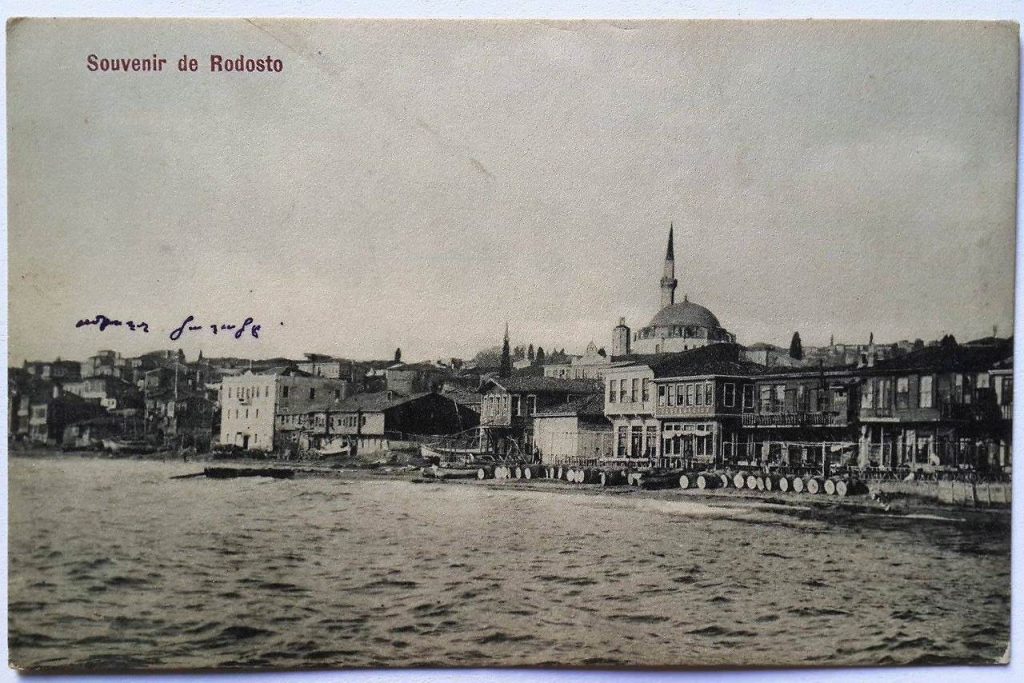

Toponym

Situated in Eastern Thrace (Propontis) on the Sea of Marmara, the port city and administrative seat of the Ottoman sancak of Tekfürtaği (Tekfürdağı) was called Bisanthe or Bysanthe (Βισάνθη/Βυσάνθη), and also Raidestos (Ῥαιδεστός) in classical antiquity. The latter name was used until the Byzantine era, transformed to Rodosçuk after it fell to the Ottomans in the 14th century (in western languages usually rendered as Rodosto). After the 18th century it was called Tekfür Dağı (‘Tekfür Mountain’), based on the Turkish word tekfur (Ottoman Turkish: تكور, romanized: tekvur), which was a title used in the late Seljuk and early Ottoman periods to refer to independent or semi-independent minor Christian rulers or local Byzantine governors in Asia Minor and Thrace. It has been suggested that ‘tekfur’ (tekfür) derives from the Byzantine imperial name Nikephoros, via Arabic Nikfor. It is sometimes also said that it derives from the Armenian ‘tagavor’ (թագավոր – ‘king’; Western Armenian pronunciation ‘takavor’).

Over time, the name mutated into the Turkish Tekirdağ. The historical name Raidestos was continuously used until today in Greek Orthodox ecclesiastical context (e.g. Bishop of Raidestos, Metropolitanate of Heraclia and Raidestos, 18th-19th centuries).

Administration

Under Ottoman rule the city of Rodosto and its environs was successively a part of the Rumelia Eyalet, the the Province of the Kapudan Pasha (also Eyalet of the Archipelago), the Silistra Eyalet, and Edirne Vilayet. Previously called the sancak of Vize (Grk.: Bizye), which was separated from the Eyalet Silistra in 1846 and assigned to the province of Edirne / Adrianople, the town of Vize itself was detached in 1879 and came under the Sancak of Kırk Kilise. The administrative seat of the previous sancak of Vize was moved to Rodosto (Tekfürtagi) after 1849, and the sancak was accordingly renamed Tekfürtaği. Towards the end of the 19th century, the sancak of Tekfürtagi comprised a territory of 4,600 square kilometers.(1) In 1912, the sancak of Tekfürtagi encompassed the four kazas of Tekfürtaği proper, Malkara, Çorlu (Grk.: Tyroloi), and Hayrabolu (Grk.: Harioupolis).

