Toponym

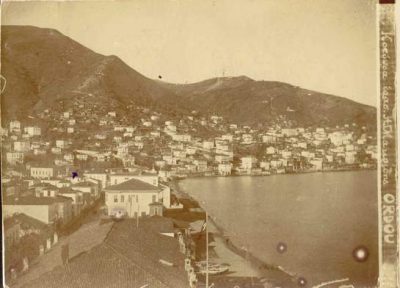

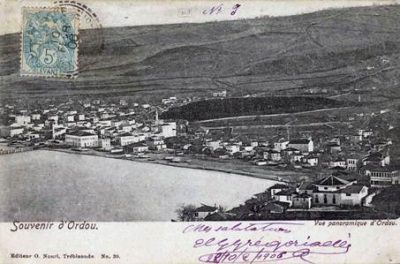

The port city, after which the Ottoman administrative unit got its name, was founded as Kotyora (also Cotyora) by the Miletians as one of a string of colonies along the Black Sea coast. According to Diodorus Siculus it was a colony of the Sinopians. Suda mentioned that it was also called Cytora (Κύτωρα). In 1869, under Ottoman rule, the city’s name was changed to Ordu (‘army’; today: Altınordu).

History

Xenophon‘s Anabasis relates that the Ten Thousand rested there for 45 days before embarking for home. Strabo also mentions it. Under Pharnaces I of Pontos, Kotyora was united in a synoikismos with Cerasus (Kerasos, Giresun). Arrian, in the Periplus of the Euxine Sea (131 A.D.), describes it as a village “and not a large one.”

The area came under the control of the Danishmends, then the Seljuk Turks in 1214 and 1228, and the Hacıemiroğulları Beylik in 1346. Afterwards, it passed to the dominion of the Ottomans in 1461 along with the Empire of Trabzon.

The modern city was founded by the Ottomans as Bayramlı near Eskipazar as a military outpost 5 km west of Ordu.

Since the second half of the 19th century, Ordu is famous for hazelnuts, producing about 25 percent of the worldwide crop. As of 1920, Ordu was one of the few producers of white green beans, which were exported to Europe. Ordu also had mulberry tree plantations for sericulture.

On 4 April 1921, the current Ordu province was created by separating from Trebizond Vilayet.

Population

At the turn of the 20th century, the city was more than half Christian (Greek and Armenian), and was known for its Greek schools. According to a 1911 statistical survey on ‘Greek villages in Pontos’, there lived 39,800 Greek Orthodox Christians in the kaza Ordu, in 109 communities, with 100 schools, a monastery and 80 ‘private churches’. 103 other churches were Catholic.[1]

Armenian Population

“The Armenians of the kaza of Ordu, most of whom had roots in Hamşin, and whose ancestors had settled relatively late in this area, numbered around 13,565. Three thousand of the kaza’s Armenians resided in the principal town, also known as Ordu; the others lived scattered about 29 villages. The development of the seat of the kaza dates from the second half of the nineteenth century, when Armenians, who had come from Tamzara and Kirason [Giresun; Grk.: Kerasunta; Kerasus] settled in the quarter known as Boztepe. It was these Armenians, who introduced the cultivation of hazelnuts to the region, founded the city’s weekly market and developed limestone, silver and manganese mining and export. As for the 29 villages in the hinterland (located at least one hour and at most ten hours from Ordu), they were organized in six rural clusters to the south, southwest, and west of Ordu, notably in the valleys of the Melet Irmak and its tributaries (…).”[2]

The Destruction

During WW1: First Deportations from Ordu

June 1915: Deportation, Massacre and Drowning of the Armenians

“(…) Ordu was gradually isolated from the rest of the country in the first months of the war. The first arrests there took place around mid-June 1915. Five hundred regular soldiers took control of the Armenian neighborhoods and proceeded to arrest a number of men, who were then interned in the barracks jail. This operation lasted some six days: only after it was over was the decree ordering the deportation of the Armenian population toward Mosul made public. The first to leave were the men, who were tied together in groups of four, and led off in convoys of 80 to 100 people each. According to our witness [E.B. Andreasian], it was learned only much later that these men had had their throats slit in the woody valleys of the vicinity.

