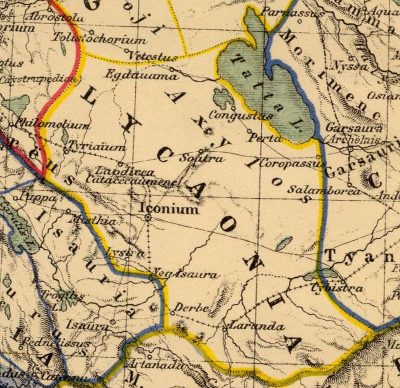

City of Konya / Iconium

The city’s industries include food, leather, textiles, cement, and carpetweaving. It is the trade center of a rich agricultural and livestock-raising area (wheat, barley, sugarbeets, sheep, Angora goats) and has trade in grain and wool. Mercury and magnesite are mined in the region. Manufactures include cement, carpets, and leather, cotton, and silk goods.

Population

In 1890, out of a total of 44,000 residents of Konya 3,000 were Armenians. They maintained two schools for 130 boys and 60 girls. (1)

History

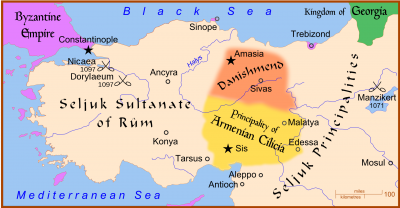

Iconium was part of the Roman Empire from the first century B.C. to the third century A.D., and later part of Byzantium. From the eighth to the tenth centuries, it was subject to invasions by the Arabs. It reached its peak after the victory (1071) of Alp Arslan over the Byzantines at Man(t)zikert, which resulted in the establishment (1099) of the Sultanate of Iconium or Rum (so called after Rome), a powerful state of the Seljuk Turks. In the late 13th century, the Seljuks of Iconium were defeated by the Mongols, and their territories subsequently passed to Karamania (see Karaman). In the 15th century the whole region was annexed to the Ottoman Empire by Sultan Mehmet II, the conqueror of Constantinople.

Konya lost its political importance but remained a religious center as the chief seat of the Mawlawiyya (Mevlevi) Sufi order (dervishes), which was founded there in the 13th century by the poet and mystic Jalal ad-Din Rumi. His tomb, several medieval mosques, and the old city walls have been preserved, and Rumi is honored in an annual festival.

In 1832 an Egyptian army under Ibrahim Pasha routed the Turks at Konya.

Destruction

The city’s Armenian population of 4,440 was largely deported during World War I.

“Since 6 August 1914, the vali, Azmi Bey, formerly prefect of police in Istanbul, had been mistreating the Armenian population of the vilayet and had extorted large sums from it ‘for the war effort’. In early May 1915, he organized house searches that went on for several nights, especially in the Armenian schools and homes of

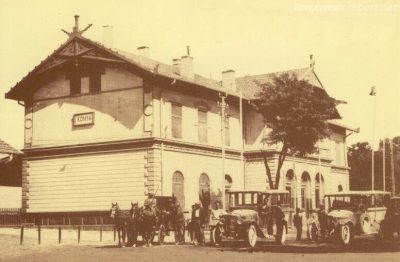

notables. Officially, the purpose of these operations was to locate illegally held weapons. In reality, Azmi’s instructions were probably to work up a compromising case against the Armenians in order to justify arresting the Armenian elite here as well. On the basis of a list apparently compiled earlier by the local Ittihadist club, 110 merchants, financiers, and elementary schoolteachers were summoned to the police station, then taken to the train station and sent off toward Sultaniye, east of Konya. In the same period, 4,000 Armenians deportees from Zeitun arrived in Konya in a pitiable state, after having trekked through Tarsus and Bozanti with no means of subsistence whatsoever.”[2]

Celal Bey, the “new governor was a well-meaning man who refused to deport the Armenians of his province. It was while he was absent – he left for ‘medical care’ in Istanbul – that the first convoys of deportees from Adabazar arrived in Konya, around 15 August, after being pillaged on the way. (…) Taking advantage of the fact that Celal was in Istanbul, the local Young Turks hastened to put nearly 3,000 Armenians from Konya on the road on 21 August. (…)

