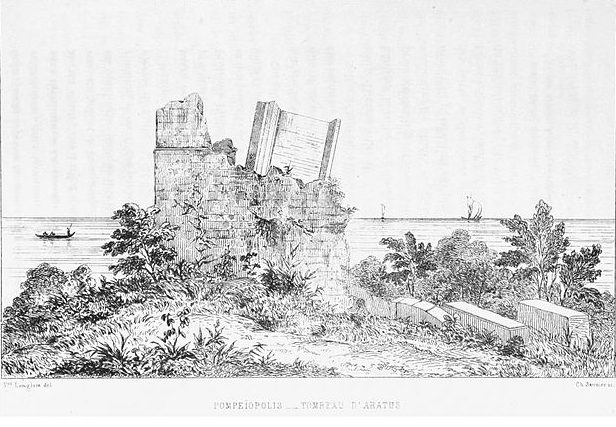

“Mersina is the port of Tarsous; this small city was called Zephirium in ancient times. There are many ancient remains in the area: sculptures, pottery and medals.”[1]

Toponym

The city’s name derives from the aromatic plant genus Myrsine (Grk.: Μυρσίνη – Mirsini) in the family Primulaceae, a myrtle that grows in abundance in the area. In antiquity, during the Ancient Greek period, the city bore the name Zephyrion (Grk.: Ζεφύριον). Zephyrion, whose name was Latinized to Zephyrium, was renamed as Hadrianopolis in honor of the Roman emperor Hadrian.

Population

According to the Armenian Patriarchate in Constantinople, the pre-war Armenian population of sancak Mersin was 6,987. They lived in three localities – in Mersin (2,300), Tarsus (Grk.: Tarson, Armenian: Darson; over 3,000 Armenians in 1914) Kozoluk (290) and several villages near Mersin – and maintained four churches. According to the Armenian Patriarchate in Constantinople, the pre-war Armenian population of the sancak Mersin was 6,987. They lived in three localities and maintained four churches[2], of these two churches in the town of Mersin. In the governmental seat of the sancak, Mersin, lived also Syrian and Circassian immigrants as well as Greeks from Cyprus.[3]

History

This coast has been inhabited since the 9th millennium B.C. In subsequent centuries, the city became a part of many states and civilizations including the Hittites, Assyrians, Urartians, Persians, Greeks, Armenians, Seleucids and Lagids. Apart from Mersina’s natural harbor and strategic position along the trade routes of southern Anatolia, the city profited from trade in molybdenum (white lead) from the neighbouring mines of Coreyra. Ancient sources attributed the best molybdenum to the city, which also minted its own coins.

The area later became a part of the Roman province of Cilicia, which had its capital at Tarsus, while nearby Mersin was the major port.

After the death of the emperor Theodosios I in 395 and the subsequent permanent division of the Roman Empire, Mersin fell into what became the Byzantine Empire.

The city was an episcopal see under the Patriarchate of Antioch. Le Quien names four bishops of Zephyrium: Aerius, present at the First Council of Constantinople in 381; Zenobius, a Nestorian, the writer of a letter protesting the removal of Bishop Meletius of Mopsuestia by Patriarch John of Antioch (429–441); Hypatius, present at the Council of Chalcedon in 451; and Peter, at the Council in Trullo in 692.

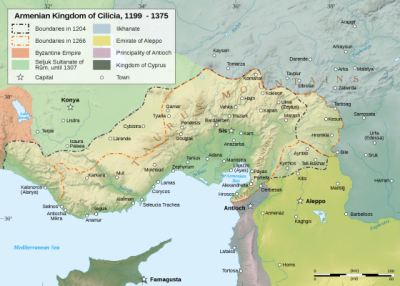

Cilicia was conquered by the Arabs in the early 7th century, by which time it apparently was a deserted site. After them came the Egyptian Tulunids, the Byzantines between 965 and the 12th century, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia, Mamluks, Anatolian beyliks, and finally the city was conquered by the Ottomans from the Ramadanid Principality in 1473 and formally annexed by Selim I in 1517.