Certain prisoners succeeded, however, in gaining their release by means of bribes and thus were able to leave Ordu with their families in the convoys that were put on the road a few days later. The first caravan contained the families of the men who had been arrested and massacred. All these groups set out on the road that led by way of Mesudiye to Suşehir, which lay 30 kilometers to the west of Şabinkarahisar. Near Suşehir, in the nahie of Elbedir, many of these deportees were massacred and a large number of girls and women were abducted. A small group managed to continue its journey. (…)

The old, the sick, and the infirm, who had been briefly admitted to the hospital of Ordu, or other institutions, were shortly thereafter officially sent by boat to Samsun. In fact, they were drowned out at sea in conditions similar to those we observed in Trebizond. A group of women and, especially, children of both sexes between the ages of three and 12, went into hiding in the homes of Greek, Georgian, or Turkish friends; these people remained in Ordu after the convoys left. But the authorities’ threats apparently convinced their friends to get rid of them. In some cases, the authorities distributed these children to families in Kirason [Giresun] and in others took them out to sea and killed them. AT the fourteenth session of the trial of the criminals of Trebizond on 26 April 1919, Hüseyin Effendi, a merchant from Ordu, certified that Faik Bey, Ordu’s kaymakam, dispatched two barges loaded with Armenian women and children toward Samsun, which ‘came back empty two hours later’. These boats could not have made the journey to Samsun and back in so short a lapse of time; their passengers were, in other words, ‘lost at sea’. A few dozen adolescents nevertheless managed to flee to the nearby Pontic Mountains, where they survived for three years.

(…) It should finally be noted that after the Russians captured Trebizond, the innkeeper Niyazi was dispatched by [governor] Cemal Azmi to Ordu with the mission of deporting the Greeks and selling off their property ‘at ridiculously low prices’.”[3]

Deportations of the Greek Population

The Young Turks maintained the pretext of military justification even when the Ottoman Empire was winning. When the tide of battle changed, and the Ottomans reconquered the Trebizond vilayet, they continued expelling Greeks systematically. Greek witnesses alleged that Refet Pasha, the military governor of the Samsun sancak, burnt and depopulated dozens of villages between November 1916 and May 1917. During December 1916, the Turks deported notables from Samsun, Bafra, Ordu, Tirebolu, Amasya, and Çarşamba and apparently hanged 200 Greeks on charges of desertion. [4]

A documentation of the Ecumenical Patriarchate at Constantinople quotes ‘Deli’ (‘Crazy’) governor Refet (Raafet) with the following: “Deli Raafet Pasha, this murderer and incendiary of the district of Samsoun, during the persecution of the Greeks of Pontus, expressed himself in the sense that he will change the Greeks to become boatmen and porters (hamals); and in reality, after the people had plundered the property of the exiled Greeks, and burned their houses, the Turks who up to that moment were boatmen and hamals, became millionaires, whereas the Greeks who up to that moment were very well of and rich, died or nine tenths of them were killed in exile; and those who somehow have managed to return to their ‘houses, not only they do not find anything of their belongings, but they are swept off every day by hunger…‘”[5]