In the few days that preceded the departure of the first convoy from Konya, the city was transformed into a marketplace. Improvised sales took place everywhere. Often, the city’s Turkish inhabitants went to inspect the Armenians’ houses and suggested that their owners give them their belongings, for which they would have no further use, ‘since [they] would be left alive, at best, only a few more days.’ Archbishop Khachadurian, accompanied by the Reverend Hampartsum Ashjian, sought in vain to bring the commanding officer of the German contingent stationed in Konya to step in. Even the American missionaries could only stand by helplessly and watch as the Armenian presence in Konya was wiped out. The committee responsible for ‘abandoned property’ laid hands on the deportees’ houses and arranged the transfer of bank accounts and the precious objects they had deposited with the banks before going to watch the demolition of the Armenian cathedral ordered by a çete leader, Muammer.

A second convoy, comprising the last 300 Armenian families from Konya, had been assembled at the railway station and was ready to set out when the vali, Cemal, returned from Istanbul around 23 August. Saved by his intervention, these families were given permission to return to their homes, which had already been stripped of a good deal of their furniture. For as long as Cemal held his post – that is, until early October – these people remained in Konya and, side-by-side with the American missionaries, rendered great service to the tens of thousands of Armenians from the western provinces who passed by way of Konya’s train station. As soon as the vali was transferred elsewhere, they were deported in turn, on the initiative of the CUP’s responsible secretary, Ferid Bey. It is, however, noteworthy that the lists of people to be exiled were regularly drawn up beforehand and Celal was unable to prevent them from being deported.” [3]

Persecution and deportation of Greek Orthodox Christians

According to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, persecution and discrimination against Greek Orthodox Christians began in Konya even before the First World War. There were numerous arrests there just because a child wore Greek letters on his cap.[4]

During and after World War I, Konya province was a deportation area for Greek Orthodox and Armenian Christians from other regions as well as an area whose Christian population was deported.

In his statement of October 1917, the chairman of the Greek Relief Committee, Frank W. Jackson, mentioned the deportation of “most of the Greeks of the Marmora regions and Thrace (…) the pretext that they gave information to the enemy. Along the Aegean Coast Aivalik stands out as the worst sufferer. According to one report some 70,000 Greeks there have been deported toward Koria [Konya] and beyond. At least 7,000 have been slaughtered. The Greek Bishop of Aivalik committed suicide in despair.”[5]

The Swiss doctor’s assistant Jakob Künzler, who witnessed the plight of the Pontian Greeks, recorded the last impressions of the days he spent in Turkey:

“At that time, the Turkish governmental council decided to deport, among others, the Greek Orthodox population of the country. This resulted in the transfer of unending human columns from Merzifon, Sivas, and Konya to Harput, Diyarbakir and Bitlis. It was in the heart of winter. Approximately 90% of the deportees died during the journey. While crossing the Taurus Mountains on my first journey to Harput, I encountered the bleached bones of thousands of these victims. The Near East Relief organization, which was active in the country, would gather abandoned children, many of whom were kept in Malatya. This was where I had to go to pick up those children, of whom there were 900. The American who was taking care of these children could only provide them with food and shelter in a rented house. He was not allowed to tend to their other needs. At that time, the area of Malatya was suffering from an outbreak of malaria.

Several children died daily. Within a week, while I was still there, 20 of these poor souls died. I wondered how I could transport such a crowd of children.

The government, who—oddly enough—was not at all friendly towards me, initially demanded that I give them a list with the names of the children who were to leave. In accordance with their health condition, I separated the children into three groups: the healthier ones would cross the mountains to the South on mules, while I hoped to transport the weaker children in the second group with carriages through Diyarbakir. Finally, those who were very ill, I would transport by car.”[6]

In his report of 7 March 1917, the Hellenic consul of Konya (Grk.: Iconion) described the situation of the Greek Orthodox forced laborers at a time, when Greece was still neutral:

