The town Chrysopolis was an ancient place on the eastern shore of the Bosphorus opposite Constantinople. Its port had great importance in ancient times, as well as in the Byzantine and Ottoman periods, as one of the most important crossings between Asia Minor and Europe.

Although it was called ‘the greatest city of the Occident’ by Emperor Justinian I, it was never a polis despite this designation, but a part of the city of Chalcedon.

Toponym

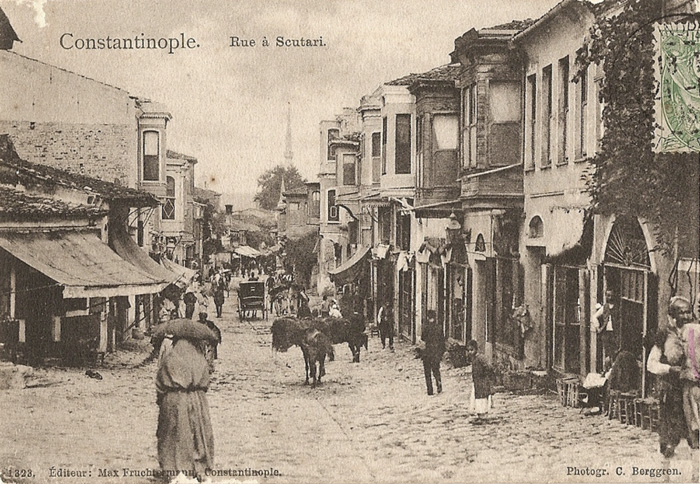

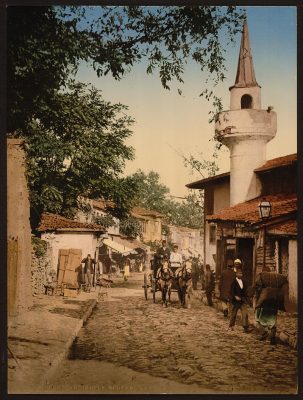

In ancient times, the eponymous main and administrative town was called Chrysopolis (Greek Χρυσόπολις, “golden city”), later Escutari, Scutarion or Scutari (‘raw tanned leather’), from which the present name Üsküdar is derived. The toponym Scutarion may have been used to describe the scutum shields that guards used that were made of leather.

The meaning of the name Chrysopolis could not be explained with certainty even in ancient times. According to an ancient Greek geographer, the city received the name Chrysopolis because the Persian empire had a gold depository there or because it was associated with Agamemnon and Chryseis‘ son, Chryses. On the other hand, according to an 18th-century writer, it received the name because of the excellence of its harbor.

Administration

The sancak existed from 1867 to 1922 within the province of Constantinople.

Population

Ecclestically, the Greek Orthodox residents of the sancak of Üsküdar belonged to the Diocese of Chalcedon (Trk.: Kadiköy), numbering 63,557 inhabitants in thirty-four communities.[1]

Notable Christians, born in Chrysopolis / Scutari / Üsküdar

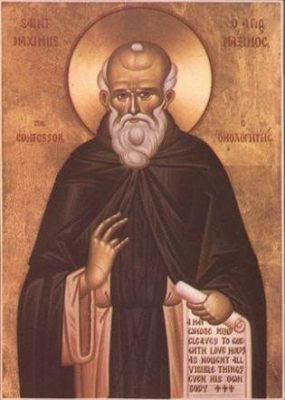

- Maximus the Confessor (Μάξιμος ὁ Ὁμολογητής, born c. 580 – Tsageri/Georgia,13 August 662), also known as Maximus the Theologian and Maximus of Constantinople; Byzantine monk, theologian and scholar. He entered a monastery in Chrysopolis in the early 7th century.

- Philippicus (Φιλιππικός – Filippikos, fl. 580s–610s), Byzantine general; a monk in Chrysopolis between 602–610, and buried in Chrysopolis

- Sergius I of Constantinople (Σέργιος Α΄, Sergios I; d. 9 December 638 in Constantinople), Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.

