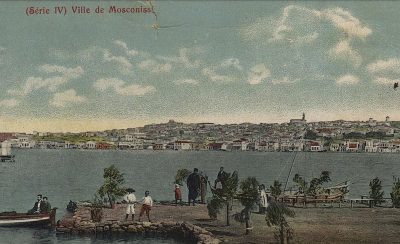

The kaza’s administrative center of same name, Ayvalık (Grk. Kydonies), is a seaside town on the northwestern Aegean coast of Turkey. It is surrounded by the archipelago of the Ayvalık Islands (the largest of which is Moschonisi(a), literally ‘The Perfumed Islands’; Trk.: Cunda Island, or Alibey Island) in the west, and by a narrow peninsula in the south named the Hakkıbey Peninsula. The constant threat posed by Arab and Turkish piracy in the region did not allow the islet settlements to grow larger and only Moschonisi could maintain a higher level of habitation as it is the largest and the closest islet to the mainland. The ancient town of Kydonies/Kydonia is now a village, situated opposite of the island Lesvos, not far from Ayvalık, which was built as the chief seaport in Northwest Asia Minor in the third decade of the 19th century.

Altınova and Küçükköy are other southern neighborhoods of Ayvalik, which are away from the town center. The Greek island of Lesbos (Mytilene) is further west of Ayvalık. The region is under the influence of a typical Mediterranean climate with mild and rainy winters and hot, dry summers.

Ayvalık was located in the ancient region of Aeolis. The ruins of three important ancient cities are within a short driving distance: Assos and Troy are to the north, while Pergamon is to the east. Mount Ida (Trk.: Kaz Dağı) which plays an important role in ancient Greek mythology and folk tales (such as the cult of Cybele; the Sibylline books; the Trojan War and the epic poem Iliad of Homer; the nymph Idaea (wife of the river god Scamander); Ganymede (the son of Tros); Paris (the son of Priam); Aeneas (the son of Anchises and the goddess Aphrodite) who is the protagonist of the ancient Roman epic poem Aeneid of Virgil) is also near Ayvalık (to the north) and can be seen from numerous areas in and around the town center.

Toponym

The ancient Greek Aeolian port-town was originally called Kydonies (Grk.: Κυδωνίες – ‘Place of Quinces’) and it served surrounding Greek Aeolian cities, such as Pergamon. Since the Ottoman era, its official name changed to Ayvalık. The town’s predominantly Greek population, however, continued to use its ancient name Kydonies and the Hellenized version of its new name: Aivali (Αϊβαλί).

Population

The kaza of Ayvalık consisted of the two Greek Orthodox dioceses of Aivali and Moschonisi. Before the First World War, the Diocese of Aivali comprised 26,387 Greek Orthodox Christians in six communities[1] and the island of Moschonisi an exclusively Greek population of 6,000 souls.[2]

In 1891, there were 21,666 Greeks and 180 Turks living in the town of Ayvalık. According to a report of 4 September 1915 by Dr. Herbert Schwörbel, the Second Dragoman (interpreter) at the German Consulate at Saloniki, there was a pre-war population of 36,000 residents in the almost exclusively Greek town of Kydonies. A third of the population had then escaped to the near Greek island Mytilene (Lesvos) after the onslaught of 1914. In his report, Schwörbel mentioned a remaining population of “only about 22,000 exclusively Greek inhabitants”.

As of 1920, the Ayvalık’s population was estimated at 60,000[3], still consisting almost entirely of Greeks until 1922. Ayvalık was an important cultural center for the Greek-Orthodox community of the Ottoman Empire, an unique stronghold of Hellenism.

Following the Turkish War of Independence, the Greek population and their properties in the town were forcibly exchanged by a Muslim population from Greece, and other formerly held Ottoman Turkish lands, under the 1923 bilateral agreement for the compulsory Exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey. Most of the new population that replaced the former Greek Orthodox community were Greekophone Muslims from Mytilene, Crete and Macedonia. One could still hear Greek spoken in the streets until recently. Many of the town’s Greek Orthodox churches have been converted into Muslim mosques.

Notable Greek Aivaliotes

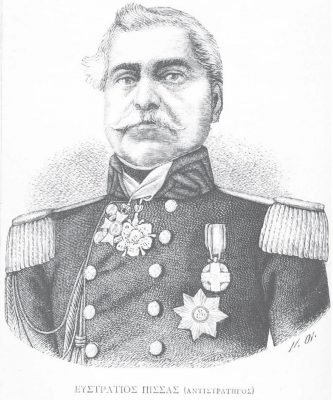

- Efstratios Pissas (Ευστράτιος Πίσσας, born Aivali, 1797 – 1 January 1885), revolutionary of the Greek War of Independence and later Lieutenant general

- Konstantinos Tombras, operator of the first printing press in the town and the first press in Greece. In 1819 he started, with font creator Konstantinos Dimidis, one of the area’s first Greek print shops, and produced books and the city’s main newspaper “Kirix”

