Situated south of Lake Van and in the south-eastern part of the Bitlis province, the administrative center of Hizan is located 35 km southeast of the provincial capital Bitlis. The Hizan River, a tributary of the Eastern Tigris, flowed through the kaza. The northern-southern parts are mountainous, while the southern-western parts are plain. The soil in the plains was fertile. Subsequently, Hizan was rich in fertile agricultural fields. Armenians cultivated grain crops there (wheat, barley, millet), grapes, cotton, and fruit trees (chestnut, oak, etc.). The region has rich vegetation and forests, full of wild beasts.

There were silver, copper, lead, iron and other mines in the kaza. The main occupation of the Armenian and Kurdish population in the south-eastern mountainous region of the kaza was field work (cultivation of grain, grapes, cotton and tobacco).

Toponym

The name of the town and kaza of Hizan (Armenian: Խիզան; previously: Erzent) seems to be connected with the place name Kirza mentioned in Assyrian inscriptions. According to the Armenian scholar Gh. Inchichyan, the name originated from Persian word ‘sehetkhizan’ (‘hanging’).

Administration

Under Ottoman rule Hizan belonged to the Eyalet of Van, forming the domain of the Kurdish family of Sherefs. After 1896, the kaza of Hizan was included in the Ahlat sancak of the Van vilayet. Ecclestically, Hizan belonged to the Catholicate of Akhtamar. In 1910, Hizan village was the seat of an Armenian Apostolic bishop of the Akhtamar Catholicate with 69 parishes, 64 churches and 25,000 believers.

Population

The number of the Armenian population significantly decreased in the 16-17th centuries, due to the devastatingly long Ottoman-Iranian wars and the invasion of Kurdish tribes. But until the 1870s, Armenians still formed the majority there. However, as a result of the Russian-Ottoman war of 1877/8 and the subsequent famine, the number of Armenians decreased sharply. Many Armenian families left the province in the 1880s. In 1891 the kaza of Hizan had 27,070 inhabitants, most of them Armenians and Kurds. In 1895 the kaza of Hizan counted dozens of Armenian villages. According to Catholicos Khachatur III (d. 1895) of Akhtamar, in 1895 Muslims killed 400 Armenians in 40 villages of the county, destroying Armenian churches and monasteries. In 1909 there were still 23 Armenian-populated villages with 489 houses. 30 percent of the kaza’s overall population were Christians.

Most of the remaining Armenian population was massacred during 1915. All the others were deported.

There were a number of centers of Armenian writing and culture in Hizan, among them Surb Khach (Holy Cross), Baredzor (Seven Tabernacles), and Surb Gamaliel monasteries. According to the Mshak newspaper of 1881, the kaza had 11 monasteries, 70 churches and 3 colleges.

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century the kaza of Hizan was divided into three municipalities (nahiye), which together had 168 villages, 68 of which were inhabited by Armenians, with 23 villages in the vicinity of Hizan, 16 in Mamrtank, and 29 in Sparkert (Western Armenian: Spargerd). “Hizan counted at least 75 Christian villages, all Armenian, although some of them, particularly in the northern and north-western part of the district, also had a Kurdish population.”[1] According to the census of the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople, at the eve of the First World War there lived 8,207 Armenians in 76 localities of the kaza Hizan, maintaining 48 churches, ten monasteries and 14 schools for 500 students.[2]

“According to the Ottoman government in 1914, Hizan had a population of about 70% Muslims and 30% Armenians. Given the high number of Armenian settlements in Hizan, this looks like an undercount, and in view of the sizeable emigration before 1895,20 the actual proportion may well have been 50% or higher. Mixed Christian-Muslim villages were rare in Şirvan, but more numerous in Hizan.”[3]

The following village groups (nahiye) with Armenian populated villages were included in Hizan kaza:

Աղյան – Aghyan (3 houses); Անապատ – Anapat (22 houses); Անտյանց – Antyants (42); Դարոնց – Daronts (38); Խածուս – Khatsus (12); Խարխոց – Kharkhots (24); Խարկե – Kharke (36); Խուփ – Khup (9); Կապան – Kapan; Կատինոք – Katinok (18); Կարասու Վերին – Karasu Verin (25); Կարասու Ներքին – Karasu Nerkin (18); Հեղին – Heghin(21); Ճում – Chum; Մահմըտենք – Mahmetenk (30); Մանտենց – Matnents [also: Mamedank, Mamerdan/Nimran, Mamırdunk] (22); Նամ – Nam (9); Նորաշեն – Norashen (10); Շեն – Chen (18); Պախոր – Pakhor (17); Պռոշենց – Proshents(15); Պրյունս – Pryuns (34); Ս. Խաչ գյուղ – Surb Khach gyur(20); Տի – Ti (38); Փալսատ – Palsat (8)