The Latin Catholic Church of Saint Anthony (1853), the Greek Orthodox Church of Saint Michael and Gabriel and the “Old Mosque” (Eski Cami, 1870) are among the most important buildings from the Ottoman period. The Maronite church building was restored and converted into a mosque in different periods.

To the west of the city are the remains of a Hittite fortress from the 14th or 13th century B.C. Mersin is associated in history with the names of St. Paul of Tarsus and with the fact that Mark Antony gave the lands between Alanya and Mersin to Cleopatra as a wedding gift.

Today, neighborhoods such as Frenk Mahallesi (European Quarter), Giritli Mahallesi (Cretan Quarter) and Hıristiyan Köyü Mahallesi (Christian Village Quarter) are reminders of the former religious-cultural diversity in the city.

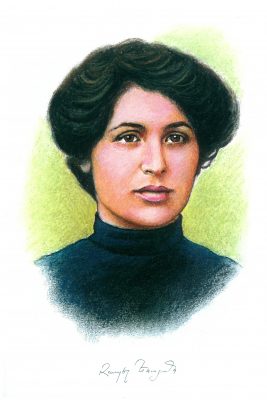

Zapel Yesaian: The Children of Mersin: After the 1909 Massacres

The Armenian writer travelled from her native Constantinopel to Cilicia via Smyrna as a member of a commission of inquiry, sent by the Armenian Apostolic Patriarchate of Constantinople in order to investigate the humanitarian situation of the devastated Armenian communities in Cilicia.

“By the time we reached Mersin, I was prepared to see a picture of the greatest desolation. Tormented by the memory of the orphans we had seen in Smyrna, my imagination was expecting similar horrors on a frightfully larger scale. But what I saw was past all imaging. I find it hard to give an idea of the whole. With their ordinary, everyday meanings, words are incapable of expressing the terrible, indescribable scene that my eyes beheld.

In the days when those who escaped the flames fell victims to the bullets, when frenzied, panicked people, in a desperate effort to save their lives, trampled the weak and vulnerable underfoot, most children had been separated from their parents and scattered right and left. The first delegation dispatched by the Patriarchate had rounded them up a few at a time and sent them on to shelters set up in Mersin’s Armenian school and church, so that, far from the scene of the catastrophe, the poor

children might forget those horrible days, if only partially, and so that they would not have to tread the ground on which their parents’ blood had been spilled. Many people described the children’s arrival for us. They were nearly naked or dressed in rags often stained with the traces of their mothers’ blood. Their heads were bare; their eyes wandered aimlessly. They arrived in Mersin in groups, and the smell of the dirt and sweat of their bodies floated for a long time in the dust clouds raised by their bare feet.

When they had been assembled in the church, they were still terrified and neither spoke nor cried. The fear haunting those little children had been so great that, when they saw anyone at all, they shivered like someone in the grip of a fever. In the imagination of those tender innocents, grown-up all looked alike. They saw a criminal in every adult male, were deluded by terrifying resemblances, imagined ghastly scenes and wanted to flee – panicked, horror-stricken, stupefied, and shocked. They young minds were deranged, because for days on end they had seen criminals brandishing knives or rifles, eyes burning with a lust for evil, mouths contorted by curses and threats. Blood had poured down like rain around those children, and for hours the pupils of their eyes had been wide with the terror inspired by the flames.

Left to themselves, the boys and girls would calm down. Sometimes they conversed, although their conversation were interrupted by lang silences. Sometimes they were all overcome by the same pain; then they sobbed, refusing to be comforted, abandoned to, and nearly annihilated by, the violence of their grief. Because their suffering exceeded their childish powers of endurance, some of them, eyes still full of tears and chests swollen with sobbing, laid their heads down on their desks and slept for hours.