- Grigorios, or Gregory (Orologas) of Kydonies (Γρηγόριος Ωρολογάς, 1864–1922), Metropolitan of Kydonies, genocide victim; arranged for majority of Greek population to leave for Greece via the International Red Cross, but was himself executed by Kemalist authorities

- Georgios Tombras (Γεώργιος Τόμπρας, Aivali, 1 January 1878 – Chalandri/Greece, 20 April 1963), soldier of the Macedonian Struggle and First Balkan War

- Photis (Fotis) Kontoglou (Aivali, 8 November 1895 – Athens, 13 July 1965); writer, painter and iconographer

- Elias Venezis (Ηλίας Βενέζης, i. e. Elias Mellos; Aivali, 4 March 1904 – 3 August 1973), novellist

- Stratos Pagioumtzis (Στράτος Παγιουμτζής; Aivali, 1904 – New York, 16 November 1971), rebetiko singer

History

After the Byzantine period, the region came under the rule of the Anatolian beylik (principality) of Karası in the 13th century and was later annexed to the territory of the Ottoman beylik, which was to become the Ottoman Empire in the following centuries. In Ottoman times, Ayvalık had a small port, exporting soap, olive oil, animal hides and flour. The British described Ayvalık and nearby Edremid (Edremit; Balıkesir) as having the finest olive oil in Asia Minor. They reported large exportations of olive oil to France and Italy.

The settlement of Ayvalık, which gave the name to the modern municipality, was founded around 1600 near the former ancient settlement of Kisthene (Κισθἠνη). As a result of the general insecurity in Greece and the islands after the Orlov Revolt of February 1770, there was an influx of people from all parts of Greece and the islands as far as the Peloponnese and the Ionian Islands, which were still under Venetian rule. Ayvalık was inhabited by Greek Orthodox settlers from all over the Aegean region. The city took a huge economic boom in the 18th century, based on olive cultivation and trade in olives and olive products. The Derebeys from the Karaosmanoğlu family, who dominated Western Asia Minor, encouraged the settlement of Greeks, mostly from the Aegean islands, among other things, by granting tax privileges.

However, “(…) Kydonies did not get its identity until 1773, when Ioannis Dimitrakellis (1735-1791), a priest with the rank of Oikonomos, managed to obtain from the Ottoman emperors a firman (decree) of autonomy. It included the right for the Kydoniates to run their own affairs (from civic governance to social services) and to have only a token presence of Turkish citizens and government representatives (i. e. judges) in the city. (…)

Fr. Dimitrakellis, who had been educated in Mt. Athos, was politically astute, strict, ambitious and a visionary. Under his leadership, the city developed voting wards (centered around the city’s 11 churches), a hospital (with mental health and communicative diseases units), an orphanage, a nursing home, three elementary schools (or schools of “common letters”), boys’ and girls’ high schools and the famous Greek Language School of the Panagia ton Orphanon (an institution that was between secondary and higher education), which had a library, physical science labs and a dormitory.

Aivali’s preoccupation with education soon made it the center of Greek letters in Asia Minor, and students as well as famous teachers began to come to the city. (…)

(…) The social infrastructure was supported by port fees and through a unique form of stewardship devised by Fr. Dimitrakellis–the “psychomeridion” or “apportionment of the soul.” In this way individuals or families with social conscience could give a portion of their wealth to common city causes.”[4]

Ayvalık became a center of Aegean Hellenism. This era ended with the Greek War of Independence, during which it was destroyed. After the war, the survivors gradually returned and after the Tanzimat reforms (1839-1876), the town experienced a renewed boom. Ayvalık already had a printing press, a pharmacy in the 19th century and several consulates were located here, including the German, French and Dutch consulates. There was an academy and various high schools and vocational schools. The still existing mansions give an idea of the prosperity of the city at that time. Due to its special position, the Ayvalık retained tax rights and no dues had to be paid to the Ottoman government. In 1908 the city became the seat of an Orthodox Metropolitan. The first, and effectively last, Metropolitan in office was Gregory (Orologas) of Kydonies.

Greek War for Independence

The locals contributed with their economies to the Greek struggle for independence, including the famous ‘Psorokostaina’ (or Psarokostaina, i.e. Panoraia Chatzikosta; see below).

In 1821, following riots, the Greek Christian male population was massacred by the Ottomans, and the women and children were sent into slavery. As reported by the then British Ambassador Lord Strangford, Osman Pasha, accepted the submission of the Aivaliotes, until he could get fresh instructions from Constantinople. However, a squadron of Greek insurgents appeared, inducing the inhabitants to hope that it had come to their rescue, and that they might make another attempt at revolt with better success. They accordingly rose en masse, and about fifteen hundred Muslims were killed. But the squadron (the appearance of which in the bay had been merely accidental) having in the meantime sailed away, the Turks recovered their courage, and an indiscriminate massacre of the Greeks followed.

