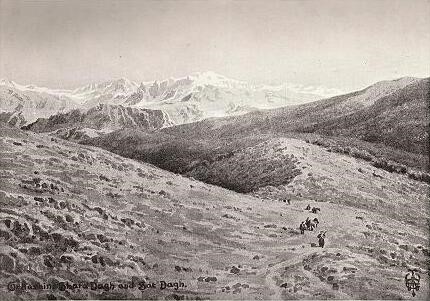

From the top of the ‘staircase’ pass immediately above Amadia. TThe toponym Dize derives from Kurdish ‘diz’ (‘fortress’).he mountain in the center is Ghara Dagh [Karadağ] on the southern side of Tkhuma. To the left is Galiashin, the dominant peak of Jilu: and Sat Dagh further off upon the right. The crags in the middle distance rise up out of the Zab Gorge. – Source: Wigram, W[illiam] A[inger]; Wigram, Edgar T.A.: The Cradle of Mankind: Life in Eastern Kurdistan. 2nd ed. London: Adam & Charles Black, (1922), http://www.aina.org/books/com/com.htm#c26

Toponym

Gavar is a high-level plain, as also its Kurdish name (gever or gevar – raised meadow) indicates. In the course of the Turkization of place names it was renamed 1936 in Yüksekova (‘plateau’). In Armenian, however, ‘gavar’ refers to an administrative unit (‘district’ or ‘province’). Persians adapted the homonymous Aramaic term Gavar (or ‘Gaur, Gwer, Gabr, Gawr’) to denote Zoroastrians in Mesopotamia. In the Islamic era the term was applied to all non-Muslim people of the Middle East (‘Giaour, Gavur, Kuffar’), meaning ‘infidel’.

The toponym Dize derives from Kurdish ‘diz’ (‘fortress’).

Population

Situated on the border with Iran, its location on the trade route between northwestern Iran and eastern Turkey made the region an important juncture for travelers and the location of several ethnic groups that were active in regional trade.

In the 1810s, the entire population of villages in the region of the Great or Upper Zab River were Assyrians (East Syriacs) until the genocide of 1914-1918. The kaza Gavar had around 1,497 families in the 1880s. In the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, there were around 30 villages in the kaza, which had an overall population of 15,000 before the First World War. Inhabitants lived off agriculture that mainly consisted of wheat, barley, cotton and tea.

Up until World War I, Gavar was the seat of a bishop of the Assyrian Church of the East (officially Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East). The district of Gavar served as the main travel stop for Assyrians traveling between the Hakkari tribal areas and the Urmia plains.

The once homonymous administrative center of the kaza Gavar is now the city of Yüksekova (since 1928: Dize).

The Debatable Land (Gawar, Tergawar, Mergawar)

“The plain [of Gavar] measures about sixteen miles by ten, and is in form an oval with pointed ends, the long axis running nearly north and south. It is absolutely treeless, save for a few poplars round the villages that are scattered over its face. Though but little of the plain is cultivated it is all magnificently fertile; for the black alluvial soil grows anything that will endure the long winter and deep snow natural at an elevation of six thousand feet; and the corn and melons of Gawar are famous throughout the land.

A considerable river, the Nihila or Nile, wanders down the centre and is joined by several others from the high mountains at the sides. This river on leaving the plain flows northward through a deep and fine gorge to join the Albak; and their united streams constitute the Zab.

Being thus a dead level, Gawar looks as easy a place to cross as well can be. We see our destination before us perhaps twelve miles away, and nothing seems to be necessary but to make a bee-line for it. In reality few things are more difficult than crossing this or a similar plain, unless you know the way or have a guide who knows it. The river is bordered with wide swamps; and such fords as exist upon it (and they are not many) can only be approached from certain directions: while the stranger is constantly liable to stumble (like the luckless Duke of Monmouth) on rhines or irrigating channels; the muddy bottoms of which are unfordable for animals, except at certain points known only to the villagers around.

A fertile level like this should swarm with villages and carry a large population; but of the villages that once were here (almost all of which were Nestorian Christian) many are now absolutely deserted, and others have become Kurdish and so do little work in the world. This has been brought to pass, not by the villagers abandoning their Christianity – for that is so rare a thing as to be almost unknown – but by what foreign residents characterize as ‘the hermit crab Act’.

