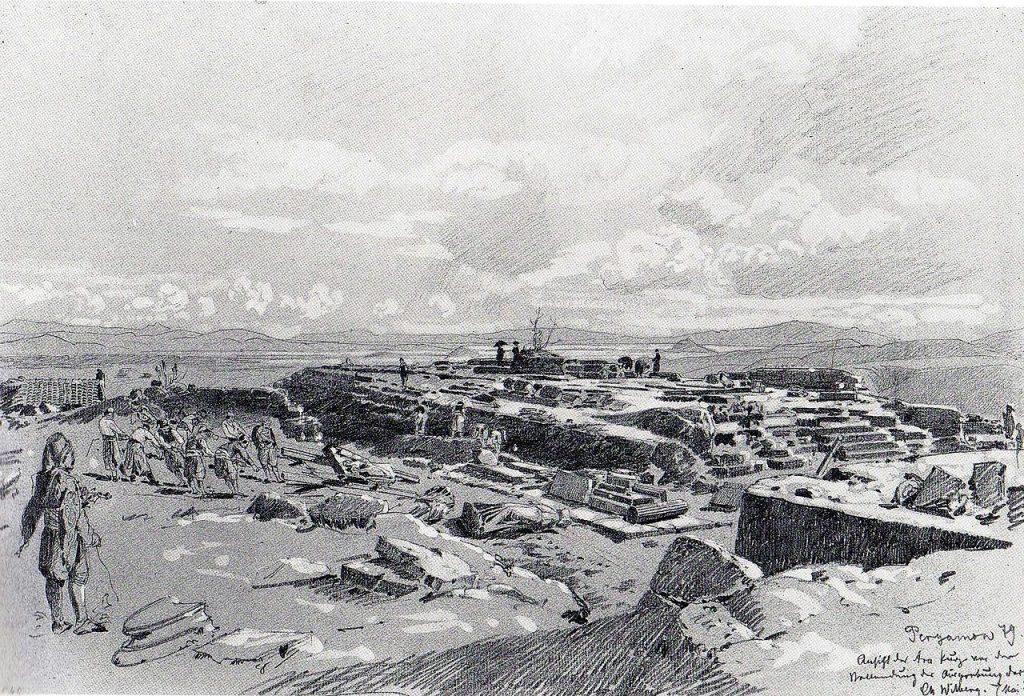

Pergamon was located on the northern edge of a plain formed by the river Kaïkos (today’s Bakırçay). The built-up area rises at the feet, on the slopes and on the plateau of the Acropolis, the core of which consists of a mesa-shaped massif of andesite rock about 335 meters high. The castle hill slopes very steeply to the north, east and west, while the southern side forms a flatter transition to the plain via three natural steps. To the west, the Selinos (today Bergamaçay) flows through the city past the Acropolis, while to the east flows the Ketios (today Kestelçay).

Toponym

The place-name Bergama, as well as its ancient predecessor Pergamon, are thought to be connected with the even more ancient Luwian language adjective ‘parrai’ (Hittite language equivalent; ‘parku’), meaning ‘high’. The ancient and modern Greek language form of the name is Πέργαμος – Pergamos. In Turkish language, it has been adapted to Bergama.

Christian Population

Ecclesiastically, the Greek population of the kaza of Bergama belonged to the Diocese of Kúzikos (Grk.: Κύζικος) with a population of 41,331 Greek Orthodox Christians in 43 communities.[1]

The Armenian population of the kaza of Bergama numbered one-thousand before their deportation in 1915.[2]

History

Pre-Hellenistic Period

The settlement of Pergamon can certainly be proven for the Archaic period, but the findings are few and are mainly based on finds of fragments of Western imported pottery of Eastern Greek and Corinthian provenance, dating from the late 8th century B.C. Pergamon is first mentioned in literature for the year 400/399 B.C., as the march of the ten thousand, the so-called Anabasis, ended in Pergamon. Xenophon, who names the city Pergamos, handed over here in March 399 B.C. the remnants of the Greek mercenary army – according to Diodorus about 5 000 men – to the Spartan general Thibron, who was planning a campaign against Tissaphernes and Pharnabazos. At that time Pergamon was owned by the family of Gongyles from Eretria. In 362 B.C., one Orontes, satrap in Mysia, tried to achieve independence in Pergamon. It was not until Alexander the Great that this area, and with it Pergamon, became independent from Persian domination. Traces of the pre-Hellenistic settlement of the 4th century B.C. are rare, since in the following times the terrain was again and again profoundly reshaped and in the course of large-scale terracing older building fabric was mostly completely removed. The temple of Athena, for example, can be traced back to the 4th century B.C., but there is also evidence of altar foundations and walls of the 4th century B.C. in the Demeter sanctuary.