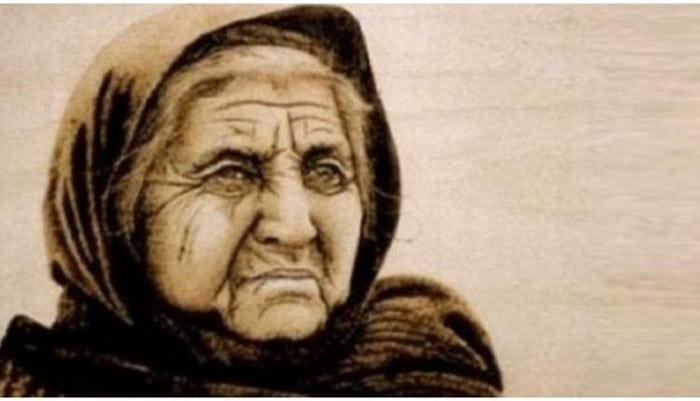

Maria Korologu: Psorokostaina a Real Figure in the Greek War of Independence

Greeks use the word “Psorokostaina” to describe misery and poverty. However, according to folk tradition, Psorokostaina was a real person — and even a heroic figure — during the Greek War of Independence.

According to the Argolikos Archival Library of History and Culture, in 1821, the town of Kidonies in Asia Minor was destroyed after a failed revolutionary movement, and its population was slaughtered.

Those few who survived the Turks left their beautiful town to go to the island of Psara.

Panoraia Chatzikosta, a beautiful lady having a large fortune, managed to save herself from the destruction. A sailor helped her into a boat which took her to the small island of Psara.

Panoraia Chatzikosta, also called “Psarokostaina” or “Psorokostaina,” after the island she fled to, saw her husband and children killed in front of her very eyes by the Turks.

In Psara, where she found herself destitute and all alone, she was helped and protected mainly by Benjamin of Lesvos, a professor at the Academy of Kydonies. Panoraia soon left Psara and went to Nafplio, the capital of Greece at the time, along with Benjamin, who also went to live there.

At first all went well, and she was able to live as his household servant. The professor and philosopher gave lessons to make a living in Nafplio. But in August of 1824, Benjamin of Lesvos tragically died of typhus.

Psorokostaina taking care of orphans

After his death, Panoraia worked as a porter and a washerwoman, while she eked out a living while receiving charity from the people of Nafplio.

During the years of the Greek Revolution, there was understandably an increasing number of orphans in the country, and many were sent to Nafplio.

Despite her problems, Panoraia asked to care for some of the children, and soon took several orphans under her protection. She went from house to house begging in order to feed her frowning brood of children. In 1826, a fundraiser took place in Nafplio for the area of Missolonghi, the site of a great battle in the War. But because of the general poverty of the Greek people at the time, there was very little raised for suffering Missolonghi.

Suddenly, the poorest woman of all, the widow called Chatzikostaina and Panoraia, took off the silver ring she was wearing, and laid it with one coin on the table that the fundraising committee had set up in the square of the city.

But this was only the beginning. After seeing the incredible sacrifice of the impoverished widow, everyone began approaching the table, and it was soon covered with silverware and coins.

Psorokostaina did not only give concrete lessons of patriotism, but of humanity as well, since she shared her little income with the fighters’ orphaned children after herself suffering the worst misfortunes that life had to offer. When Ioannis Kapodistrias founded an orphanage in Nafplio, she offered to wash the children’s clothes for no pay at all. She died several months after the institution was opened and at her funeral, her coffin was accompanied by the children of the orphanage.

Source: The Greek Reporter, 12 March 2021, https://greekreporter.com/2021/03/12/psorokostaina-real-figure-greek-independence-war/

Destruction

1909

On 25 June 1909 the Ottoman Lloyd, No. 146 reported a visit of the Ecumenical patriarch Joachim III (the Magnificent) to the Ottoman commander in Chief, Mahmut Şevket in order to protest against “murders and violence”[4] against Greeks in the Ionian town of Kydonies (also Kydonia; Ayvalık in Turkish). The generalissimos used the opportunity to articulate his discontent with the irredentist development at Crete that he linked with the activities of Greek associations (Syllogoi) in Asia Minor: „All agree about this. I speak about the societies and syllogoi. No, we cannot stand this situation any longer. We will break your heads; we shall annihilate all of you. Either we shall be lost or you!”[5] The Greek daily Embros (Athens) of 24 June 1909 concluded:

“Neither the conduct of Şevket towards the Patriarch nor the murders and violence in Kydonia, nor the despotism in Xanthis is as such of significance. These are events, deriving all from the same reason. The Turks have decided to lead a war of annihilation against the Christians of the Empire, and of course they started, where they face the strongest enemy inside Turkey and the smallest resistance outside the country.”[6]

Before WW1

Although the population ‘exchange’, which the Ottoman Empire intended already after the Balkan Wars, did not materialize at that time, the kaymakam of Bergama (Pergamon) and Rahmi, the vali of the Aydın province[7], both refugees from Thessaloniki, nevertheless increased the pressure on the Greeks of the Aydın province and on those from the Kydonies (Ayvalık) area; after Smyrna, Kydonies was the largest Greek city in the region. By order of the kaymakan, the olive groves that formed the base of the existence of Ayvalık, were expropriated and assigned to Muslim refugees from the Balkans. Although they no longer possessed them, the Greek Aivaliotes were taxed on these groves. Because of the alleged danger of espionage, the Greeks were no longer allowed to work as skippers or pilots.