Population

According to Ottoman statistics of 1910, the sancak of Rodosto had an overall population of 144,300; of these, 63,500 were Turks, 56,000 Greeks (Greek Orthodox Christians), 3,000 Bulgarians and 21,800 “others”.[2]

Ecclesiastically, the sancak of Rodosto belonged to the Diocese of Herakleia. It consisted of 74,036 Greek Orthodox Christians in 82 parishes.[3]

Armenian population

On the eve of the First World War, there lived 22,368 Armenians in nine localities of the sancak of Rodosto and in Eastern Thrace. They maintained seven churches and monasteries and nine schools with an enrolment of 1,873 pupils.[4] For the sancak of Rodosto alone, Raymond Kévorkian mentions an overall Armenian population of “roughly 17,000” in 1914.[5]

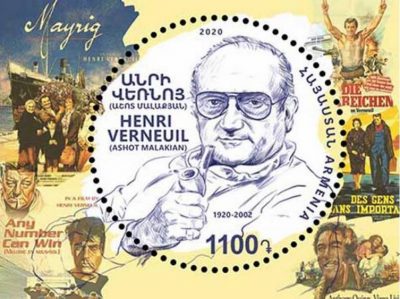

Notables

Henri Verneuil (born Ashot Malakian, 15 October 1920, Rodosto – 11 January 2002; Bagnolet, France); French-Armenian playwright and filmmaker. Born to Armenian genocide survivors, in 1924 Verneuil and his family fled to Marseille in France, to escape persecution after the Ottoman genocide. He later recounted his childhood experience in the novel Mayrig (‘Little Mother’), which he dedicated to his mother and made into a 1991 film with the same name, which was followed by a sequel, 588 Rue Paradis, the following year.

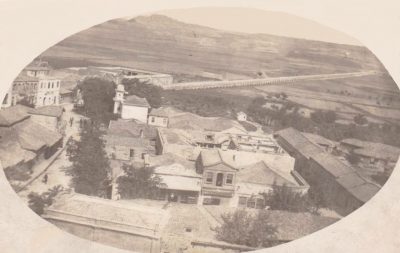

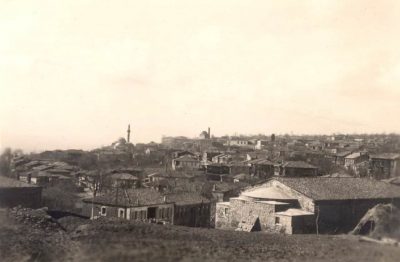

Town of Rodosto

Population

In 1905, Rodosto had a population of about 35,000; of whom half were Greeks, who were exchanged with Muslims living in Greece under the 1923 agreement for forcible Exchange of Greek Orthodox and Muslim Populations between the two countries.

History

The history of the city of Tekirdağ dates back to around 4000 B.C. In Xenophon‘s Anabasis it is mentioned to be a part of the kingdom of the Thracian king Seuthes. It is also mentioned as Bisanthe by Herodotus (VII, 137).

The city was a Samian colony. Its restoration with an additional fortress wall by Justinian I in the 6th century A.D. after the barbarian invasions is chronicled by Procopius of Caesarea. The Bulgarians conquered and destroyed the city in 813 under Khan Krum and again in 1206, after the Battle of Rodosto, under Tsar Kaloyan, but each time it was rebuilt shortly after and continued to appear as a place of considerable note in later Byzantine history. It was also ruled by the Venetians between 1204 and 1235.