Hellenistic period

At the time of the Diadochoi, Pergamon, like the rest of Mysia, belonged to the domain of Lysimachos. He appointed Philetairos as guardian of the castle, where a large part of Lysimachos’ war booty, 9,000 talents, was deposited. With this treasure, Philetairos succeeded in becoming independent after the death of Lysimachos in 281 B.C. and in founding his own dynasty with the Attalids.

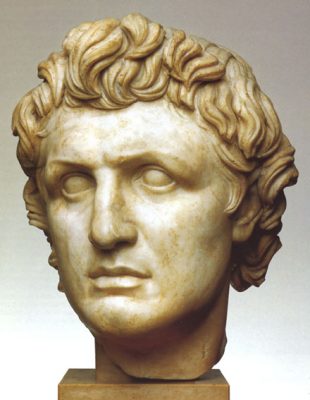

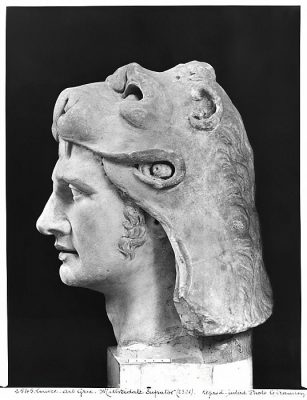

The Attalids ruled Pergamon from 281 to 133 B.C.: While Philetairos’ territory was still limited to the immediate vicinity of the city, Eumenes I extended his claim and territory. Especially after the Battle of Sardis in 261 B.C. against Antiochos I Soter, Eumenes appropriated the territories up to the coast and parts of the inland hinterland. The city thus became the center of the Pergamene Empire. Eumenes I did not yet take the title of king. This was done only by his successor Attalos I Soter, after he had defeated the Galatians, to whom Pergamon under Eumenes I was tributary. Only now there was an independent Pergamene Empire, which reached the peak of its power and expansion in 188 B.C.

Since the reign of Attalos I, the Attalids were among the most loyal supporters of Rome among the Hellenistic successor states. They sided with Rome against Philip V of Macedonia during the First and Second Macedonian Wars. With their 201 B.C. request to Rome for help against Philip V, the Attalids, along with Rhodes, were one of the triggers of the Second War against Philip.

Pergamon was also part of the Roman-Greek coalition in the Roman-Syrian War against the Seleucid Antiochos III, and after the Peace of Apameia in 188 B.C. was granted large parts of the Seleucid’s Asia Minor territory.

Eumenes II also supported Rome in the Third Macedonian-Roman War against Perseus. Rome did not thank its ally. Based on a rumor that Pergamon had negotiated with Perseus during the war, Rome wanted Attalos II to replace Eumenes II as regent, which the latter rejected. As a result, Pergamon lost its privileged status in Rome and was not granted any further territories.

Under the brothers Eumenes II and Attalos II, Pergamon experienced its heyday, which was reflected in the monumental expansion of the city. The aim was to create a second Athens, an Athens of artistic and cultural activity, as it was in the time of Pericles and dominated large parts of Greek art. The two brothers were the most pronounced witnesses of a trait of the Attalids that was rare in this form among the Hellenistic dynasties: a pronounced sense of family that knew neither competition nor intrigue.

Attalos III of Pergamon, who died without descendants in 133 B.C., bequeathed Pergamon to the Romans. However, the Romans first had to fight off the rebellion of Aristonikos in order to be able to take over their inheritance. This succeeded only in 129 B.C. From the kingdom of Pergamon arose the Roman province Asia, the city itself was declared free.

Roman period

In 88 B.C. Mithridates VI chose the city as his headquarters in the First Mithridatic War against Rome. The consequences of this war led to a stagnation in the development and expansion of the city. Pergamon lost all benefits and the status of a free city after the end of the war as an apostate city. Instead, the city was now subject to tribute, had to pay for the accommodation and food of the Roman troops, and the assets of many inhabitants were confiscated. Members of the Pergamene aristocracy in particular, who maintained excellent relations with Rome, acted as benefactors of the city with their own wealth, most notably Diodoros Pasparos in the 70s B.C. Through his diplomatic skills, he succeeded in alleviating many of the new burdens or having them abolished. Numerous honorary inscriptions found in Pergamon bear witness to his work and his outstanding position in Pergamon at that time.