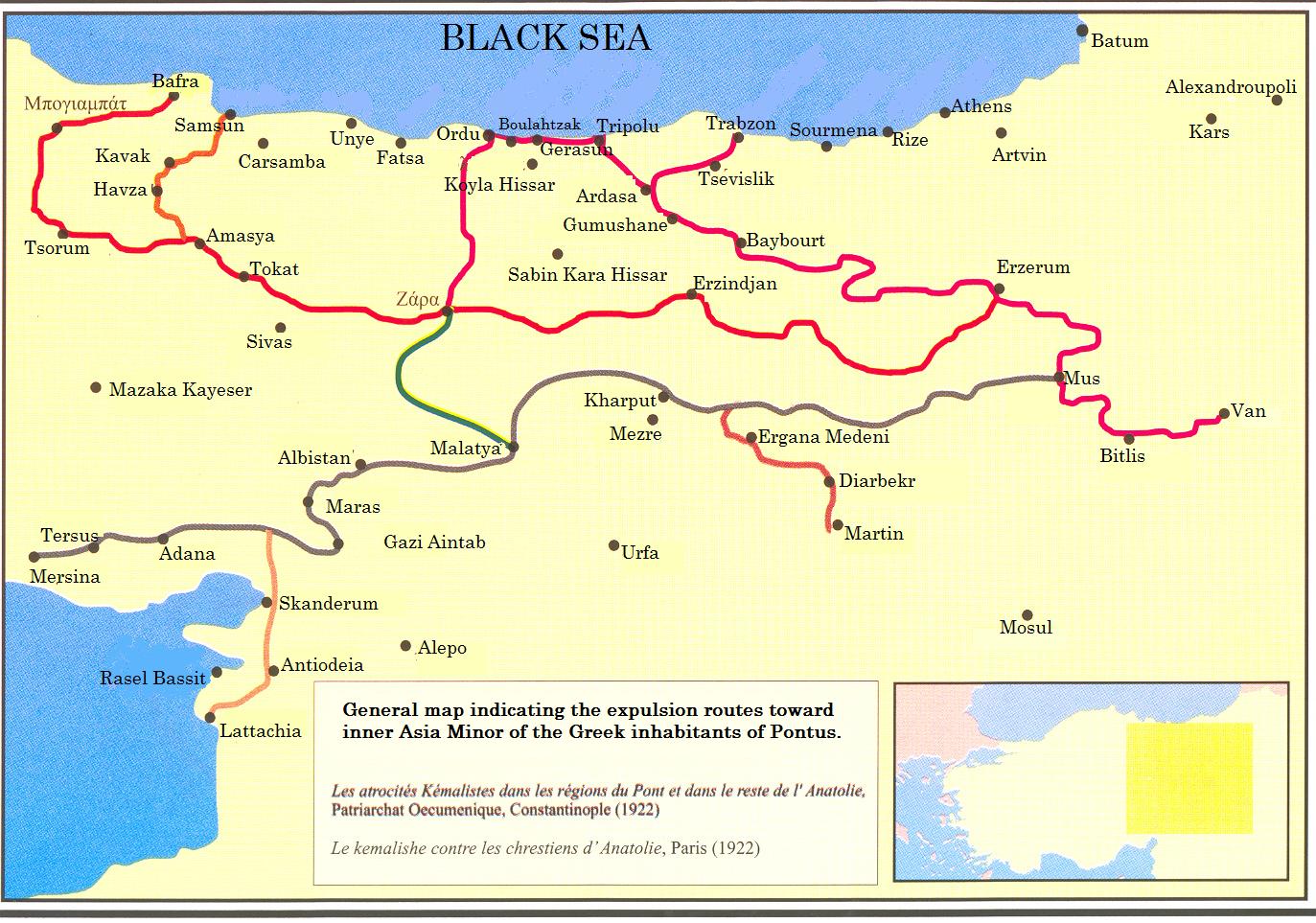

In 1916-1917, Greeks of the towns of Ordu, Ünye, and from parts of Giresun and the surrounding villages were deported to the interior of Asia Minor. After the destruction of the villages in the kazas of Tirebulu and Giresun (Tripolis and Kerasus), it was the turn of the Greek or mixed villages of the ecclesiastical district of Kotyora (Ordu), under the pretext of their proximity to the coast.[6] “The orders were plain and straightforward; the instructions of the administration explicitly entailed mass deportations in the middle of winter in order to achieve its ultimate goal.”[7]

“The bombardment of Ordu [Kotyora] by the Russian navy on August 11, 1917, inflicted damage on several Christian houses, especially in the Evangelist quarter, with its beautiful church and school, and consequently created a new wave of Greek refugees. Upon departure, the Russians were joined by numerous Greeks seeking to escape the vengeance of the Young Turks. Ten days after the Russian raid, the Turkish authorities decided to send the Greeks of Ordu to the interior of Anatolia for the second time, leaving them one week to prepare for the new journey. According to Lazaros Amanatidis, who was one of the displaced: ‘The Turks gave notice that the displacement of the Ordu Greeks would begin on September 1, 1917. All Greeks embarked upon a desperate effort to sell their belongings as soon as possible, in order to have money on them for the journey. Wool which had been bought unrefined for 60 piastres, was being sold refined for 5 piastres. A machine which had cost 10 gold liras was being sold for 5 paper liras.’