Verheij Jelle: Kurdification of the kazas Hizan and Şirvan as a result of the 1895 massacres of Christians

“While a large part of the Kurdish Muslim population was sedentary and the villages in the area inhabited yearlong, Şirvan and Hizan were also both ‘home’ to a number of nomadic Kurdish tribes, which used the high mountain meadows in the summer and wintered in lower regions outside the districts. Both Hizan and Şirvan suffered a lot from the Ottoman centralization in the 1830s and 1840s, when local Kurdish overlords (bey-s or mir-s) were driven out and replaced by direct Ottoman administration. In the Hizan area, there were two dynasties of beys, those of Hizan and those of Sparkert/İspayirt, both probably already weak and largely defunct at the beginning of the 19th century. (…) The new Ottoman administration was largely nominal, however, and in Hizan and Şirvan, even late into the 19th century, there were just a few officials headed by a kaymakam (district governor), with few troops or police at their disposal and barely able to enforce the law.

(…) In Hizan, these sheikhs had their center in Gayda, close to the district’s administrative center, Karasu, and strongly influenced politics even in the provincial capital Bitlis until well after WWI. (…)

After the sheikhs, the second group to gain ascendancy following the centralization were the Kurdish (semi-)nomadic tribes. These were the nightmare of the sedentary population, due to their constant demands and exactions. The tribes in Hizan and Şirvan were typically small, although some of the larger tribes from elsewhere passed through the area seasonally.

Thus, the Ottoman centralization essentially created a power vacuum in the region, one that was partly filled by the Nakşibendi sheikhs and rendered it vulnerable to the Kurdish tribes. This may be characterized as a period of turmoil, therefore, only exacerbated by Tanzimat legislation, like the Land Code of 1858, which opened the way for a land grab. All formal and informal power remained in the hands of Muslims, however. The Christian population, both Armenian and Syriac-Orthodox/ Assyrian, had no administrative role, except for a quite meaningless representation (some notables placed in the local administrative councils created by the Ottoman bureaucratic reform). So, it was against this background of uncertain authority and shifting power that the Ottoman-Russian wars of 1853-1856 and 1877-1878 were fought, which fueled a generalized hatred of Christians among the Muslim population(s). Both Hizan and Şirvan were mountainous districts, with numerous valleys and some plains separated by mountain ranges, forming isolated micro-worlds that differed in terms of culture and the character of their peoples. They were not arid districts, and some parts were quite wooded. Due to its lower altitude and hotter climate throughout the year, the south of Şirvan, in particular, was known for its horticulture and high-quality fruit. Sedentary peasants practiced agriculture, horticulture and husbandry. Christians (Armenians and Assyrians) also engaged in cloth production, and in some villages, every household had a loom. Their customers were primarily their Kurdish neighbors, who in this respect were thus dependent on the Christians. (…)

Although there were several medieval Armenian monasteries in Hizan, testifying to a richer Armenian past, by the 19th century, Hizan and Şirvan were relatively underdeveloped districts. Thus, while the Armenian Church and societies dedicated to the development of education elsewhere had a large network of village schools, in Hizan, only around 10% of the Armenian villages were reported as having schools, and in Şirvan they were virtually non-existent. (…)

The people of Hizan and Şirvan did have a lot of contact with the outside world, however, since many Kurdish and Christian men worked seasonally in Constantinople. This may have been one of the reasons for the support among peasants of the Armenian revolutionary movement – in which respect the proximity of Van, an important center of Armenian political activism, may have been crucial. Support for the revolutionary movement generally seems to have been more widespread in Hizan, particularly in Spargert [Sparkert]/İspayirt, than in Şirvan. (…)

The chaotic situation of the 19th century took a heavy toll on the sedentary population in the area. State authorities collected revenues through an oppressive tax-farming system, while the nomads frequented villages with their own incessant demands, including for unofficial ‘taxes.’ The sheikhs were active as tax-farmers and money-lenders, not hesitating to demand excessive interest rates or forced labor. (…)

Although the peasantry in general suffered, Christians were subject to further exactions. To the state they paid an extra tax for exemption of military service, those engaged in textile production also paid the special temettü [dividend] tax. Moreover, the sheikhs seem to have specifically targeted non-Muslims. The Hizan sheikhs, who were known for their religious fanaticism and hatred of Christians, exerted a localized reign of terror. As a consequence of oppression and economic hardship, many peasants sought employment elsewhere, by seasonally migrating, or fleeing the land forever. By all accounts, migration was already extensive before the 1880s. Locals told travelers stories of a glorious past when the villages were much larger and prosperous. In the two decades before 1878, the Armenian rural population of Hizan was said to have declined by 80%. Since none of the regional capitals – Diyarbekir, Bitlis or Van – showed any remarkable population growth during the 19th century, presumably the final destinations of the migrants were faraway places where many other Armenian emigrants went too, like Russian Armenia, other territories of the Russian Empire or Constantinople. Although it is impossible to ascertain the extent to which Kurdish peasants from Hizan and Şirvan also left their land, we may assume that the majority of the emigrants were Christian. Hence the Kurdish population percentage increased after the centralization. A gradual process of Kurdification was also observed in nearby districts in the province of Van.