Nevertheless, Pergamon remained highly famous and the proverbial delights of Lucullus were imported goods from this very city, which received a conventus, the seat of a judicial district. Under Augustus, the first imperial cult, a neocoria, was established in Pergamon in the province of Asia. Neokoros (ancient Greek νεωκόρος ‘temple keeper’; plural neokoroi) was the name given in ancient Greece to officials who supervised a temple. Under the Roman emperors, in whose imperial cult neokoroi were also appointed as priests, their office was an honorary one. Entire cities in the east of the empire also received the title of neokoros on coins and in inscriptions if they had erected a temple to the emperor. In some provinces (such as Asia) there was a competition between the cities to see which of them had acquired the most neocoria.

Pliny the Elder considered Pergamon the most important of the cities in the province, and the local aristocracy continued to produce outstanding men, such as the two-time consul Gaius Antius Aulus Iulius Quadratus in the 1st century AD. The pseudo-autonomous status of the city was underlined by its own coinage. On the coins, however, there is often a bust of Roma, which made clear the subordination to Roman interests.

But it was not until the reign of Traian and his successors that the city underwent a comprehensive reorganization, the construction of a Roman “new city” at the foot of the Acropolis, and Pergamon was the first city in the province to receive a second neocoria from Traian in 113/114 A.D. Hadrian elevated the city to the rank of metropolis in 123 A.D., thus distinguishing it from its competitors Ephesus and Smyrna. In the middle of the 2nd century, Pergamon was the largest city in the province next to these two and had about 200,000 inhabitants. Caracalla gave the city a third neocory, but decline was already setting in. Finally, under the soldier-emperors, the economic power of Pergamon waned, and it visibly lost its importance and was threatened by invasions of the Goths. In late antiquity there was a limited economic recovery.