In refutation of the Young Turks’ claims regarding the alleged unreliability of the Ordu Greeks, Austrian consul Ernst von Kwiatkowski attributed their displacement to economic factors: ‘Indications of hostility towards the Greeks are on the rise; Greek negligence incites brutal retaliation on the part of the Turks. Because of their hatred, they will not even give them bread coupons’.”[8]

A memorandum of the Central Committee of the Provincial Associations of Pontian Greeks in Constantinople, addressed to the Paris Peace Conference, states with regard to the situation in the Ordu region:

“In August 1917 alone, 2,700 of the residents of Ordu were abducted by the Russian Army and taken to Russia. Of the 25,000 exiles, from the villages on the one hand, only 6 per cent of those from villages were saved from the catastrophe dealt by the satanic Turkish savagery, along with 35% from the towns. Twenty priests from the province were shot, hanged, burnt or buried alive. Ordu presented an image of unimagined destruction; 9/10 of Greek homes have been razed to the ground, while the plots are used by the Turks to plant cabbages.”[9]

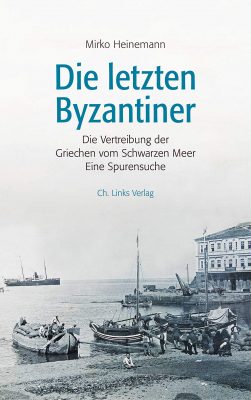

Mirko Heinemann: What is narrated about Ordu (9th August 1917)

“The summer of 1917 was no summer like any other in the town of Ordu on the coast of the Black Sea. The hottest days were gone, now the hazelnut harvest was about to begin. Every hand was needed. The fighting of the World War was not much noticeable in this remote coastal area. Only the young men were affected. They had to do military service. Therefore, it was mainly the women and children who cut the bushes and spread them on the ground to dry, while the grandparents did the household.

The migrant workers from Eastern Anatolia, who helped with the harvest every year, had not come that summer. So the Muslim Turks and the Christian Greeks had no choice but to do the work jointly. From morning to night they drudged on their home farm, and when the work was done, they went to the neighbors and helped out. When the church to the west of the city sounded the beat of the hour, the Christians paused for a moment and crossed themselves. When the muezzin called from the mosque in the east, it was prayer time for the Muslims.

In recent years the distrust between the ethnic groups had grown. (…)

The fate of the Armenians was only spoken about in a whisper. Two years had passed since the town crier had roamed the streets with his haunting chant, announcing the Ferman, the Sultan’s decree: All Armenians should sell their belongings and pack up what they could carry. Within days they would have to leave the place, after which they would be taken to a new settlement area. This resulted in an exodus of unprecedented proportions: in groups of several hundred people, they left with small carts or rucksacks, guarded by soldiers. Since those days in July 1915, the houses in the Armenian quarter of Ordu have been empty. Not even the children dared go near the empty buildings and the upper middle-class villas, whose doors creaked in the wind. And nobody dared to ask where the former neighbours had been taken.

Many Greeks retreated to their homes and prayed that they might be spared. Others shrugged their shoulders: That was just the war. (…)

Ordu lay in the east of the Ottoman Empire. Here one looked rather to Russia, whose glittering cities were only a few day trips away by steamship. The Orthodox Greeks regarded the likewise Orthodox Russians as their protective power. Many years ago, the Russians had even secured this status by contract. Moreover, many Greeks also lived in the Russian coastal cities. The trade relations were close. Many secretly hoped that the Russians would finally invade, take control of the Black Sea coast or return it to those who had always considered themselves the true masters of the area: the Greeks.

In the summer of 1917, that hope became tremendous. The Russian army was on the advance, already occupying Trebizond, where it had established a military base. It seemed only a matter of time before Ordu too came under Russian occupation. The Greeks prayed for it, their Muslim neighbours trembled at it.

On 9 August 1917, that day seemed to have come. It was already dark, the full moon stood over the city. Suddenly there was thunder. Fires broke out in some buildings down by the market. Thick smoke whirled through the narrow streets of the Greek Quarter, whose houses stood close to the hillside. Those who had a view of the sea saw a dozen warships spitting flames in the moonlight. Bullets hit the lower city, one also hit the Greek church. In the streets people ran together, screaming and crying. The ships had launched boats heading for the beach.

The warships came from Trebizond and they had hoisted the Russian flag. But they had not come to stay. It was a raid, a military raid. The Russian soldiers blew up an ammunition depot in Ordu and destroyed an airfield. When the Greeks realized that the Russians would disappear again, panic broke out. Shoutings rang out: “The Turks will take revenge on us. Leave your homes! Down to the harbor!”