Others, suddenly feeling the need for tenderness and a family’s love, fraternized with their companions in misery. (…)

These children were aware that they filled me with horror. Their psychological makeup disturbed me, and I could not look them in the eye. With a sharp, irrepressible pang, I saw that there were indelible nightmares there, and that childhood’s smile, childhood’s bright, pure light had gone out in their eyes. On their dark-skinned, somber, gloomy faces, you could sometimes read, as in an open book, all the terror of hours that defied description; but, at other times, everything clouded over, and then the children were impenetrable. And that was even more unsettling.”

Excerpted from: Yessayan, Zabel; In the Ruins: The 1909 Massacres of Armenians in Adana, Turkey. Translation by G.M. Goshgarian. Ed. By Judith Saryan, Daniola Jebejian Terpanjian and Joy Renjilian-Burgy. Boston, MA: Armenian International Women’s Association (AIWA), 2016, pp. 24-26

Destruction

As a result of the 1909 massacres, the Christian population of sancak of Mersin had already declined. During World War I, both the Greek Orthodox population and the Armenian population were affected by the elitism of their notables and by deportations, as mentioned in a documentation of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople:

“Tarsos and Adana (dependent on the Patriarchate of Antioch) also suffered from deportations. At the beginning of the European war the Christian [Greek Orthodox] population of Mersina was deported to Adana and Tarsus for military reasons, as if the military reasons did not apply equally to all the population of a town in general. At the same time the inhabitants of the neighbouring agglomerations were also deported. About seventy notables of Tarsus were exiled to the district of Aleppo in April, 1918.”[4]

Raymond Kévorkian summarized the events in the city and the sancak of Mersin:

“While the vali of Adana showed a degree of moderation that benefited the local Armenian population, the same did not hold for Mersin (…).

In late April, six ‘suspects’ fell victim to a first wave of arrests. They were sent off to Adana, where they were imprisoned on the former French lycée together with 30 men from the city. The American consul Edward Nathan also notes the deportation of a few dozen families from Mersin and Taurus around 18 May 1915. 600 families were gradually deported from Mersin with the result that only around 30 craftsmen and their families were still living there by the fall, including the only Armenian in the town to have converted, Khoren Sarafian. A second wave of deportations, organized in February 1916 after the British had shelled Mersin put a definite end to the Armenian presence in the city.”[5]