Byzantine period

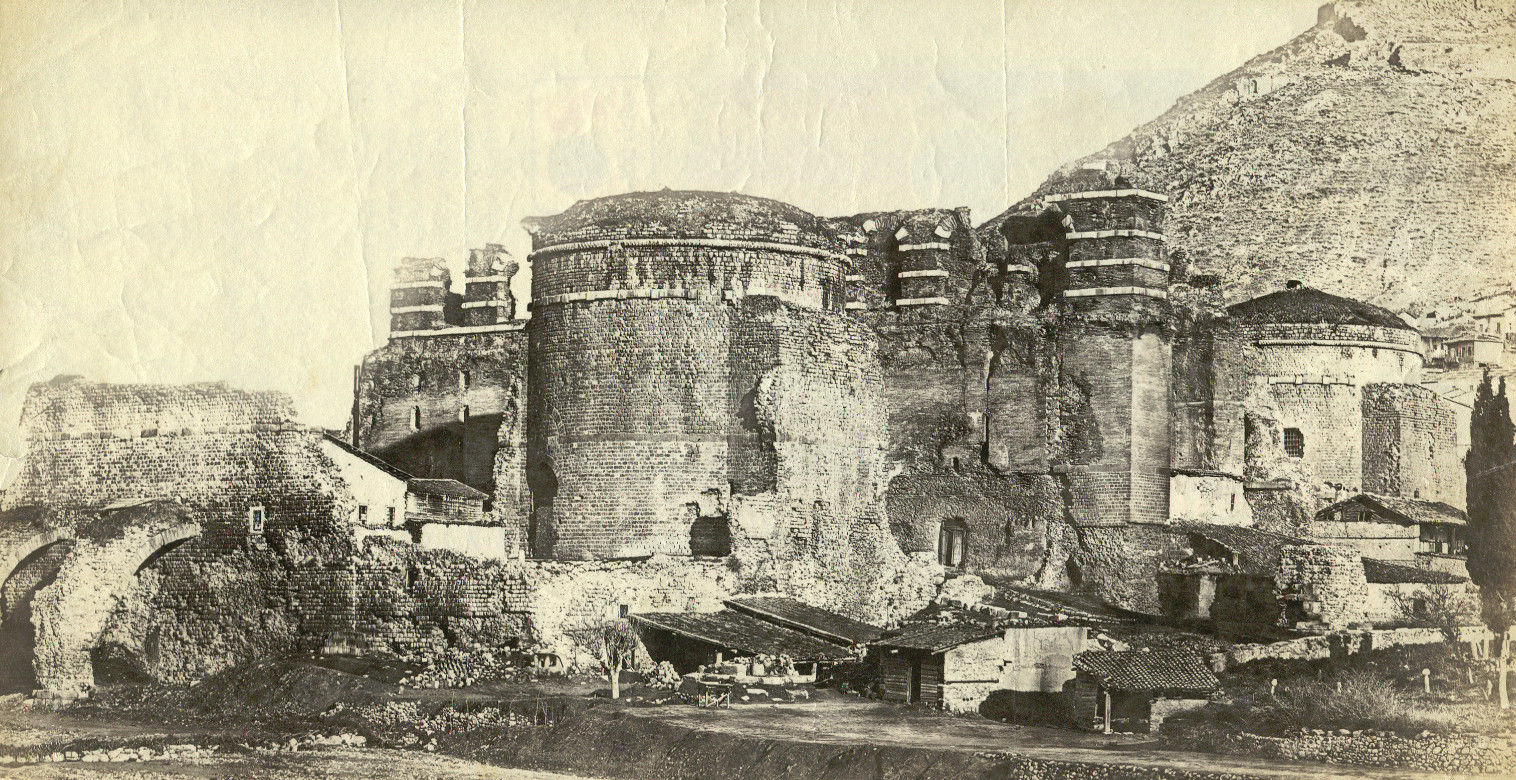

In 663/664 A.D., Pergamon fell for the first time into the hands of the Islamic Arabs who conquered Asia Minor. And so, in the Byzantine period, it is possible to trace a retreat of the settlement to the castle hill, which was protected by a 6-meter thick wall built of spolia. Pergamon, seat of one of the seven oldest main churches in Asia Minor, was conquered again in 716 by the Arabs under Maslama ibn Abd-al-Malik, and large parts of the population were destroyed. The city was subsequently rebuilt and fortified after the Arabs abandoned their attempt to conquer Constantinople (717-718).

Under Leo III, Pergamon belonged to the Thracian thema, and since Leo VI to the Samos subject. It suffered during the advance of the Turkish Seljuks into western Anatolia after the Battle of Mantzikert in 1071, but remained a prosperous city under the Byzantine dynasty of the Komneni. Under Isaac II Angelos, the place became an archbishopric, having previously been a suffragan bishopric of Ephesus. After the conquest of Constantinople in 1204 in the Fourth Crusade, Pergamon became part of the Empire of Nikaia.

When the future Emperor Theodoros II Laskaris visited Pergamon around 1250, he was shown the house of the ancient Greek scholar and physician Galenos (b. 129 A.D.), but he saw the theaters of the city destroyed, and apart from the walls, to which he paid some attention, only the overhangs of the Selinus River were worth mentioning. The splendorous buildings of the Attalids and the Romans were by this time only plundered ruins. In 1345 Pergamon finally became part of the Ottoman Empire.

Ottoman Era

After the Turks migrated to Asia Minor around 1300, Bergama belonged to the Beylik Karesi. When the Ottomans under Sultan Orhan I annexed the Beylik, the city became the judicial district (kaza) of the sancak Hudāwendigār (Bursa) in Eyâlet Anatolia, and later of the sancak Smyrna in the Vilâyet of Aydın. After the Battle of Bergama, Hellenic troops occupied the city in 1919-1922, but it lost its Greek inhabitants during the forced population exchange after the Treaty of Lausanne and was settled by resettled Turks from Greece.

Bergama- Pergamon

Pergamon is one of the Seven Churches of Revelation. This ancient city had a Library of 200.000 books and is famous for the invention of the parchment. Amongst the archaeological remains there is the Zeus Altar which was compared to the Altar of Devil by St. John and of which a great part is at the Berlin Museum and a copy in Rome. There is also the Theater and the Red Basilica the former Temple of Egyptian Gods the Red Basilica which was dedicated to St. John and became the symbol of the Pergamon Church. In addition to that although the people of this region preferred Theaters due its love for play, music an dance there is an interesting Amphitheater and a Gladiator School.