Destruction

In late 1912, after the defeat at the Battle of Lüleburgaz (28 October – 2 November 1912) the retreating Ottoman army set fires on several parts of the town of Rodosto and massacred many Christians.[6] Even children were thrown to the flames.[7]

A report dated 10 July 1913 mentions that in Rodosto, twenty-three Greeks and eighteen Armenians were slained; that the neighboring village Kalyvia, consisting of eight hundred Greek families, was burned in its entirety, its inhabitants, including women and children, being butchered.[8]

As in the case of the Greek Orthodox Eastern Thracians (see below), the Armenian population of Eastern Thrace had already been victims of massacres and deportations before the outbreak of the First World War. “(…) the deportations were preceded by a number of alarming events. We must first recall the massacres perpetrated from 1 to 3 July [1914] by soldiers in Rodosto, which the Istanbul press quickly painted as a revolt that the army had had to ‘put down’. We cannot ignore the fire in the Armenian quarter that broke out on 26 August 1914 in the night of the general mobilization – it was, to say the least, of suspicious origin. Nor can we ignore the direct threats hanging over the heads of the Armenian population in the same period, which had compelled the interior minister [Mehmet Talat] to come to the port in person, accompanied by the patriarchal vicat, Perhjian, to reduce the tensions. According to a survivor, most of the conscripts from Rodosto were assigned to the region’s labor battalions from fall 1914 on; very few managed to avoid them. Yet, the first arrests, which targeted the city’s notables, were not made until Monday, 20 September. Officially, it was a question of ‘punishing’ people who were said to have ‘facilitated the Bulgarians’ entry into Tekirdağ’ during the Balkan war. The day after they were arrested, these men and their families were put aboard trains bound for Anatolia. On Wednesday, 22 September, a second wave of arrests took place, targeting once again entrepreneurs such as the Keremian Brothers, Krikor Shushanian, the Jamjian brothers, Hovagim Karanfilian, Hovhannes Papazian, or the lawyer Bedros. All were immediately put on the road. Thereafter, the deportations took a more systematic form. They went on until 31 October and affected 10,000 people, who followed the Istanbul-Konya-Bozanti [Pozantı]-Aleppo route and ended up in the Syrian Desert. By 10 November, 3,000 more people had been expedited; only the families of a few chosen soldiers were spared. On 20 February 1916, a final group of 120 was sent to Ismit [Izmit] by ship, where it was then sent on its way to Syria.

(…) According to statistics published by the Armenian Patriarchate, approximately 3,500 Armenians from Rodosto survived the deportations.”[9]

Greek-Orthodox Diocese of Herakleia (Marmara Ereğlisi)

“The diocese of Herakleia, consisting of a Christian population of 74,036 and divided into eighty-two Communities, was entirely destroyed owing to the methods of extermination adopted by the Young Turks.

Deportations, massacres, islamizing, requisitioning of property, arbitrary impositions, raping, plundering, and desecration of churches, such were in a word, the expedients to which the Young Turks had recourse, assisted by officials of all grades, and several notable Turks, including the ex-deputy Rodosto Adil Bey and his grecophone son Touad Bey, members of the Administrative Council of Rodosto.

The rigorous application of this program dealt a mortal blow to the once flourishing economic and educational life of the Greek population of this diocese.

Persecutions in 1913-1914

(a) Rodosto Region.

- RODOSTO. — This town witnessed some truly tragic scenes. Half its Greek population expatriated owing to the oppression and the rigorous boycott inflicted on them. This was the case with nearly the whole of Thrace. In December, 1913, policemen went through the Turkish, Jewish and Armenian quarters at the order of the Government, commanding that all commercial intercourse with the Greeks should cease. Besides this meeting took place in the Turkish quarter, at which it was decided that all Moslem proprietors who had Greek tenants should return the rent received from them and cancel the contracts.

Such were the impediments and restrictions imposed upon the trade that in a very short time out of 250 only twenty shops remained, the doors of which were guarded by Turks posted there to survey the application of the boycott. Besides this the Government requisitioned the schools and all buildings and property belonging to the Community.

- PANIDON. — Attacked in July, 1913, by the neighbouring Turks, this village was plundered and again attacked in August, 1914. Its inhabitants took refuge in Koumvas intending to return, but on the 13th of August of the same year, the Government sent steam ships and transported the Greek population to Greece.

- KOUMVAS. — Overrun by Turkish immigrants, oppressed and threatened not only by the Turks but by the Government officials as well, the inhabitants were obliged to expatriate.