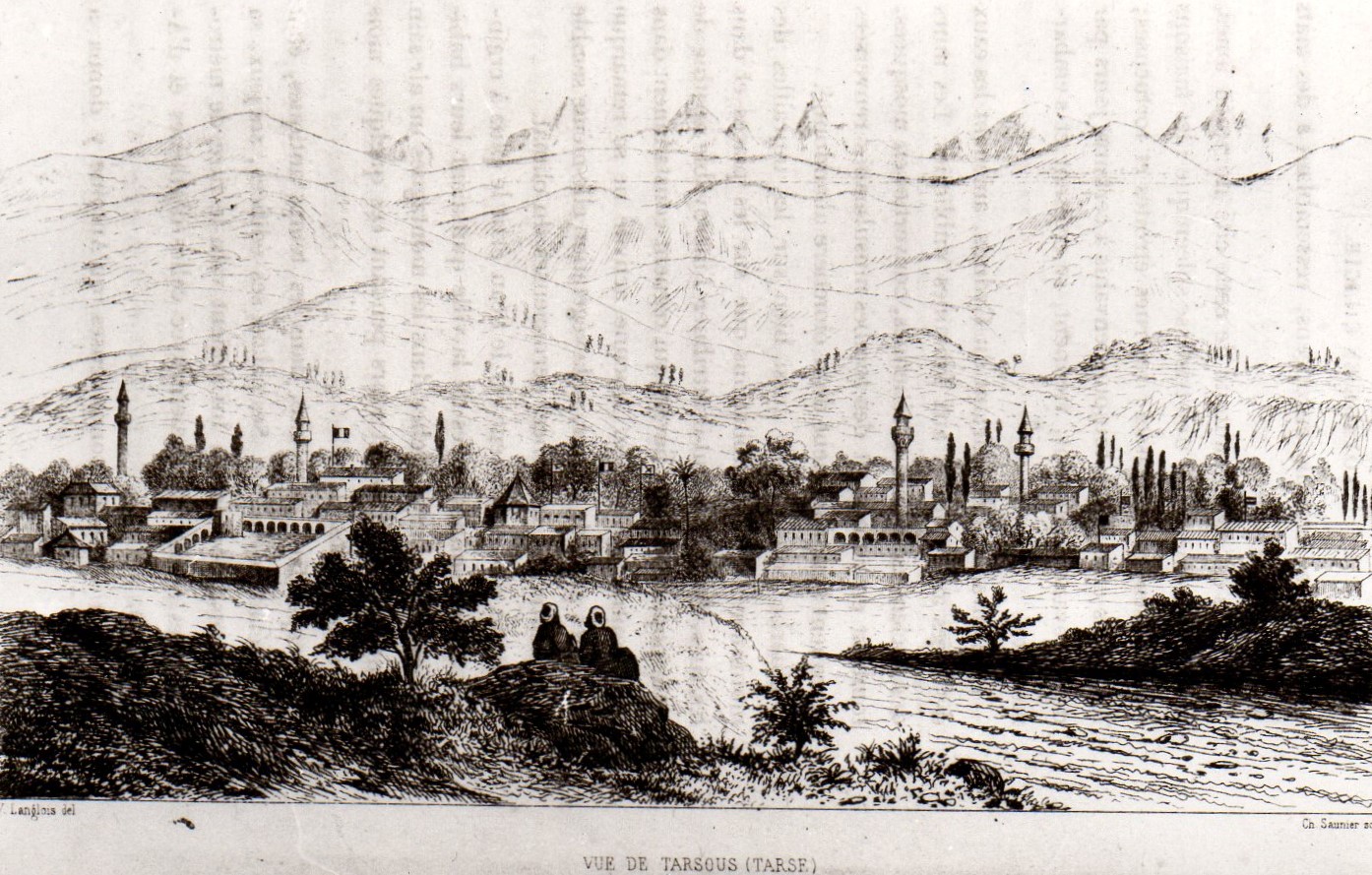

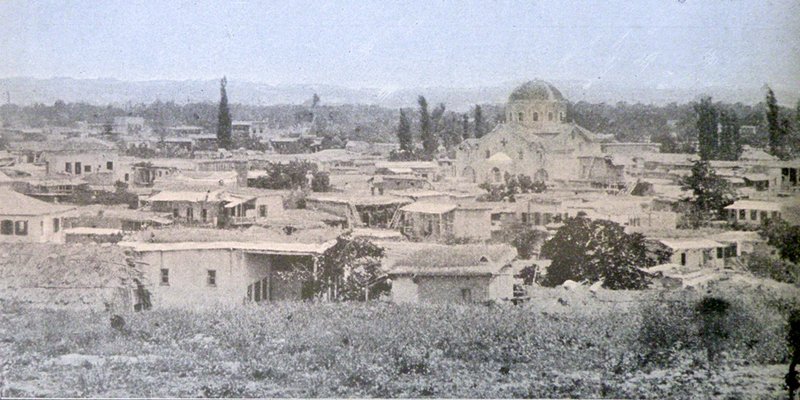

City of Tarsus / Tarsos / Tarson / Darson

Toponym

Under the Seleucids, the city was named Antioch on the Kydnos in 171 B.C., and under Roman influence (from 66 B.C.) it was renamed Juliopolis (after 47 BC), in memory of Gaius Iulius Caesar, to whom it was loyal during the Civil War.

History

The former port city of Tarsus on the Gulf of İskenderun, which maintained trade relations with Phoenicia and Egypt, was located about two to three kilometers from the Mediterranean Sea and was accessible via the navigable river Kydnos (today’s name Berdan Çayı). Today, the port is silted up and the city is located about 16 km from the sea.