Galenus (129-250) who will be the physician of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius and of the Gladiator School made together with the Asklepion the Health Center of Pergamon such a fame that the Smyrniot orator Aristide (117-189) said “I owe my entire life to you, Asklepios, and I am deeply commited to you with a mysterious love”. When the kings of Pergamon the Attalids granted Pergamon to the Romans there had been many marriages between the Pergamon kings descents and benefactors of the city with the nobles Romans, This can be considered as the first levantine movement in the region. The Pergamian Quadratos were assigned as Governors of provinces as well as commanders in the Rome Army. The roman Governor Starzio Quadrato who condemned St. Polycarp of Smyrna as well as according to a legend Alexander Mavrocordato who signed the treaty of Karlowitz in the name of the Ottoman Empire were also from this Quadrato family.

Excerpted from: “Neighborhoods” – http://levantineheritage.com/

Destruction

Since the Balkan Wars of 1912/13, the Diocese of Kuzikos “failed to escape the fatal consequences of boycott and deportation. Turkish bands engaged for the purpose visited the villages and prevented the customers from entering Greek shops, while preachers from the top of the minarets incited the Turks to take even severer steps for making the boycott more efficacious. The communities of Balikesser [Balıkesir; Karesi until 1926], Sikaminea, Geltze, Diavati, Upper and Lower Neohori, and Smavlo, suffered from the boycott as well as from plundering and persecutions carried on in the very presence of the Government officials. Artaki, Sidirye, Pandemia, and Balia fared none the better.

It is a remarkable fact that, despite the promises made by the Minister of the Interior, Talaat Bey, to the Christian population of Panderma [Bandırma; Grk: Panormos] that he would stop the boycott, it was applied with even greater severity each time, proving the duplicity of the Turks in their dealings with the Christian populations.”[3]

1914

“The sub-governor of Pergamos installed Turkish immigrants in the Christian houses, who daily terrorised the inhabitants. This also happened to the other villages. At Klisse-keuy [Kiliseköy] the family of Christo Tsaghari, composed of six members, was assassinated. Mallis and Prokopios Theodosiou, notable natives of Scala Klisse-keuy, were also assassinated. The wife of the latter was carried away to the mountains by the marauders. On the 28th of May, numerous Turks assailed the village of Soghandjilar [Soğancilar], and wounded a woman and her child of a year old, also Michel Bali. They then went to the village of Kalarya, and committed the same crimes there. The Turkish immigrants established at Christianohori joined the Moslems of the surrounding country, and expelled the Christian inhabitants of the village, who were compelled to take refuge at Kiniki, in a miserable condition. Driven away from there by the Mudir, they went to Pergamus, but the gendarmes prevented them from entering the village, so that they passed the night in the open air. The day after they sought refuge in Dikeli.”[4]

Deportation in 1915

In September 1915, Bergama was destroyed by fire and evacuated.[5]

Elias Venezis: Murder of a priest in Pergamon (October 1922)

Elias Venezis (i.e. Mellos; 1904-1973), a subsequent Greek author born in Ayvalik, was deported to Manisa via Bergama as a forced laborer along with other Greeks in October 1922. In his memoirs, written close to the event, he describes, among other things, the murder of a 72-year-old Greek Orthodox priest from Ayvalik in Bergama:

“The popes had traveled the same route one day after us. We asked them for news. They did not get to report to us. The escort appeared. They told us to stand up and march on. We had recovered somewhat from the night’s sleep and the bread. But the priests were deplorable. Especially the two of them did not want to get up. They were forced to do so.

We set out on our way. On the left, the Acropolis of Pergamon shone – Attalos III, who was being divorced from his wife…

The train stopped. A confusion. The soldiers cursed, shouted. The old Pope did not want to go on. He fell. Support him two by two under the arms!, the leader ordered. Two of us grabbed him under the armpits and moved on. But his feet lagged behind, dragging. We stopped again. The sergeant came up from behind, beside himself. With the barrel of the rifle he gave him a few jerks in the hip to bring him to. He became heavy, slipped from our hands and fell down. The soldiers looked him up and down, dragged him to the side of the road, dropped him on his face and hit him with the butt. He did not even moan. Only with his tongue he licked the earth, as if he wanted to try whether it was salty or bitter.

From the hill, opposite the castle of Attalos, a few meters away from us, Turkish children who were playing there slipped down into the scene. The soldiers retreated to continue marching. The children all together began to throw stones from close by at the body that was breathing its last.

For a while we could still hear the dull thud of the stones as they piled up more and more. He had given me Holy Communion three times when I was small.

Excerpted and translated into English from: Venesis, Elias: Nr. 31328. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, (1969), p. 74f.