- NAUP-KEUY [Naup-Köy?]. — The following reasons obliged the inhabitants of this village to depart: They were forced to subscribe for the fleet. Compelled to work on road making. Their lives were threatened, and lastly, the Chief of the Gendarmerie, Sukry [Şükri] Bey, finally gave them the friendly advice to go.

- SKOLARION. — On Easter Sunday, the Administrator of Rodosto and the Chief of the Gendarmerie, Sukry [Şükri] Bey, arrived here, subjected the inhabitants to forced labour, and subscriptions for the Turkish fleet.

Later on, the village was attacked by the Turks of the immediate vicinity, and after oppressing the Christians in divers manners, they took away their sheep, to the amount of 35,000 head. In vain did the Christians protest and appeal to the Administrator for redress. They were obliged finally to evacuate the village.

- SIMITLI. — Attacked on every side, taxed heavily, the inhabitants of this village sought refuge in that of Skolarion, on the 8th August. Ahmed Effendi, Mudir of Koumvas, was especially instrumental in their deportation. Dimitri Kalasticakis, Fotini Hadji Dimitriou, and Nicolaos Kalasticakis, were murdered. Panayiotis Kamparis and Yioanis Kizlaris were seriously wounded.

- CHANKANDJI [Çankancı].— Lieutenant Chukri [Şükri] informed the villagers of his inability to protect them against the hostility of the Turks of the adjacent villages, and asked that they should evacuate the place in twenty-four hours, using pressure in order to make them sell their cattle and goods and chattels. The inhabitants removed to Greece after they had signed a document to the effect that they departed at their own free will.

- SELDJIKEUY [Selciköy] . — The greater part of the village was burnt down in July, 1913, by the re-occupation of soldiers of Thrace and the neighbouring Turks. Two hundred and ninety Christian families were exposed to the danger of being massacred. In April, 1914, a government official ordered the village to be evacuated in twenty-four hours. After many entreaties, accompanied by a bribe of Ltq.50, he promised to extend the limit to three days. But on the same day, masses of armed Turks forced the Christians to evacuate the place and resort to Greece.

- KIOSELEZ. — The inhabitants were deported, via Rodosto, to Greece.

(…)

(b) Deportations during the European War.

(a) Ouzoun Keupru [Uzunköprü] Region.

- OUZOUN KEUPRU [Uzunköprü].— The remaining inhabitants of this village were deported gradually. The first proscription took place on the 20th September, at midnight. Twenty-nine Christian families were driven out of their homes, put on cars held ready by the authorities, and arrived after a three days’ march at Malgara, where they were thrown into the houses previously occupied by the deported Armenians. The second batch was dispatched under the same conditions on the 8th October, 1915, at midnight. This company comprised fifty families, who were also sent to Malgara. The third and last deportation took place at midnight on the 18th October, 1915. In the meantime, about thirty families took shelter in Constantinople, Adrianople, Bulgaria, and elsewhere. Their furniture, corn, and other objects were confiscated. The schools and Church were requisitioned.

- DERVINAKI.— The Mudir of Tchop-Keuy [Çob-Köy] visited the village, and after beating the Pope, Fotios, and threatening the inhabitants, called upon them to evacuate the place. In May 1915, fifty Turks under the orders of the Chief of the Gendarmerie, accompanied by many Turkish immigrants, entered the village, and demanded of its inhabitants to evacuate the village within three days, after which they plundered it and carried off Dhimos Haritos, who was found dead in the woods the next day, bearing six wounds. Sometime after the villagers returned to their homes.

- LALAKEUY [Lalaköy]. — The inhabitants were forced to evacuate the village and took refuge in Kastritza, Farasli, and Kashim Pasha (Harioupolis).

- KARABOUNAR [Karapunar]. — After the re-occupation of Adrianople by the Turks, this village was brutally pillaged, especially by the well- known miscreants of the adjacent village of Maksoutli, at the head of whom were Kel Tahir, Neki Ahmet, and Hussein, well-known characters, and renowned of old for their exploits. By threats they managed to extort Ltq.lOO (in gold) from the poor villagers.

At the time of their deportation the Christian inhabitants of Karabounar [Karapunar] (September, 1915) were given short notice to depart and were dispatched by Government carts, escorted by gendarmes under the superintendence of the members of the Young Turks’ Committee, so that they scarcely took anything away with them.