(…)

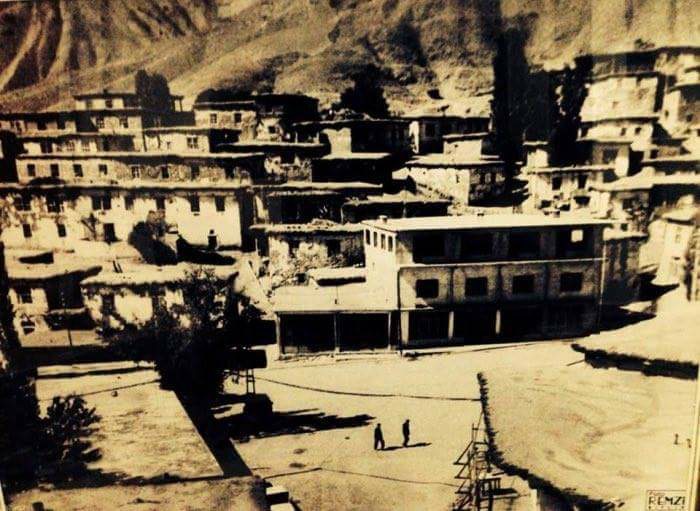

Hizan central sub-district

[British ]Vice-consul Crow counted six Armenian villages here. They were attacked and plundered by Kurds from the area, and, according to Crow, 15 Armenians killed. This was the heartland of the sheikhs of Hizan. Under their pressure the Armenians converted to Islam, but with few exceptions reconverted a year later. Forty families fled the district. Crow highlights the unbearable oppression of the remaining Armenian villagers by the sheikhs after 1895.

The lower Gargar Valley (north-eastern Hizan)

In this district of 10-11 Armenian villages, according to the report of the Catholicos of Akhtamar, some 65 people were killed. (…) The attackers seem to have been Kurds from the Aliganli tribe. All surviving Armenians converted to Islam on the instigation of a local agha, a supporter of the sheikhs.

Shenadzor (eastern Hizan)

According to the Catholicos, some 400 Armenians were killed here and in the central district of Hizan. In contrast to his data on other districts, no specification per village was offered, suggesting this was an estimate. Crow mentions 17 dead in this district. There was considerable plundering. The main perpetrators were again the Aliganli, who also attacked local sedentary Kurds. Followers of the sheikhs prevented further bloodshed on condition that the Armenians converted to Islam. When Crow visited the villages in 1897, he found local Kurdish guards there, and that the Armenians spoke “well of their Kurdish neighbours.”

Sparkert/İspayirt

The Catholicos mentions 300 dead in the 28 villages of the district, based on a count per village. Curiously, following his visit to the district, Crow concluded that it “seems to have suffered less during the disturbances of 1895 than any other part of the Vilayet of Bitlis.” He claims that 11 of the 25 villages converted to Islam, “while the rest were unmolested, and the proportion plundered [did] not exceed two or three.” Crow thought this was due to fatigue of the attackers. He noted however that the villages that were attacked suffered considerably, citing two instances, where a total of 25 people were killed.

Mamerdank [also: Mamedank, Mamerdan/Nimran, Mamırdunk] (southeast Hizan)

[British Vice-consul] Crow counted 12 Armenian villages in this district, the Catholicos 17. According to the latter, 160 Armenians were killed, while Crow gives a total number of 30, which seems too low since he mentions 26 victims in two villages only. More than 60% of the Armenians (100 of 163 families) fled the district, and at least one village, on the plain of Ov, was deserted forever. Crow described in detail the fate of the famous monastery of the Holy Cross of Aparank in Mamedank, close to the border of Hizan with Pervari. Due to the unsafe situation, the abbot had already left six years before, and a caretaker looked after the monastery. In 1895, Dahar Agha of the Aliganli, “described by the Kurds themselves as being the highest brigand of the neighbourhood,” took up his quarters in the monastery, compelled the caretaker and his family to convert to Islam and occupied both the monastery and the lands. When Crow visited the monastery two years later, he found it to be occupied by “Kurdish families” and the converted caretaker: The church and its precincts are turned into a barn for the storage of Dahar Agha’s hay and grain, and the altars used as dressers for the accommodation of cooking pots and culinary utensils. The floor of the chancel and the nave are covered with heaps of wheat and barley, and the side aisles blocked with stacks of hay. The vestments, vessels, and other accessories have been appropriated by the Kurds, and the sacred books and archives partly destroyed, and the remainder given to the Kurdish children to play with. Aparank was not the only monastery in the area permanently abandoned in 1895. The year was the death blow to a number of monastic establishments that had historically been at the center of Armenian cultural and religious life.