“The retreating Turkish army (1912) murdered many of the inhabitants, among whom was Pope Lazaro, eighty years old. In 1914, the same methods were resorted to, to terrorize the inhabitants of this village. On the 4th February (o.s.), George Carayannakis was assassinated, and although the assassin was known, the authorities arrested, under pretext of investigation, all the notables of the village. Then, after the inhabitants being terrorized by Yousouf [Yusuf] Bey of Loule-Bourgas [Lüleburgaz; Bergula; Grk.: Arkadioupolis], Djounni Effendi, chief surveyor, Osman Effendi, head of the Gendarmerie, and Eden Effendi, tax-collector, as well as by the gendarmes themselves and irregulars, they were forced to ex-patriate themselves. In March, 1914, there was not a single Greek in the place ; all had sought refuge in Greece. Their houses, fields, furniture, and in general the fortunes of these peasants were handed over to the Moslem emigrants of Greek and Serbian Macedonia.”[8]

“The same organized persecutions as applied elsewhere had been enforced by the official authorities, since the month of May, 1914, in the island of Moshonissi (population 6,000 souls, exclusively Greek) owing to which the economic and commercial life of the community soon became problematic for the inhabitants, and resulting finally in their departure from their native soil.

Those who remained on the island were condemned to a lamentable fate by the local authorities, for the arrival of a band of insurgents in the island added to the persecution of the inhabitants. The inhabitants were then deported to Aivali without taking anything with them.

In Aivali they shared the same fate of oppression with its inhabitants until they were all deported, and scattered among the Turkish villages of the vilayet[s] of Smyrna and Broussa. There they lived for twenty long months, daily subjected to all kinds of persecutions and dying in great numbers.

Real acts of vandalism followed the expulsion of the inhabitants of Moshonissi. Churches were turned into warehouses and stables, the lamps and holy images in them were broken, paintings of art destroyed and houses rendered uninhabitable.”[9]

During WW1

According to a report of 4 September 1915 by Dr. Herbert Schwörbel, the Second Dragoman (interpreter) at the German Consulate at Saloniki, there was a pre-war population of 36,000 residents in the almost exclusively Greek town of Kydonies. A third of the population had escaped to the near island Mytilene after the onslaught of 1914. In his report Schwörbel mentioned a remaining population in Ayvalık of “only about 22,000 exclusively Greek inhabitants”, which was twice deported during WW1, in July 1915[10] and in April 1917.

Schwörbel, who travelled twice in official missions to Ionia during summer 1915, reported also the presence of concentration camps[11] along the Soma-Pandarma railways with Greek women, children and old peoples; they were deportees from the Marmara coast, entirely left to themselves without food and accommodation:

“Because the government does not care at all about feeding these masses and because under the recent conditions the possibilities for the deportees to find work or to earn any money are scarce, the daily casualties are high, as the railway physician of the Soma-Pandarma line confirmed.”

Schwörbel concluded: „With the exception of Aivali and Smyrna with its environs the entire Greek civilization, which flourished until recently at the west coast of Asia Minor is destroyed. The reason lies in the Islamist movement in Asia Minor, initiated in the beginning of May last year by the recently immigrated refugees from Macedonia and Mytilene and stirred up by the general governor of Smyrna, Rahmi Bey, with the aim to expel the Christian populations from Asia Minor and to replace them with Muslims.“[12]

In May 1917, with the help of German forces under the command of Otto Liman von Sanders, 12,000-23,000 Greeks were deported from Ayvalık to the inner parts of Anatolia.[13] Of the first 2,500 or so deportees from Kydonies, a scant tenth – about 200 – died on their 42-day forced march to Anatolia.[14] As the reason for his approval of Turkish deportation intentions, Liman cites “continuing treason and espionage traffic” of Ayvalık residents with the Entente forces.[15] Commenting on this, the German ambassador added: “As was to be expected, the evacuation of so many Greeks (the figures vary between 12 and 20000) caused a great stir and greatly embittered the Greek element. The Greek envoy paid me a visit to attempt to see if I could not reverse the evacuation order. I had to explain to him, however, that in view of the unconditional military necessity of the measure advocated by Marshal Liman von Sanders, I lacked any means of interference. He said that Liman von Sanders’ proven pro-Greek sentiments in many cases vouched for the fact that he had decided to take such a drastic measure only under pressure of extreme necessity. The envoy pointed out that the matter would also exert a very bad influence in Athens, detrimental to the king’s policy, since such a measure, hostile to the Greeks on a large scale, had this time not emanated from the Turks, but even, with quite a bit of reluctance on the part of the Turks, from the German supreme command.”[16]