- MALCOTSI. — After the second Balkan War, as soon as the Bulgarians retreated, the Turks of the vicinity, especially those from the village of Mandritsa, did great damage to the place, the Christian inhabitants of which, fearing lest they should be molested by the Turks, had for the greater part sought refuge in Bulgaria and Greece. Some few families that remained over were deported by the Turkish authorities to the village of Doghankeuy [Doğanköy] of the Malgara district. The Church and Holy Communion were desecrated by the Turkish immigrants. Shortly after, the Church was demolished, and the stones sold by the Turkish Government through the Mudir of Tchop-keuy, Ahmed Teufik Bey. These very stones, which Christian women were forced to carry, were used to build the mill and stables of the late Hadji Emin Agha, chairman of the branch office of C.U.P. (Committee Union and Progress). The same lot befell the houses, fields, and fortunes left behind them by the deported Greeks, which were given gratuitously to the Turkish immigrants from Greece and Serbia, who had settled in Malkotsi since the European War broke out.

Two-thirds of the Christian population deported to Doghankeuy were obliged to take refuge in several villages of the district of Malgara and Ouzounkeupru [Uzunköprü], as they could not earn a living in the former place. Many families also went over to Bulgaria.

The inhabitants of Malkotsi suffered from the persecution of the Mudir of Tchopkeuy. At Easter, 1915, in the night, he gathered the peasants in the village church. Standing before the Altar, whip in hand, he swore at them, thrashed innocent women and children, and Pope Papa Christo Economou, in order to force them to surrender the deserters who did not exist. He whipped and imprisoned Athanassi, son of the Pope, and was the cause of his death; and lastly, it was he who forced the villagers to give the sum of Ltq. 100 for the pretended erection of a Hospital at Adrianople, of a Mill at Tchop-keuy [Çob-Köy], and ships for the Turkish fleet, etc.

- KIRKEUY [Kırköy]. — At the time of the re-occupation of the village by the Turks, the Christian population suffered equally at their hands. Some 110 notables were then expelled, and their fortunes confiscated by the Turkish Government. Their landed property was handed over to the Turkish immigrants. Those of the Greek inhabitants who evaded exile became the victims of the rapacity and greed of the Turkish Government and the Turkish notables in their immediate vicinity.

Towards the middle of September, 1915, the inhabitants were deported in the same manner as those of so many other villages, and took refuge in Doloukeuy [Doluköy] (of Malgara).

- KAVADJIK [Kavacik]. — During the second Balkan War, this village was plundered and then set fire to by the Turks, especially those of the Turkish neighbouring village of Hamidie [Hamidiye], in consequence of which its inhabitants suffered endless deprivations and atrocities. The majority of the houses and the village Church were burnt, and no less than fifteen Greeks were savagely put to death.

Owing to these terrible conditions, the majority of the Greeks dispersed over the other Christian villages of Ouzoun Keupru [Uzunköprü]; some went to Bulgaria, and some to Greece. On the 20th of August, 1915, the remaining families were expelled by the Turks and deported to the Malgara region. Some established themselves in the village of Tartarkeuy [Tatarköy], some in that of Repitz. (…)”

Excerpted from: Ecumenical Patriarchate: Persecution of the Greeks in Turkey, 1914-1918. Constantinople [London, Printed by the Hesperia Press], 1919, pp. 30-37

After the Armistice (Nov 1918-1920)

“It must be specially noted that from the conclusion of the armistice up to the present day, the Turks of Rodosto held a provoking and menacing attitude toward the Christian population of the city. There even came a time when the Christians shut their shops up early and confined themselves at home, fearing assaults on the part of the Turks.

At the end of May, 1919, three Albanian Turks, guarding Tsikili farm, on the Tsads-Tyroloe road, killed two young men of Tsads, whose clothes and ears they sent to his town, to frighten the peasantry, and whose corpses they gave to the dogs of the farm for food.

On the first days of September of the same year [1919], three shepherds of the same town, named Stavros Lazou, Authologos Apostolou and Anastasios Kehaghias were returning from Tsado to their sheepperi (?) near Skereki from where they were caught by 16 constables who took them to the forest. The first managed to escape but the two other men disappeared. On the 11th of the month, they were found killed, the belly of the one had been torn open with a bayonet and the body of the other was mangled.”[10]