Among the hundreds that rushed towards the Russian ships was a girl, 15 years old. An image had been etched in her memory that would haunt her for the rest of her life: how she put her slippers, which she wore in the house, by the front door. “We’ll be back soon,” her mother had comforted her. The two ran through the narrow streets of the Greek quarter down to the pier, where the crowd had gathered and poured onto the quays. They saw that foreign boats were docking there. In the middle of the turmoil, the mother’s hand slipped away from the child.

Calls ringing from somewhere: “Women and children first!” The people pushed the girl on until she was suddenly standing at the front of the gangplank. A Russian sailor lifted her down into the boat. Rigid with fright, she let it happen. Only when the boat cast off and the men steered it towards the ships with a strong stroke of the oars did she come to her senses. Above her, the stars swayed to the rhythm of the oars, and around her she heard the whining of other children and their mothers. Behind the smoke, the moon peeped out. It cast its pale light on an eerie scene: the shore was black with people, behind them houses were burning. The girl could not have known that this would be her last view on her hometown. She would never again see the house where she was born and raised.

So my mother would tell the story, which she in turn had heard from her mother. The 15-year-old girl who was separated from her mother on the way to the ship: That was Alexandra, my grandmother.“

Excerpted and translated from: Heinemann, Mirko: Die letzten Byzantiner: Die Vertreibung der Griechen vom Schwarzen Meer; eine Spurensuche. Berlin: Chr. Links, 2019, pp. 16-20

Further Reading: R. Lavinia Hanton: Remarkable Escape of Starving Exiles from Hands of Turks Brought to New York by Two of Those Saved. “The New York Times”, April 7, 1918

Ioakim Saltsis: Deportation of the Greeks from Kotyora to Erbaa, August 1917

“On August 11, 1917, the Greeks of Pontos were leaving on Russian warships. A total of about 3,500 of the Greeks of Kotyora found refuge at Trapezounta. About an equal number were left at Ordu to the discretion of the Turkish vengeance.

The next day, August 12, 1917, the rumors in the market place indicated that whoever was left would be exiled. This was the beginning of the plan of the local Turks, masters of Ordu and Vehip Pasha [Mehmet Vehib Kaçı], commander of the Turkish IV Army.

On the 4th day, the order from the prefecture about the exile was announced. The next day, the Greek community sent a telegram to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, in Constantinople, asking for intervention with the Ministry of Interior to cancel the order. Another telegram was sent to the commander of the IV Army, Vehip Pasha. All were in vain. The deadline for the beginning of the exile was only 8 days away.

The women and poor people started selling whatever they owned, clothing, furniture, utensils, anything they could get rid of. Their prices tended toward a ‘plate of lentils.’ And the Turks were purchasing…

Whole stores, fabric shops, grocery stores, and small family factories, with their appliances and tools, were sold at humiliating prices, 1/10 or even 1/20 of their value. The Greek property was transferred to the Turks.

The Greek population, more than 3,000, was divided into 7 groups according to an administrative plan. Every 2 to 3 days, a group would start out into exile.

The groups followed itineraries. Some followed the public road: Ordu, Merkez, Meseli Han, Martyros Han, Gölköy, Tarahta, Antuz, Lagosköy, Katran, Mesudiye (Melet). The rest went via Ordu, Kapatiz, Hangeri, Tsampasi, Mesudiye. This was the shortest route.

From Mesudiye, all the groups took the public road to Neocaesarea (Niksar): Mesudiye, Isketir, Senne, Paitarli, Perekketli, Pas Tsiflik, Neocaesarea, Erbaa, the last stop and place of exile.

The sufferings of the people were innumerable, due to the continuous marching. On the road, nightly rest, then on the road, always on the road.

The torture lasted 30 days for these people, carrying their mattresses and their small children. Most of them became sick from starvation and the rain. But they had to keep walking.

Deaths were not rare during the march. The poor creatures dug temporary graves with shovels they carried with them and buried the dead, and off they went. But Erbaa was to become the burial ground of the majority of ill-fated exiles. With the continuous walking, their health was tremendously weakened. The overcrowding in the town, the malnutrition and hunger in general, the incapacity to keep the principal rules of sanitation, brought typhus and dysentery. The disaster was serious. Forty per cent of the population was lost.”

