Karapet Sambakdjian. Barsegh Kilimian. Karapet Djamdjian. Nshan Haladjian. Yervand the lawyer. Garnik Kuyumdjian. Sungurlyan Jr. Varderes Armenian. Garnik Ughurlian. Avetis Sambakdjian. Grigor Geregmesian. Harutiun Ter Mkrtchian. Hakop Timurian. Barghasar the cobbler. Hovhannes. Dr. Levon Hunyakian. Second row, from left to right: Unknown. Garnik Balukdjian. Hakop Churakian. Hovhannes Ekmekdjian. Martiros Lussararian. Hakop Avsharian. Hakop Merdinian. The cobbler Karapet Navrusian. Nevshirlian. Vahan Kurkdjian. Coppersmith, shoemaker and grocer Daniel. Tekeh Ehyonian. Khacher. Iron smith. An unknown. Grigor Deukmedjian. Martiros Boyadjian. Third row, from left to right: Voskyan Minasian. An unknown. Garnik Djurdjurian. An unknown. Petros Matosian. Harutiun Boedjekian. Mihran the confectioner. Hakop Kherlian. Karapet Matosian. Karapet Elmadjian. Minas Minasian. Poghos Meshedjian. Hadji Miridjian. Tiran Ohanian. Karapet Istambolian. An Ottoman policeman. An unknown.

Source: Hushamatyan Mets Yegherni 1915-1965 (Beirut: Publishing House “Zartonk”, 1965, p. 352)

“In Kayseri, on June 13 [1915], the same day that the 21 Hnchakists were hanged in Constantinople, twelve Armenians who were members of political parties were sentenced to death. Already during May, 200 notables and Dashnaktsakan had been arrested. The Arajnort (Metropolitan) of Kayseri was also arrested and sentenced to death. Priests were beaten until they could no longer rise.

Any denunciation was enough to cause arrest. The villages around Kayseri (Incesu, Tomardze [Tomarza], Fenese) and others were emptied within a few hours.”[5]

“In February 1915, after a bomb exploded at the home of an Armenian activist in Kayseri, police conducted searches across the province. Scores of homemade bombs were found. As elsewhere, some were of recent manufacture or were freshly filled with explosives, but most were relics. The usual script then played out to its awful conclusion. First the government ordered Armenians to surrender their arms. But, recalling 1895–1896, when disarmament preceded slaughter, the Armenians hesitated. In response, there were further searches and more weapons found, most of them old guns. In late April Ottoman officials claimed to have found more bombs and some Martini rifles in an Armenian church. Armenian notables and activists were then rounded up. Under torture, a few admitted to collaborating with the Russians or to heading sabotage cells, but most of the detainees had nothing to do with revolutionary operations. The police then ordered the prisoners, and a few notables still walking free, to prepare for deportation to Diyarbekir. None finished the journey. Within three days of departure, the wagons returned empty, and word spread that they had been murdered. In August dozens of other notables—including a former parliamentary deputy, Hampartsoun Boyadjian—were tried for treason and hanged.

A few days later, fresh orders arrived instructing Kayseri officials to deport the province’s [kaza’s] entire Armenian community. They were given three days’ notice, then dispatched. Along the route they were joined by deportees from neighboring Talas and subjected routinely to robbery, abduction, and other abuses. In many cases, the men were first weeded out and murdered. Clara Richmond, a missionary in Talas, recounted that men and boys from a nearby village were locked in a church, bound in groups of five, taken out, and shot. Some villagers, who had heard of the massacres, resisted the gendarmes. ‘Most were slaughtered . . . by their Moslem neighbors,’ an unnamed missionary wrote. (…)

On September 5 Vali Zekai reported to the Interior Ministry that ‘a total of 49,947 Armenians, including Catholics and Protestants, were deported to Aleppo, Sham [Damascus] and Mosul from Kayseri‘. The vali and his men were exceedingly diligent: ‘Seven hundred and sixty . . . who were deported earlier but managed to escape and return and lived in hiding were also captured and sent back to exile,’ he told his superiors. The deportees included members of supposedly protected classes: some were ‘families of soldiers and others . . . Catholics and Protestants. These were dispersed in the villages at a ratio of 5% of the population.’ In November Armenian teachers in the American mission schools—a group that generally managed to pull strings and stay behind for a while—were deported.

Some Kayseri Armenians were initially saved by conversion. ‘We were told that it was in accordance with the principle that in the new Turkey, no Christian must be found,’ a local missionary explained. But the Security Directorate later decided that the option of lifesaving conversion had been granted too liberally. The Directorate warned Zekai that Armenians tended to convert only to save themselves and instructed him not to hesitate to deport converts. The situation was different for younger converts, who could be forcibly integrated in Muslim communities. Many children in Kayseri were taken to government orphanages and circumcised.”[6]

“In Derevank, half an hour from Talas near Kayseri, three deserters had been hiding, one with his wife, and had not been extradited. As punishment, the whole population was deported and all their belongings were sold. All belongings were piled up in the church, even the children’s shoes, and were offered for sale there. For what was worth 100 piasters, a price of about five piasters was obtained.”[7]

Kemalist deportations and massacre

In 1919 and May 1921, Greek Orthodox children and adults were deported to Sivas (1919) and Bitlis (May 1921). The Near East Relief (NER) physician Mark Hopkins Ward noted the following deportations of Christians from Kayseri: On 26 May 1921, ten Greeks and six Armenians from Kayseri, Konya and Amasya were sent to Elazığ, Diyarbekir, then Bitlis, followed by 125 men from Konya, Karaman, Eregli, Nigde and Kayseri, who were deported to Bitlis via Elazığ on 28 September 1921. A third convoy to Bitlis of 1,400 (originally 2,500, when they left Kayseri) deportees left Harput on 13 December 1921; the deportees were from Ordu, Giresun, Amasya, Isparta, Burdur, and ‘Endemish’ [Edremit?].[8]

More frequent deportations of Greeks to Kayseri took place in 1919, 1920 and 1922. The deportees came from Güllük, Izmir, Isparta, Nazilli, Denizli, Darsiyak, Aksaray (originally from Honaz), Burdur and Arkarasu. These were mainly deportations of Greek Orthodox men.[9]

In March 1921, Kemalist forces committed “a terrible” 3 days massacre of Christians in Kayseri.[10]