The oldest settlement layer dates back to the 4th millennium B.C. If the equation Tarša/Tarsus (Šuppiluliuma-Sunaššuraš Treaty) is correct, the city belonged to the principality of Kizzuwatna for a time. Under the Hittites it developed into an important center of Cilicia. Around 1200 B.C. Tarsus was destroyed by the Sea Peoples, then at least partially settled by Greeks, as numerous Mycenaean finds show. Tarsus is first clearly attested in writing in Assyrian texts, which describe the conquest by Sanherib. Shortly thereafter, Tarsus became the capital of an Assyrian province.

After the Assyrian era, the city fell under the rule of Babylon, Iran and finally Alexander the Great.

Tarsus gained historical fame through the meeting of Cleopatra with Marcus Antonius in 41 B.C. Under the Sassanids, Tarsus was temporarily conquered in 259, then came under the influence of Palmyra and the Roman vassal Odaenathus. It was reconquered by Aurelian in a campaign against Zenobia and finally came under Byzantine sovereignty through the division of the empire. Emperor Julian was buried in Tarsus in 363. The Persians conquered the city in 614. The Arabs held Tarsus until 965, when Nikephoros II Phokas conquered it for Byzantium. It was the seat of the governor of Cilicia. After the Battle of Manzikert, Tarsus was part of the territory ruled by Abul Gharib. The Crusaders took it temporarily in 1097. Tarsus then became part of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. Finally, the city fell to the Mamluks in 1355, then to the Ottomans.

Notables

- Antipatros of Tarsos (* before 200 B.C. in Tarsos; † 129 B.C. in Athens), head of the Stoic school

- Athenodoros Kordylion (* in the first half ofthe 1st century B.C. in Tarsus), head of the library of Pergamon

- Athenodoros Kananites, teacher of Tiberius (1st century B.C.); born in the villageKana (Cana) near Tarsus, Athenodoros returned – as Strabon reports – as an old man from Rome to Tarsus and dedicated himself to the local politics in his

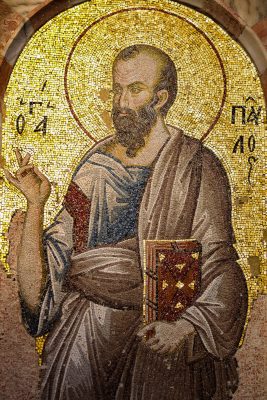

Apostle Paul (Mosaic in Chora Church, Istanbul; source: https://ecc-studienreisen.de/artikel/westtuerkei-die-missionsreisen-des-paulus-apostel-der-voelker) father city. His merits, which he had acquired by introducing a municipal order for this city, were still honored long after his death by a sacrificial service.

- Boniface of Tarsus, martyred in Tarsus 14 May 306

- Diodorus of Tarsus (born Antiochia – died before 394), bishop of Tarsus

- Julian of Tarsus, Christian martyr (born Cilicia, martyred 4th or 5th century)

- Theodore of Tarsus (Grk.: Θεόδωρος Ταρσοῦ; 602 – 19 September 690), 7th Archbishop of Canterbury

- Saint Nerses IV Pahlavuni (Shnorhali – ‘The Graceful’, (*1102 at Tzovk Castle, † 1173 in Tarsus), Armenian Apostolic Catholicos of Cilicia