Source: Saltsis, Ioakim: Chronika Kotyoron. Thessaloniki, 1955; English translation copied from the book The Greek Pontians of the Black Sea by the late Constantine Hionides, M. D.; https://hellenicresearchcenter.org/genocide-info/the-white-slaughter-at-kotyora-ordu/

1921-1922: Repeated Deportation of Returnees and Survivors; Atrocities

In Ordu the situation worsened day by day. Kara Hasan Yakub, Hafiz, Mecit, Fevzi, and others—irregulars of mostly Laz origin—looted Greek stores with impunity and abused Greeks. The commercial stores of the Makridis brothers were repeatedly plundered, due to their commercial success.[10]

On June 21, 1921, the Kemalists decided to deport the Greek population of Kotyora. Approximately eight hundred men and children, with a heavy escort of gendarmes, were taken to Mesudiye (Ordu district) without casualties, via the mule path from Kapatiz to Han Yeri and Çambaşı. Ioakeim Saltsis wrote: “In Mesudiye we remained in strict isolation for two days. This measure was taken by the kind commander of Şebinkarahisar to protect us from falling into the hands of Topal Osman and to gain time, until that brute and his ferocious band had moved away from the Commander’s territory.”[11]

“By August [1920] all the men in the Ordu region had been exiled. Ten villages, including Bey Alan, ‘bought off ‘ their harassers. But some of their men were later deported, and others fled to the hills.”[12]

“(…) on February 15, [1922] 200–300 brigands headed by Osman rode into Ordu, a village largely emptied of men but left ‘with a lot of Turkish [sic: Greek?] women.’ According to a survivor, Osman and his raiders had come ‘to carry off the plunder.’ The brigands torched all except two houses, into which about 170 women and children, and a handful of men, were herded. The houses were then set alight. Fifteen or so young girls were taken aside and ‘subjected to the most horrible treatment that night, and all butchered the next day.’ However, it was rumored that five or six girls were in fact spared ‘for the harem of the Pasha.’ Nine neighboring villages received the same treatment.”[13]

Cirillo Giovanni Zohrabian, a Catholic priest in Trebizond of Armenian origin and eyewitness to acts of violence against Christians in his district, concluded about Ordu: “Ordu had been an entirely Christian town; by order of Kemal, it was evacuated on December 29 [1922] and given to Circassian Muslim settlers from Russia.”[14]

Besides Ünye, Giresun, Samsun and other Black Sea ports, Ordu became an exit port for Pontic Greeks and Armenians exiled in 1922/3: “The degree of refugees’ suffering was determined to an extent by class. The poor reached exit ports—Giresun, Ordu, Ünye, and others—on foot. Those who could afford to came on freight trains or in carriages. From the trains they might be herded by stick-wielding soldiers to makeshift camps or directly to the harbor. On the steamers the moneyed minority enjoyed cabins, but most refugees languished on crowded decks. The conditions were often appalling.

One boat carrying 2,000 passengers from the Black Sea to Piraeus arrived with 1,600 cases of typhus, smallpox, and cholera. A U.S. Navy officer called it a ‘death ship’.”[15]

In March 1923 still ten-thousand awaited passage in Samsun, 3,000 in Trabzon, 1,500 in Ordu, 500 in Ünye, and 300 in Fatsa.[16]

Eliticide/Independence Courts

In 1920 the Kemalists arrested and exiled to Ankara Polycarpos, the Greek bishop of the “mixed town of Ordu”.[17] The following year, 1921, 190 “prominent Greeks” were reportedly hanged in Ordu.[18]

“It has been further ascertained by the correspondence of Samsun with the Central Committee that those imprisoned are fully active members of administrative and executive commissions in Trabzon, Giresun and Ordu. Of those imprisoned, the Independent Court of Amasya sentenced to death by hanging: Mattheos Kofidis, former member of parliament, member of the Central Committee of Pontos and political commissioner; Alexandros G. Akritidis, manufacturer of spirits; Nikos Kapetanidis, owner of the newspaper Epochi; Georgios Th. Kakoulidis, Giresun merchant; Spiros I. Sourmelis, secretary of the metropolitan; merchants Iordanis I. Sourmelis, Ioannis K. Atmazidis and Ioannis P. Spathopoulos; Avraam Tokatlidis and Epameinondas Grigoriadis, citizens of Ordu.