This process is as follows. Given a village of Christians; with Kurds in the neighborhood: a party of Kurds (men who have probably made their own village too hot to hold these, or who have quarreled with their chief) come and settle at free quarters in the place as ‘guests’. The villagers cannot turn them out; for they are armed, and they are not; and stingless worker bees can hardly expel sting-bearing drones. If they appeal to the Government for redress, the official is bribed by the intruders to do nothing (the bakhshish being extorted from the villagers); and the answer is made ‘have not these Mussulmans the right to reside where they like?’ If any man does head an attempt to evict them, a ‘dead set’ is made at him till he is worried into leaving the village and his land; and this the Kurds immediately appropriate, forcing the other villagers to work it for them without pay. The village mill is usually one of the first places taken, and a liberal percentage of the corn goes as a fee for the grinding of it. Meantime, what the presence of these fellows means for the ‘rayats!’ in the way of petty oppression, and what the consequences are to the girls of the village, anyone who has some knowledge of human nature can be left to guess for himself.

If the plan prospers other Kurds join; and the leader of the gang presently builds him a small hold, or kala (again with the forced labor of the villagers), and at length the bulk of the Christians are worried out of the country. Only a few are kept, as serfs, to till for their new masters the land that they and their fathers once owned; and what was a Christian village has become Kurd.

If ever one sees a Kurdish village which has good fields, and signs of good cultivation, one can be sure that it was originally Christian, and that it has gone through this process.”

Source: Wigram, W[illiam] A[inger]; Wigram, Edgar T.A.: The Cradle of Mankind: Life in Eastern Kurdistan. 2nd ed. London: Adam & Charles Black, (1922), http://www.aina.org/books/com/com.htm#c26 (Last retrieved February 24, 2019)

The massacre of Gavar Syriacs at the Kala of Ismael Agha (April 1915)

The Annual Report for 1915 of the Medical Department at Urmia, published in the British Blue Book (1916) contains two mentions of the massacre of East Syriac  forced labourers from the Gavar plain near the fort (‘kala’, ‘kale’) of a certain Ismail Ağa. Both mentions differ slightly in terms of the number of victims and the ethnic identity of the perpetrators:

forced labourers from the Gavar plain near the fort (‘kala’, ‘kale’) of a certain Ismail Ağa. Both mentions differ slightly in terms of the number of victims and the ethnic identity of the perpetrators:

Extracts from the Annual Report (for the year 1915) presented by the Medical Department at Urmia to the Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A.

(…)

“The most diabolically cold-blooded of all the massacres was the one committed above the village of Ismael Agha’s Kala, when some sixty Syrians of Gawar were butchered by the Kurds at the instigation of the Turks. These Christians had been used by the Turks to pack telegraph wire from over the border, and while they were in the city of Urmia they were kept in close confinement, without food or drink. On their return, as they reached the valleys between Urmia and Baradost plains, they were stabbed to death, as it was supposed, but there again, as in two former massacres, a few wounded, bloody victims succeeded in making their way to our hospital.”

The testimony of the survivors of the massacre at Ismael Agha’s Kala is confirmed by the following extract from a letter, dated 8th November, 1915, from the Rev. E.T. Allen of Urmia:

“(…) Yesterday I went to the Kala of Ismael Agha and from there to Kasha, and some men went with me up the road to the place where the Gawar men were murdered by the Turks. It was a gruesome sight – perhaps the worst I have seen at all. There were seventy-one or two bodies; we could not tell exactly, because of the conditions. It is about six months since the murder. Some were in fairly good condition – dried, like a mummy. Others were torn to pieces by the wild animals. Some had been daggered in several places, as was evident from the cuts in the skin. The majority of them had been shot. The ground about was littered with empty cartridge-cases. It was a long way off from the Kala, and half-an-hour’s walk from the main road into the most rugged gorge I have seen for some time. I suppose the Turks thought no word could get out from there – a secret, solitary, rocky gorge. How those three wounded men succeeded in getting out and reaching the city is more of a marvel than I thought it was at the time. The record of massacre burials now stands as follows:

At Tcharbash, forty in one grave, among them a bishop. At Gulpashan, fifty-one in one grave, among them the most innocent persons in the country; and now, above the Kala of Ismael Agha, seventy in one grave, among them leading merchants of Gawar.

These one hundred and sixty-one persons, buried by me, came to their death in the most cruel manner possible, at the hands of regular Turkish troops in company with Kurds under their command.“[1]