- Patriarch Pyrrhus of Constantinople (? – 1 June 654), ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople from 20 December 638 to 29 September 641, and again from 9 January to 1 June 654

- Alexios Mosele (Ἀλέξιος Μωσηλέ), Byzantine aristocrat and general

- Michael III (Μιχαήλ; January 840 – 24 September 867), Byzantine Emperor from 842 to 867

- Xenophon Sideridis (Ξενοφών Σιδερίδης – Xenofón Siderídis, born April 1851, Üsküdar – died 15 August 1929, Athens), Greek historian, writer and researcher

- Zabel Sibil Asadour (Զապէլ Ասատուր – Zapel Asatur; Pseudonym Սիպիլ – Sipil / Sibil; born as Զապէլ Խանճեան – Zapel Khanjian, 23 July 1863, Üsküdar – 19 June 1934), Armenian poet, writer, publisher, educator and philanthropist

- Calouste Sarkis Gulbenkian (Գալուստ Կիւլպէնկեան – Galust Kulpenkian, nicknamed ‘Mister Five Percent’, 23 March 1869, Üsküdar – 20 July 1955, Lisbon), Armenian businessman and philanthropist, once the richest man in the world

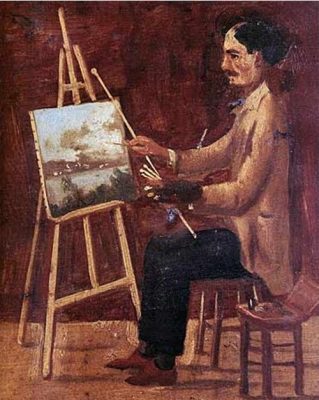

- Garabet Yazmaciyan(Կարապետ Եազմաճեան – Karapet Yazmajian; 1868-1929), Armenian painter

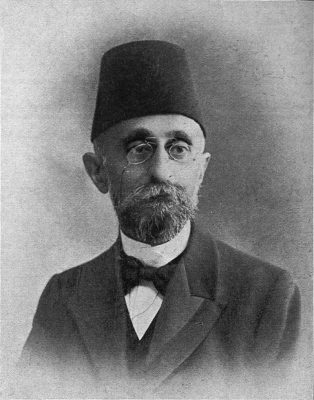

- Gabriel Noradunkian (Գաբրիել Նորադունքեան; 6 November 1852 Constantinople – 1936 Paris) – Ottoman Armenian politician

- Yeghishe Durian (Եղիշե Դուրյան; born Mihran Durian; also Dourian, Tourian; 23 February 1860 – 27 April 1930), Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem and Constantinople

- Petros Durian (Պետրոս Դուրյան, also Dourian, Tourian; brother of Yeghishe Durian; 1851-1872), Armenian poet

- Hovhannes Hintliyan (Յովհաննէս Հինդլիեան – Howhannes Hindliyan, Üsküdar, 1866 – 16 March 1950, Istanbul), Armenian pedagogue and educator

- Hrant Nazariants (Հրանտ Նազարեանց, 8 January 1880 – 25 January 1962), Armenian poet and writer

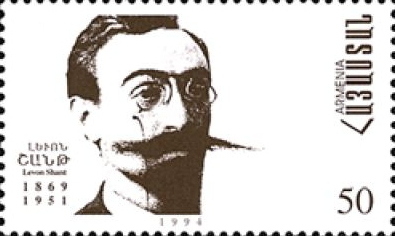

- Levon Shant (Լեւոն Շանթ; born Levon Nahashbedian, then changed to Levon Seghposian;Üsküdar, 6 April 1869 – 29 November 1951, Beirut), Armenian poet, writer, and playwright

- Sirvart Kalpakyan Karamanuk (Սիրվարդ Գալբագեան Գարամանուկ – Sirvard Galbagian Garamanuk; 1 December 1912 – 20 October 2008), Armenian composer, pianist, and teacher

- Shahan Berberian (Շահան Ռ. Պէրպէրեան – Shahan R. Perperian; 1 January 1891 – 9 October 1956); Armenian philosopher, composer, and pedagogue

- Srbuhi Kalfayan (Սրբուհի Մայրապետ Նշան Գալֆաեան – Srbuhi Galfaian, 17 February 1822 in Kartal, Constantinople – 4 July 1889, Hasköy, Constantinople), Armenian Apostolic nun and philanthropist

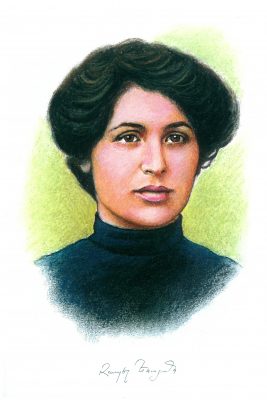

- Zapel Yesaian (Զապէլ Եսայեան; West Armenian Zabel, 4 February 1878 – 1943), Armenian poet,

Zapel Yesaian (painter: Khoren Hakobyan) writer, and teacher. She was the only woman on the list for the mass arrest of Armenian notables in Constantinople in 1915, but managed to escape abroad in time. There followed an eventful life in exile and in 1926 her first trip to Soviet Armenia. In 1934 she moved there and was caught up by the fate she had escaped in 1915: in the course of a second eliticide, a Soviet court condemned her as an ‘enemy of the people’ in 1937, after she had previously stood up for her persecuted male colleagues Yeghishe Charents and Axel Bakunts; her death sentence was commuted to ten years of banishment in 1939. It is unclear whether Zapel Yesaian was murdered while still in prison in Baku, or in Siberia. She disappeared forever, like many of her Armenian colleagues before her.