The following people were sentenced to death by hanging in absentia: (…) Ordu doctor Haralampos (…). The confiscation of the properties of those sentenced in absentia was also ordered.”[19]

February 12-16, 1922: Destruction of Greek Villages Above Ordu

“The following document was sent to State Department Near East expert Allen Dulles from Boston by Ernest W. Riggs, who may have known Dulles when both were working in Constantinople; Dulles was a diplomat under Admiral Bristol’s direction for a couple of years before reassignment to the State Department. The document originally came from Riggs’ brother, C.T. Riggs, a missionary in Anatolia, possibly on a visit to Constantinople.

The events described here occurred in a mountain village above the small port city of Ordu, which lies on the Pontic coast between Samsun and Trebizond. Savvas Yphantides, one of the fifty or so Greek men who hid in the forest and furtively looked on, describes the events, including his own wife’s death at the hands of the Turks.

The Riggs brothers were long-term missionaries of the American Board, and knew Yphantides’s family.

‘A trustworthy Greek of the village of Bey Alan, ten hours’ distant from Ordu in the mountains, arrived in Constantinople last week from Batum, after a most remarkable escape from his native place. He states that he was in Bey Alan from June 15, 1921, to March 18, 1922.

There were during the summer of 1921 five different orders for the deportation of Greeks from the Ordu region. In the first deportation, or sevkiat, all the men from 18 years to 50, almost 850 to 1000 in number, were exiled. Two or three weeks later came the order to send off those of from 50 to 60. A few were not sent for various reasons. In the fifth or last deportation were about 75 men, including all up to 60 years of age. By the end of August, 1921, all the Greek men of the Ordu region had been exiled; but Bey Alan, which was in the district [kaza] of Kerasoun [Trk.: Giresun], though really dependent on Ordu, bought itself off, as did nine other villages nearby. Many, however, of the men were sent off, and the rest, in fear of being likewise deported, hid in the mountains. In August came the order that all women and children from these villages go down to Ordu. By some means this order was countermanded and the women and children remained.

On January 25, 1922, it was rumored that Osman Agha, the famous chief of the chetes, or irregular bands, was coming to the region of Karasun and the Greeks realized that this boded no good for them. A few days later the Turkish villagers from nearby villages (Urmalu and Chukdouman) came to Bey Alan and demanded ten liras and a ‘top’ [bolt] of cloth in consideration of which they would save that village from deportation. But it was evident that their real purpose was to spy out and see that these villagers got no word of what was happening at other points. They further demanded that one coppersmith and one blacksmith be given to their villages, and this was done. This was merely a blind.

On Wednesday, February 15, the men hiding in the forest nearby heard 5 or 6 rifle shots, and saw two houses burning in the village. They crept as near as they could and saw that there were at least 200 or 300 soldiers of these bands of Osman Agha in the village, and also a lot of Turkish women who had evidently come to carry off the plunder, which they were doing. All the cattle, as well as the household goods, were being taken off. The women and children of the village were not to be seen, which roused fears that they had been killed. The destruction continued all that day, till finally all the houses in both upper and lower quarters of the village had been burned except two. Out of about 175 women and children, and a few men hiding in cellars, only four persons escaped, and that as if by a miracle. Their story confirmed the worst fears of those hiding in the woods. All the women and children had been gathered into the two houses, with the exception of about fifteen girls of over sixteen years old, and the houses then burned over their heads, any who attempted to escape being shot down. One woman succeeded in escaping by feigning death in a valley. The wife of the man giving this report ran off as far as a garden in this valley, but was followed up by the Turks and shot there, while lying down to hide herself. The young girls were subjected to the most horrible treatment all night, and all butchered the next day. Some say that 5 or 6 were reserved for the harem of the pasha.

The other nine villages near Bey Alan had all received already the same treatment, and had been annihilated. Their names were:

- Mikro Tepe Keuy [Köy]

- Bozat

- Meghalo Tepe Keuy

- Kale Gennu

- Pazar Souyou [Bazar Suyu]

- Ghousers

- Yoma

- Kara Sar

- Demirji Keuy [Demirci Köy]

About fifty of the men were saved, having hidden in the woods before the slaughter began. They watched for the withdrawal of the Turkish troops who stayed there for several days. At last, after 23 days, the men came back and buried the corpses.

Deponent, at much risk to his life, succeeded in getting to Ordu, and later to Batum, and after spending some time in prison at the instigation of the Turkish Consul, finally escaped and came to Constantinople’.”

Source: National Archives, US State Department document 867.4016/59.8; quoted from: Shenk, R.: America’s Black Sea fleet: The U.S. Navy amidst war and revolution, 1919–1923. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2012