Destruction

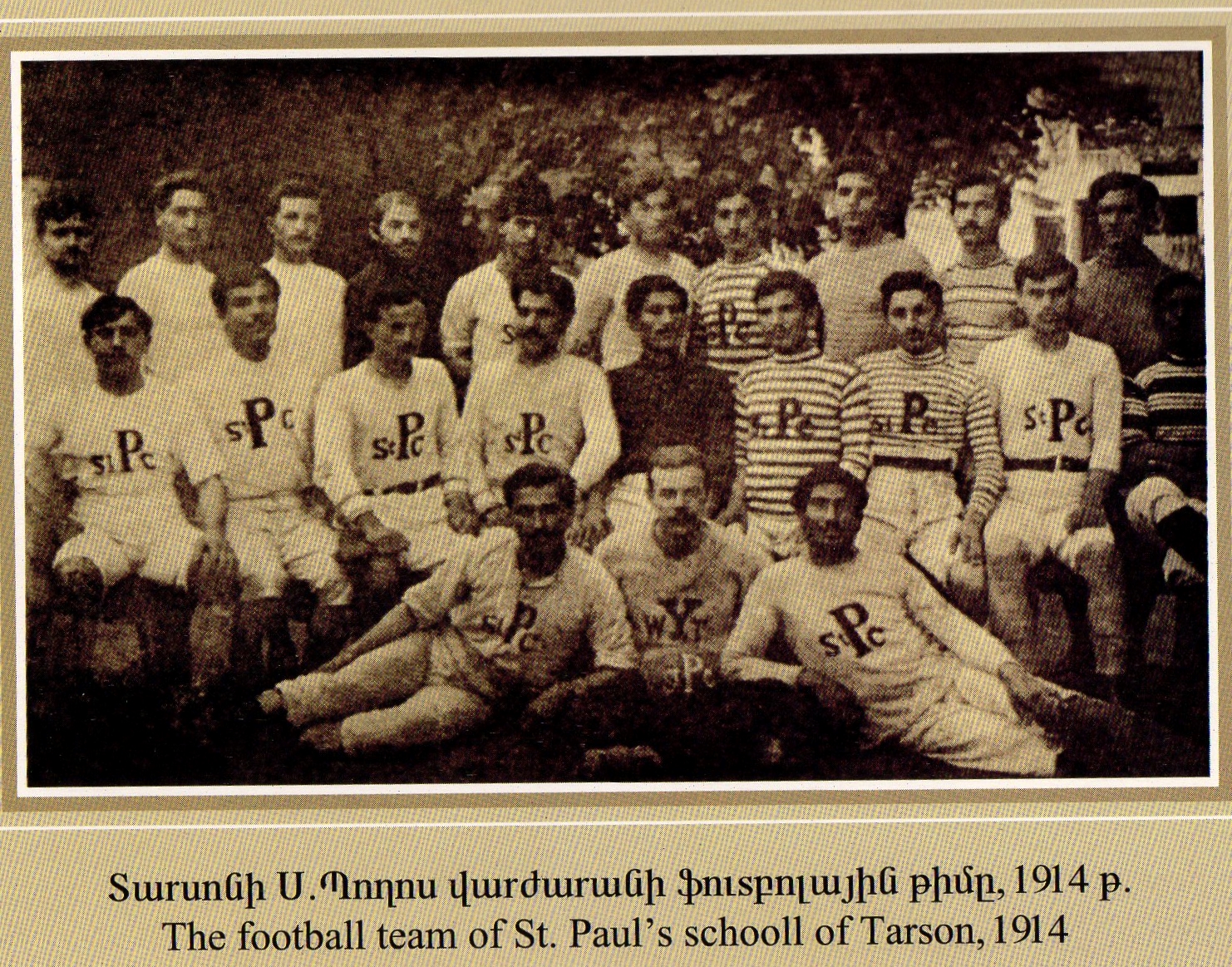

“Apart from a few dozen notables who were deported around 18 May, the Armenians of Tarsus were put on the road at the same time as those of Adana, with the further exception of a handful of craftsmen and employees working in state enterprises, as well as their families. The Shalvarjian brothers, who were millers, were also spared; all of them boasted of the great generosity that they showed both the intellectuals mentioned earlier and the deportees in the camp at the Gülek train station, through which all the convoys traveling by rail to Osmaniye had to pass.

In September 1915, the American consul was still hoping to save the last Armenians threatened with deportation, the ‘pupils’ of the Institute of St. Paul of Tarsus, whom the local authorities were seeking to lay hands on and deport using all means at their disposal.”[6]