The oil industry in Ayvalık suffered during the First World War due to the deportation of Christian populations in the area, who were the primary makers of olive oil. Most importantly, however, the functioning of the economically vital oil mills in Ayvalık was not to suffer as a result of the deportation of the Greeks. In fact, as early as July 1917[17], Liman von Sanders had ordered the businessmen among the deported Greeks from Ayvalık to return, “because otherwise the economy would have collapsed.”[18] Subsequently, 4,500 Greek families were brought back to the area in order to resume olive oil production. Although these repatriated Greeks were receiving wages, they were not allowed to live in their own homes, but were kept under official surveillance.

On 17 October 1917 Frank W. Jackson, chairman of the U.S. Relief Committee for Greeks of Asia Minor announced in New York, that “(…) more than 700,000 Greeks have fallen victim to persecution in the form of death, suffering, or deportation. ‘The story of the Greek deportations is not yet generally known. (…) Quietly and gradually the same treatment is being meted out to the Greeks as to the Armenians and Syrians. (…) There were some two or three million Greeks in Asia Minor at the outbreak of the war in 1914 subject to Turkish rule. According to the latest reliable and authoritative accounts, some seven to eight hundred thousand have been deported, mainly from the coast regions into the interior of Asia Minor. (…) Along with the Armenians most of the Greeks of the Marmora regions and Thrace have been deported on the pretext that they gave information to the enemy. Along the Aegean coast, Aivalik stands out as the worst sufferer. According to one report, some 70,000 Greeks have been deported towards Konya and beyond. At least 7,000 have been slaughtered. The Greek Bishop of Aivalik committed suicide in despair’.“

Excerpted from: Greek persecution in Turkey; „The Scotsman“, November 6, 1917, p. 7

Diocese of Aivali: Harrassment, expulsion, prohibition of emigration, eliticide

“Already at the outbreak of the Balkan War, acts of pillage and robbery ‘had started in the town and diocese of Aivali (six communities, 26,387 inhabitants), forcing the Greek element to leave. The boycott spread all over the country, followed by persecutions. On the 22-24 May, 1914, the inhabitants of the villages of Yaka-keuy [Yakaköy], Gumetch, Kemerkeuy [Kemerköy], and Ayazmati fled to Aivali with their children in their arms. In consequence of the declaration made to them by the Caimacham [Kaymakam] of Gumetch, to the effect that he would take no responsibility whatsoever, he advised the peasants to temporarily quit their dwellings until things settled down again, and they all went to Aivali. On their way, however, they were attacked by wild gangs of armed Turks, who stripped them of their money and clothes, beat them, and violated four girls. They were then forced to embark on benzine steam launches and lighters, and sent to Mitylene.

Shortly after the evil spread to the whole Aivali Region, which was plundered by the Turkish bands to the extent of thousands of pounds of damage.

After the evacuation of the four aforementioned villages, and the pillaging of the farms in the neighbourhood of Aivali, the village of Yenitsarohori was attacked on the 27th May, 1914, by Turkish immigrants, who set fire to seven points simultaneously. Terror stricken, the peasants fled to the town. One thousand five hundred of them, in spite of the assurances of the authorities as to the safety of their lives, honor, and property, took refuge in Mitylene. The situation of Aivali itself became very critical. The evacuation of the town was expected at any moment.

On one occasion, Nouri Bey, chief of the gendarmerie, told Gregory, the Metropolitan of Aivali:

‘The Government does not expel you, but we will not oppose the desire of the Nation. Only two towns now remain, Smyrna and Aivali ! You will also have to go.’

In consequence of the foregoing events the Metropolitan of Aivali addressed the following note to Talaat Bey, Minister of Interior, then staying at Aivali.

The following is a translation of the letter.

‘Your Excellency,

As the spiritual head of the inhabitants of Aivali, exclusively Greek Orthodox, I beg to bring to your notice the sad events which have taken place these last days, and which have so moved the whole population, and to acquaint you with the real causes that gave rise to them.

On Wednesday last, notices, bearing the seal of the Governor, Nedjim Oulah Effendi, were posted up. The public were informed that emigration was prohibited. As, however, the sentence ‘emigration is prohibited’ implies that a current in favor of emigration did exist, allow me to throw some light on this question. Not a single citizen, whether big or small, rich or poor, had ever thought of expatriating, as it is given to be understood by the official notice. On the contrary, every one’s mind was bent on his work. I feel confident that neither the Governor, nor the Officer in Command, and the other officers of the army, the President of the Interior Court, the delegate of the Public Prosecutor, the Directors of the Custom House, of the Public Debt administration, as well as the Chiefs of the Gendarmerie and the Police, will ever refuse to certify authenticity of this fact that such was the real state of mind of the population, and it is only because I firmly believe this that I appeal to the testimony of all the above high officials to establish the truth of my assertion.