(…)

Conversion to Islam

The events in Şirvan and Hizan attracted wide attention for their large scale of conversions to Islam. Indeed, all consulted sources confirm that almost all Armenians and Assyrians, some several thousand people, converted. The main reason for this was the fear of further violence and a hope for survival. Often it seems, conversion was an option not offered by the attackers but by Muslim neighbors, who either thought that the conversion of the Armenians was necessary for religious reasons or saw this as a practical method to avert further attacks by the tribes. In Hizan, the sheikhs were prime movers. Since they had previously been instrumental in cases of conversion, they seem to have had a vision of Islamization for their territory. The sheikhs look like the most important single factor in the mass conversions. One of the most interesting finds of this research is that the large majority of the converts, away from public attention, reconverted within a few years. For some, this reconversion could only take place away from their oppressors, having fled their homes. In Hizan, only a small majority of the Armenians remained Muslim.

(…)

The reconversion of so many people was, in principle, tricky, since in Muslim doctrine apostasy is punishable by death. Church authorities were of course against the conversions and, within their limited possibilities, struggled to regain their flock. An important factor was the position of Ottoman authorities, which did not accept the conversions. Diplomatic reports show that the Sultan himself was strongly opposed to conversion of non-Muslims in general, particularly if just for practical reasons. The same mentality existed everywhere in the bureaucracy. The anti-conversion stance that the Ottoman authorities had regarding Hizan and Şirvan fits in with the pattern identified by Selim Deringil in his research on the mass conversions of 1895.[4] Interestingly, one of the arguments mostly used by the officials was that mass conversions would offer the foreign powers reason to criticize the Empire. Fear for loss of possible revenue (in particular the exemption tax for military service Christians made), seems to have played a role as well. Some local Muslims seem to have taken a similar position. Still, it is quite possible that some families who converted in 1895 never reconverted and stayed Muslim. And it is likely that they continued with their Christian beliefs and practices at home, thus falling in the category of ‘crypto Christians,’ still extant in various regions of Turkey. In both Hizan and Şirvan, villagers may still occasionally be encountered who are identified as ‘Christians’ by the local population, even though they are officially Muslims. Given the extreme restrictions on conversion to Islam during WWI, these people are more likely to be the descendants of converts from 1895, who thus survived 1915.

Aftermath

(…) the attacks of 1895 were a terrible and traumatic blow to the Christian population of the districts. The British consuls who visited Hizan and Şirvan reported numerous instances of the terrible plight of the villagers after the massacres. The most important reason was the systematic and thorough plunder to which they were subjected. Having lost almost all their goods and animals, it became impossible to produce. Hunger and inability to pay taxes were the terrible results. Forced to lend money from rich Muslims, usually sheikhs and aghas, sometimes the very same people who had attacked them in 1895, the poor villagers accumulated debts that they could never pay back and started to lose their lands to their creditors. Security measures introduced by the authorities, such as a ban on seasonal migration (for Christians and Muslims alike), only worsened the situation. Moreover, all the oppression that was already apparent before 1895 seriously worsened. Those who reconverted were particularly at risk. It was reported from Hizan that ‘the more fanatical’ Kurds despised those who reconverted. Fear of violent reactions from neighbors kept many from reconversion.

The combined result of hunger, economic hardship and oppression was land flight. In and after 1895, high numbers of Christians in Hizan and Şirvan fled their lands. From 22 villages in Şirvan more than 50% of the population left. A systematic count for Hizan is lacking, but contemporaneous sources confirm that emigration from here also took place. That some 100 people from Hizan were said to have perished in the conflict in Van in 1896, gives some indication of the number of refugees. Monahan concluded his report as follows:

The Christian villages having gone through massacre and plundering are now being ruined beyond hope of recovery by the extortionate and conscious practices of the financing Sheikhs, Beys and Aghas into whose hands the money lending business which was once Armenian, has now passed. Much land has been thrown out of cultivation and abandoned, much has passed into the hands of the Kurds. Whether the strengthening of the latter element will prove to mean the ruin of the country and the Government remains to be seen.

Two decades before the almost complete elimination of the Christians, the 1895 massacres constituted an important, yet unrecognized phase in the Kurdification of the districts of Şirvan and Hizan.”

Excerpted from: Verheij, Jelle: “The year of the firman:” The 1895 massacres in Hizan and Şirvan (Bitlis vilayet). “Études Arméniennes Contemporaines“, Dec 2017, 10(10), pp. 129-152