History

Üsküdar was founded in the 7th century B.C. by ancient Greek colonists from Megara as Chrysopolis, a few decades before Byzantium was founded on the opposite shore. The city was used as a harbor and shipyard and was an important staging post in the wars between the Greeks and Persians. In 410 B.C. Chrysopolis was taken by the Athenian general Alcibiades, and the Athenians used it thenceforth to charge a toll on ships coming from and going to the Black Sea. Long overshadowed by its neighbor Chalcedon during the Hellenistic and Roman period, it maintained its identity and increased its prosperity until it surpassed Chalcedon. Due to its less favorable location with respect to the currents of the Bosporus, however, it never surpassed Byzantium.

In A.D. 324, the final battle between Constantine I, Emperor of the West, and Licinius I, Emperor of the East, in which Constantine defeated Licinius, took place at Chrysopolis. When Constantine made Byzantium his capital, Chrysopolis, together with Chalcedon, became suburbs. Chrysopolis remained important throughout the Byzantine period because all trade routes to Asia started there, and all Byzantine army units headed to Asia mustered there. During the brief usurpation of the Armenian general Artabasdos, his eldest son, Niketas, was defeated with his forces at Chrysopolis by the army of Constantine V, before Artabasdos was finally deposed by the legitimate emperor Constantine and blinded. For this reason, and because of its location across from Constantinople, it was a natural target for anyone aiming at the capital. Also, in the 8th century A.D. it was taken by a small band of Arabs, who caused considerable destruction and panic in Constantinople, before withdrawing. In 988, a rebellion that nearly toppled Basil II began in Chrysopolis, before he was able to crush with the aid of Russian mercenaries.

In the 12th century, the city changed its name to Skutarion, the name deriving from the Emperor’s Skutarion Palace nearby. In 1338 the Ottoman leader Orhan Gazi took Skutarion, giving the Ottomans a base within sight of Constantinople for the first time.

In the Ottoman period Üsküdar was one of the three communities outside the city walls of Constantinople (along with Eyüp and Galata). The area was a major burial ground, and today many large cemeteries remain, including a number of Jewish and Christian cemeteries.

The neighborhood suffered during the ethnic-religious violence of the 6 September 1955, Istanbul pogrom (Grk.: Septembriana). Turkish rioters looted Greek and Armenian Christian shops and many Greeks and Armenians subsequently fled the country.

Destruction

1912-1918

“Diocese of Chalcedon

On the outbreak of the European War [First World War], persecution and oppression became more and more intense. Every means for suppressing the intellectual and economic activity of this Greek element was resorted to and the despoiling of Greek property was carried to the utmost limits.

Many million pounds worth of goods were, so to say, requisitioned or taken away by threats from the Christian populations of Cadikeuy [Kadıköy; Chalcedon], Scutari, Cartal [Kartal], Doudja [Düzce?], Bakalkeuy [Bakalköy], Tchengelkeuy [Çengilköy], Pasha-Baktche [Paşabahçe], Beicos [Beykoz] Heraclea and the rest of the Diocese. No less than fifteen letters were addressed to the shepherds of Neohori from the Turks, ordering them to abandon their flocks and leave the country, threatening to put them to death to the last man if they did not obey. A shepherd named Aristidis refused to comply with the order, and all his fingers were cut off. Terror-stricken, many shepherds conducted their flocks into other districts, where they were equally threatened and returned to the places they started from. It was only when the Christians decided to defend themselves that the menacing attitude of the neighbouring Turks was put an end to, and the Christian element of Guelze [Gülze], Chile [Çile], Candri, and Tache-Keupru [Taşköprü], enjoyed comparative tranquility. And although Talaat, then Minister of the Interior, endeavored to incite the authorities of various places to restart the persecution, they refused on the ground that the Christians knew too well how to defend themselves.

The mobilization of the Christians ruined many Communities of the Diocese, and those employed at Angora for the construction of roads died of hunger, having been deprived by their officers of their rations, while any complaint against them on the part of the Christian soldiers only brought much punishment and death. Further measures for exterminating the Christians were practised.

When all these methods of oppression were exhausted, the Government started deporting the members of a given number of communities. (…)”[2]