Nevertheless, no later than ten days ago, it was reported that the Christian inhabitants of Karaghatch, and the neighbouring villages, Gumetch, Yaya, Kerem, and Ayasmati, had been forced to expatriate by unknown persons, who, moreover, seized their property including their furniture, horses and cows, and in fact everything they possessed.

The majority of the peasants thus expatriated took refuge in Aivali. They applied to the Bishopric declaring they had been forced to expatriate, and asking for assistance to enable them to return to their homes in order to force the inhabitants of Aivali to emigrate. Also the Turks attacked the Aivaliets [Aivaliotes] working in their fields, and plundered their sheep, oxen and homes. After having complained to the Governor, they came to the Bishopric, where their statements were taken down in writing.

Aggressions and plunder have now spread far and wide, so that the farms of Aysasmati belonging to Aivaliets, were plundered and thousands of sheep carried away and important fortunes stolen. Churches were ransacked and holy images desecrated. In the town of Aivali itself certain Moslems made it a point to advise the Christians to deport, that being the only means of saving their lives. But although the Aivaliets suffered greatly from these oppressions, they felt they could rely on the Government for protection, and it was this confidence that prompted them not to expatriate.

The village of Yenitsarchori, twenty minutes from here, has now been attacked, and armed Moslems of the vicinity tried to burn it by setting fire to the doors of some houses. But on the morrow at dawn, all the inhabitants with their families abandoned the village and proceeded to Aivali.

And although the Aivaliets are terror stricken by these events, they still cannot make up their minds to emigrate and abandon their town and property which, at the price of much toil and activity, they had rendered so flourishing. They declare they cannot emigrate to a foreign land, and so abandon their fortunes, churches, and the tombs of their forefathers. They have decided to remain in their country and to continue to live there as Christians with the same feelings of loyalty towards the State as hitherto.

In making to you these formal declarations on behalf of the Christian inhabitants, I request that you will be so kind as to take the necessary steps to avoid a repetition of these attacks and plunders on the part of Moslems of the neighbouring villages, with whom the Christians have so far lived in harmony, that the plundered goods and cattle should be returned to their rightful owners, the young girls taken by main force be released, and, lastly, that the culprits be severely dealt with and punished according to the law.’

In response to this appeal, the next day the sub-governor issued a proclamation to the effect ‘that the people should attend to their business, that the Greek Ottomans need not have any apprehension regarding their expatriation, which is strictly prohibited.’ Despite these assurances however, the conduct of the Government proved that the contrary was to be expected, and that the expulsion of the inhabitants was imminent.

Firstly the town was closely blockaded. Insecurity prevailed in the country districts. Armed bands of Turks, recruited and led by civil and military officials, terrorized the country, murdering and committing atrocities. The small houses in the fields, vineyards, or olive plantations were either set fire to, or demolished, and the agricultural implements stolen.

Even in the town itself, the lives, honor and property of the population were threatened, with a view to creating an intolerable situation and so oblige them to expatriate.

Churches were desecrated, chapels demolished or concerted into Mosques, stables, or coffee houses. Graves were dug up, and the bones of the dead scattered abroad. The advice to the Christians from Government officials was to leave for Greece as the only means of salvation.

The situation gradually became worse, and in order to increase the existing panic of the inhabitants, the Government arrested twelve of its notables and deported them to Balikesser [Balıkesir].

The sub-governor established in the town twenty Black Sea pirates (Lazes), who, armed to the teeth, roamed about the streets, subjecting the inhabitants to all kinds of persecution. They further plundered their houses, and divided the spoil with the officials in authority.

The inhabitants, numbering 7,000, unable finally to endure any longer such sufferings, decided to abandon their homes and fortunes, and emigrate from their native soil.

There was no end to the martyrdom to which the remaining inhabitants were subjected. Their life, honour, and their fortunes, were simply considered as playthings by the Moslems.

An attempt at general deportation was made on the 15th September, 1915. Two hundred and seventy-two citizens of all ranks, including the Metropolitan, the grand Vicar and three priests, were arrested, and conducted under military escort to an unknown destination. However, some days later, they all returned from Klisse-Keuy [Kiliseköy] to which place they had been deported.

It now became evident that Aivali, this stronghold of Hellenism in Asia Minor, was doomed to ruin, for on the 15th of March, 1917, the expulsion of the Aivaliets began. The town was occupied by three battalions of troops from Soma, by order of the Military Commander of the region, Vahid Bey, which arrived in the evening. Before dawn, strong detachments overran the different quarters of the town, and arrested all its male inhabitants from 15 years upwards. The women and children were turned into the streets, and only five minutes time was given them in which to remove their furniture and clothing. The gradual evacuation of the town was continued under these auspices, and completed by the 3Oth April, 1917.