“These unfortunate men, on being drafted into these battalions, are distributed throughout the interior of the Empire, from the coasts of Asia Minor and the Black Sea to Bagdad, the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, and Egypt, some to construct military roads, others to make tunnels for the Bagdad Railroad, and others to cultivate the fields. Receiving absolutely no pay, badly nourished and clothed, exposed to changes in the weather, to the blazing sun of Bagdad and the intolerable cold of the Caucasus, assailed by sickness, fever, eruptive typhoid, and cholera, they are perishing by thousands. For a while those able to pay the exemption fees were released from service; and thus those who were relatively well off were rescued from ruin and sure death, but for the last five months these, too, have been compelled to serve in these labour battalions. While visiting the hospitals of the city of Iconium, I have seen these unfortunates stretched out on their beds or on the ground like living skeletons, waiting in agony for death as their deliverer from this life of misery and privation. There is a total lack of drugs and food, and the only attention any sick receive is a visit from the doctor twice a day. Those who are able to stand go about the streets of the city begging a piece of bread. In order to give a faithful picture of this grievous situation it is enough to state that the cemetery of Iconium, as a result of the great mortality of the Greeks working in these labour battalions, has been filled to overflowing with graves in which not one corpse, as is the usual custom, is buried, but into which are cast, like dogs, as many as four, five, or even six dead.

As for the ‘deserters’, they were not only treated with the harshest cruelty, but their alleged existence in a given village was often the excuse for tortures of the other inhabitants to make them disclose their whereabouts, accompanied by confiscation, plundering, massacre, and other excesses.”[7]

Greek Orthodox Church of Amphilocos, destroyed by the Turks in 1916. (Source: The New Near East, November 1920., p. 13; https://www.greek-genocide.net/images/Photos/Photos/Amphilocius_Konia.jpg)

Deportations 1921-22

Dr. Mark H. Ward, a physician working for the U.S.-based Near East Relief, observed how a total of 828 Greeks as well as 810 Armenians were deported from Konya to Elazığ from May 26 to July 19, 1921.[8]

Survivor Marianthi Karamousa from Bağarası (Gr: Μπαγάρασι), a village located 14 km SE of Söke and 30 km SW of Aydin, was deported 600 km inland in autumn 1922, first to Konya, then to Niğde. She recalled:

“’We walked all day and sometimes night too. They wanted us to die. Women, young children; walking and walking. Whoever couldn’t walk anymore was left on the side of the road. The first to fall from exhaustion was Barba Konstantis the candle lighter at our church. He laid lifeless under some branches. Nobody buried him, no one blessed his body. One by one they dropped. We passed Nazilli, Denizli, Dinar, the others I don’t recall. At each stop there was a change of gendarmes [policemen]. Finally, we arrived at Konya. I don’t recall exactly how long it took, but I think it was two months.’”

Three of Marianthi’s children died of food poisoning after eating contaminated meat during the deportation. Her mother also died en route. A deportee alerted Marianthi that the gendarmes were about to ‘get rid’ of her mother. Marianthi ran to where they had her mother but was pushed away by the other gendarmes. From a distance, she witnessed her exhausted mother – who could barely stand on her own feet – being held up by the gendarmes. They were removing all her clothes one by one until she was naked, shaking each item in the hope something of value would fall out.

During the deportation, they encountered Greek captives who were wandering the countryside, starved and homeless. These Greek captives were given long sticks by the gendarmes and were told to beat the deportees with them. The ends of the sticks had darkened from the amount of blood they had drawn from the beatings. This was the ultimate insult. The Turks were using Greeks to beat the Greek deportees. As Marianthi recounts:

‘A Christian beating a Christian. This is what the dogs (the Turks) were doing to us! We weren’t human. We were nothing (to them).’

Marianthi’s mother died from the beating she received from one of these Greek captives.

Diseased, flea ridden and starving, they arrived at Konya and were driven on to Nigde (250km from Konya) where they were put into a barn used to house animals. Marianthi recounts:

‘We were driven further again until we reached a place just out of Nigde where they put us into a barn where animals are kept. ‘Keratalar giaour’ (bloody infidels) they would shout at us as they dragged us along. They threw us in and left us there. We were in terrible condition. Our clothes were soaking wet from all the rain, we were covered in fleas, diseased and were running a fever and hungry. Another three of my children died here. I left Bağarası with 9 children and only 3 survived.’

At a place called Fertek, just outside of Nigde the deportees were helped by Turkish speaking Christians who housed and fed them after seeing the state they were in. Marianthi and her 3 children eventually made their way to Mersin and finally boarded a ship to Greece.” [9]