The population was scattered over the Broussa [Bursa] and Smyrna [Aydın] vilayets and the district of Karassi [Karasi]. About 256 persons were withheld exclusively for the requirements of the army, as well as two priests and the Metropolitan who were subjected to very hard treatment.

The Metropolitan of Aivali was kept in close confinement in his Bishopric from the 23rd January to the 1st of May, 1917, and was then sent to Smyrna under escort. He was imprisoned and deprived of every communication with the outside world until the 19th October, 1919, the date of the conclusion of the Armistice.

The misery of the poor people would be hard to describe after they were scattered among the inhospitable, miserable Turkish villages, where they were severed from every other Christian element besides being exposed to every kind of privation.

The cyphered order of Talaat to the Provincial Authorities, as reported by a Turkish high official, contained two words only: ‘Feft-i-medeni’ (civil murder). And in carrying out this order, no exception was made with regard even to forty-one orphans, in charge of the Grand Vicar of the Bishopric, Arsene Menexes, who were conducted to Biledjik [Bilecik]. The pre-eminently Greek town of Aivali was destroyed, the altars of the churches were desecrated, its chapels demolished or turned into stables, and its shops plundered and left in ruins.

On the 27th of July, 1917, the Metropolitan of Aivali writes: ‘The plundering of the establishments and shops by the soldiers and others which lasted the whole of the Ramazan, still continues. No one interferes with the plunderers, who having all the means of transport at their disposal, are allowed to carry away their spoil. Thus, with the acquiescence of the Authorities, all the wealth of the Christians has passed into Turkish hands, and has been carried away from the town.

The government requisitioned, on the plea that they were required for the Army, thousands of copper utensils, chairs, mattresses, coverings, etc., deposited by the deported Greeks in their churches, bringing about the complete ruin of the Christians by depriving them of everything they possessed. These operations are now being officially carried out by the military authorities, on the basis of the Law in force, according to which it is allowed to lay hands on, or pay onerous prices (fixed by a terrorized commission) for anything that the Administration of the Army can make use of among the ‘abandoned fortune’, as our property is called. The question now arises how will the citizens, on their return, be accommodated, and their existence rendered possible, if the scanty effects that escaped plunder and were safely deposited in their churches, are being officially confiscated by the Authorities?’

The pre-meditated evacuation of this town by the Young Turks was carried out by the German General, Liman von Sanders Pasha, who, from the very moment he was appointed head of the military re-organization commission, and later on in his capacity of Commander of the 5th Army Corps, incessantly pursued the annihilation of the Greek population of the sea coast of Asia Minor. There is no possible doubt whatever of the complicity of the General with regard to the deportation of the Aivaliets and the ruin of Aivali. There exist clear and positive declarations of authorized persons and those of the said General himself, which throw sufficient light on the question. These facts are mentioned in a report of the Metropolitan of Aivali, who can produce the necessary evidence in support of his assertions.

The compiling of a complete list of persons who were murdered or otherwise persecuted is somewhat a difficult matter. Nevertheless, the following account will convey an idea of the extent of the savagery of the Turks, and the martyrdom at their hands of the unfortunate Ottoman Christians.

During 1914.

On the 20th May, Dim. Kos. Vaxevanie was murdered by the Turks of Tsakalia. On the 23rd of the same month loannis Halvadjis. On the 2nd June, Haralambos Koumparakis, on his way to his business, was killed near Kourou-Tchesme [Kuru-Çeşme]. On the 3rd June, George Sakali, Dem. Boyadjis, and Const. Carabounari, were carried away by the Turks and murdered. The same day P. Sahanas, on his way to his garden, was killed. On the 5th June Efstratios Marinos went out to reap. He was also murdered. N. Kazakhs was on his way to his farm when lie was carried away by the Turks and murdered. His body was found without head, hands or feet.

On the 11th June Panayiotis Voulgarelis was found murdered in the well of his farm, his body bearing many signs of knife wounds. Athan. Kouzamakis gave notice that his brother Triantafilos, along with Zaharia Limness and Efstratios Kardharas, who went out together some twenty-nine days before to Salahlar, disappeared. Christos Karafonias, eighteen years old, went out to the fields to cut grass. He was killed by the Turks on the 25th June, his companion George Kiriki managing to escape. Kyriazis Hadji Tdiobanis was killed by Turks on the 8th of July while he was working with his two brothers, Efstratios and Photios. Besides these, the names of a host of other victims appear in the list so far known.

After the evacuation of Aivali the following outrages took place:

Three young girls, Tassi, Maria, and another Maria, aged respectively seven, nine, and twenty-two years, were violated by Turks at Mouratza. Athanasse Yerondelis, fifty-five years old, was beaten to death close to the village of Boyatitch [Boyatiç]. The next day his corpse was found torn to pieces by the dogs. George Yandounis, sixty years old, was thrown by the cart-drivers in the river Lompatza, and drowned. A woman, Angheliki N. Ktistou, was empaled by three Turkish women near Mouratza. Aristea Martini, fifty years old, was beaten to death by a gendarme at Akkeuy [Akköy]. Dem. Kakavros, sixty years old, mercilessly beaten to death at Tourkmen [Turkmen] by a gendarme. Hariclea Marangheli, fifty years old, after having her eyes put out at Koyounlou [Kuyunlu] by Turks, went mad, and died soon after, George Arpayianos, forty-five years old, was killed from club blows by the cart-drivers, because, being sick and infirm, he could not walk. Constantine Manolias Moschanissios was beaten to death. Tasitsa Pseftochristou, thirty years old, was strangled with a rope by the cart- drivers on the road to Tourkmen in the very presence of the gendarme whose care she was in. Georges Tsoukalas, four years, was tied behind a donkey and beaten the whole way to Tourkmen, which resulted in his death soon after. A further list of names follows of persons of both sexes deliberately done to death by the Turks.”[19]

1922: Death Marches and Slave Labor

Ayvalık was controlled by the Hellenic Army on 29 May 1919 and consequently taken again three years later by Kemalist forces on 15 September 1922.

Violence against the Greek residents of Kydonies began in August 1922, when the first irregular bands of the Turkish army entered the city. Martial law was declared. During the following days, all adult males were arrested and driven on a forced march away from the city. On the road leading to the village of Freneli (near modern Havran), they were shot down with machine guns. The Metropolitan Grigorios (Gregory) Orologas tried to save the remaining Christians in the city by intervening with the Turkish authorities, which did not hesitate to humiliate him. After 6,000 of the inhabitants of Moschonesia were also massacred, including Metropolitan Ambrosios, the later martyred and canonized Metropolitan Grigorios secretly contacted the American Red Cross for help. The Red Cross secured ships from Lesbos in order to carry the women and children to safety. The Turkish authorities agreed to this proposition. As a result, the largest part of the Greek Orthodox population of the city – 20,000 out of 35,000 – were saved by Greek ships sailing under the American flag.

Although he encouraged all the priests of the city to leave, Metropolitan Grigorios stayed back. On 30 September 1922, while all the priests were gathered on the waterfront ready to depart, Turkish authorities arrested them. Authorities also detained Metropolitan Grigorios. They were taken to the prison beside the city hospital and tortured. On 3 October 1922, the clergy were taken outside of the town to be killed. According to witnesses, Metropolitan Gregory died of a heart attack before when the Turkish troops attempted to bury him alive.

A significant part of the local males was seized by the Turkish Army and died during death marches in the interior of Anatolia.

The French author René Puaux estimated the number of Greeks deported into the interior of Anatolia in late 1922 as high as 150,000.[21] Most of these captives were massacred outside Smyrna or other Greek towns of Ionia/West Anatolia. The remainder was kept in a state of slavery[22] and treated with genocidal intent. One survivor, the writer Elias Venezis (born Mellos; 1904-1973) wrote down his experience and memories as early as 1924, soon after the massive Greek-Turkish exchange of populations. A Greek youth of just 18 years from Ayvalık, Venezis was conscripted into a slave labour battalion and “remained a slave without any rights and even without any official recognition of existence for fourteen months”.[23] In his memoirs, Venezis tells how the Ayvalık conscripts were kept in the local prison several nights, during which 15 were selected to march outside the town to be bayoneted to death, while the remaining 43 were marched to the various labour camps of Western Anatolia. His group was the fourth such recruited group from Ayvalık, but in difference to the first three groups, numbering in hundreds his was determined to die in a slower way.[24]

After various death marches since 1915, disguised as deportations and after the previous conscriptions of 1914 and 1921 Turkish militaries and paramilitaries had achieved a rich experience in ways of physical destruction by indirect ways. Despite the time of the year and the already cold nights – it was the end of October 1922 – the Ayvalık conscripts had to undress with the exception of their underwear, and were marched in this semi-denuded state and without proper footwear to the town of Manisa (Magnesia, Magnisa). En route, they were not allowed to drink anything else but infectious swamp-water, with the clear calculation that typhus and other epidemics would decimate the undernourished, exhausted men. Deliberately they were kept under catastrophic conditions of lacking hygiene.

One of the first tasks of E. Venezis’ taburu in Manisa was to clear the area of the corpses of 40,000 Christian men, women and children from Manisa and Smyrna, which had been tied to one another with wire, before they were killed and dumped in a huge ravine of Mount Sipylos (Kirtikdere). The corpses already had begun to disintegrate, and the water drove them to the ravine’s edge, “where they reached the road and railroad tracks”[25]. The Turkish authorities feared that the floating remnants of massive killings of Christians might be seen by the Spanish official Dellara, who was “appointed to examine the conditions of the prisoners and the ‘care’ that the Turkish government was providing them.”[26]

Under such fatal conditions, the mortality rate of the Greek slave labourers from Western Anatolia was extremely high. Out of the roughly 3,000 male labour conscripts from Ayvalık, only 23 survived – less than one percent![27]